French economist Thomas Piketty will discuss his new research into the historical roots of economic inequality around the world.

Photo by Joel Saget

How political ideas keep economic inequality going

Thomas Piketty takes a long look at global history and ways to redistribute wealth

As the gulf between the haves and the have nots continues to widen, the roiling debate over economic inequality has become a political prime mover in the U.S. and across Europe. French economist Thomas Piketty’s 2013 landmark analysis of Western economic inequality, “Capital in the 21st Century,” became a must-read in both popular and academic circles. Now, he’s back with “Capital and Ideology” (Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 2020), a global look at the history of the problem, how institutions and ideologies reinforce it, and how it can be remedied.

Piketty will visit Harvard on Friday to give the Stanley Hoffmann Lecture on France and the World at the Minda de Gunzburg Center for European Studies (CES). He will return April 6 for a Weatherhead Initiative on Global History talk and give the annual Tanner Lectures on Human Values on April 15. The English version of “Capital and Ideology,” translated by Arthur Goldhammer, the distinguished book translator and longtime CES affiliate, is due out March 10.

Piketty, a professor at the School for Advanced Studies in the Social Sciences (EHESS) and the Paris School of Economics, spoke to the Gazette about his anxiously awaited new book.

Q&A

Thomas Piketty

GAZETTE: You write that inequality is not the result of economics or technological change, but is rooted in ideology and politics. How so and why is it important to understand its roots — how does that aid in its dismantling?

PIKETTY: What I do in this book is take a very long-run look at the inequality regime in a comparative perspective. I define “inequality regime” as the justification [used] for the structure of inequality and also the institutions — the legal system, the educational system, the fiscal system — that help sustain a certain level of equality or inequality in a given society. I look at the history of this inequality regime over a very long run, across many countries and regions of the world, and what I first observed is a lot of variation over time. You see very fast transformation, sometimes due to revolution, [like] the French Revolution. But also, Sweden used to be a very unequal country until the beginning of the 20th century. And then, following a very large social mobilization by trade unions and the Social Democratic party, Sweden became one of the most equal countries in history. You could say the U.S., after the Great Depression, also turned to a very progressive tax system and reduced its inequality enormously.

And so, in all these historical experiences, what’s very striking is the speed and the magnitude. If you had told people in Sweden in 1910 that the country was going to become a social democratic Sweden 20 years later, nobody would have believed it. The dominant groups always tend to be conservative and always tend to define the existing inequality as being natural, coming from some natural scheme or natural institutions or from rules that cannot be changed. But, in practice, what you see is something very different: The way inequality is organized can change very quickly. Sometimes it takes major shocks, including revolution and war, but it also happens very often in a peaceful manner like Sweden or the U.S.

So this is the story I tell in the book, and it’s important because I think it will be the same in the future. Nobody knows where change will come from — from an election, from social movement, the growing awareness of the climate crisis or other factors of change. But the idea that the current economic system will never change and we’ll just continue with business as usual forever is just not convincing at all, especially in light of the rich political history of inequality regimes that I put forward in this book.

“It’s everybody’s job and responsibility to take part in this conversation about changing the economic system.”

GAZETTE: You seem to have taken to heart some of the limitations of “Capital in the 21st Century.” One that you’ve frequently acknowledged is the last book’s Western-centric focus and what you’ve called its “black box” treatment of the political and ideological changes associated with inequality. How have you tried to rectify those shortcomings here?

PIKETTY: First, I show how the rise of inequality in Western societies was very much rooted in a system of world domination and of colonial domination and colonial appropriation. It’s a theme that was present a little bit, but was not very well developed. So now, I insist on the importance of slave societies and post-slavery colonial societies in the formation of modern inequality. It played a very big role, and in particular, the large wealth portfolio of European society in the 19th century and early 20th century came from colonial wealth and colonial appropriation. It also played a big role in this [private] ownership society in the 20th century. The international dimension and the colonial dimension of the inequality regime of the 19th century and early 20th century is very important in order to better understand the origin of the transformation that finally took place in the 20th century.

Also, the system of justification of inequality is also much more at the center of this book. The last part of this book is tied to the evolution of the electoral structure — who votes for the Democratic Party in the U.S., who votes for the Labour Party in Britain or for the Social Democratic Party in Germany or the Socialist Party in France. All of this changes [after] World War II. I show that these parties that were the parties of workers and had the highest electoral score among the lowest education group and the lowest income and wealth group, have actually become, over the past 40 or 50 years, the parties of the educated. I try to understand why and argue that this has to do with the ideology of these parties. The political platforms advocated by these parties have become less and less concerned with inequality and redistribution, or at least this is what I argue. This work is able to better go after the matter when it comes to the deep forces behind changes in inequality.

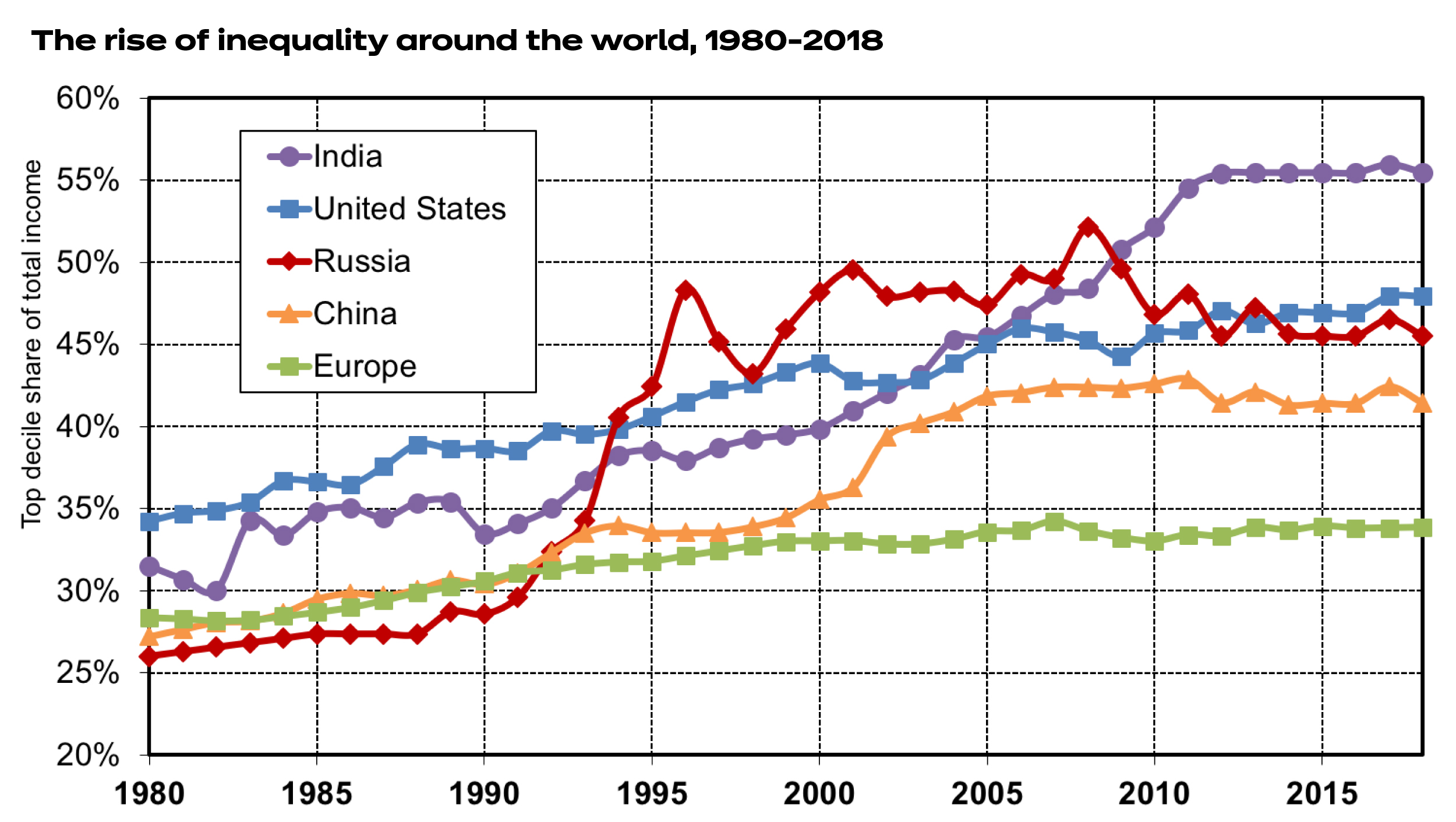

The share of the top decile (the 10 percent of highest earners) in total national income ranged from 26 to 34 percent in different parts of the world and from 34 to 56 percent in 2018. Inequality increased everywhere, but the size of the increase varied sharply from country to country, at all levels of development. For example, it was greater in the United States than in Europe (enlarged European Union, 540 millions inhabitants) and greater in India than in China.

Sources and series: see piketty.pse.ens.fr/ideology.et

GAZETTE: Much of current focus on inequality centers on the rise of right-wing populism and appeals to ethnic, religious, and national divisions. But you say the rise of elitism and the left’s failure to offer a persuasive counter-ideology to right-wing populism deserves more scrutiny. Can you elaborate?

PIKETTY: What I mean is that in the post-War period, in the ’50s and ’60s, the Democratic Party in the U.S. and social democratic parties in Europe were able to convince voters with lower education, lower income, lower wage[s] that they are the platform for them. That, in effect, what ties them together, despite their differences … is a platform of educational expansion, workers’ rights, Social Security, progressive taxation. [This] is what has made this coalition stick together. Then, what we see is that gradually over the past four decades, these parties have become the party of the educational elite. So while the right-wing parties and the center-right party are still the parties of the business elite or the high wealth elite … [W]e have moved from this class-based system to what I describe as a multi-elite system, where basically the educational elite votes for the Brahmin left and the wealthy elite votes for the merchant right or the business right. This rise of elitism, in effect, has left a lot of voters feeling abandoned [by] the main two parties, and I feel this has largely contributed to the rise of what is sometimes known as populism.

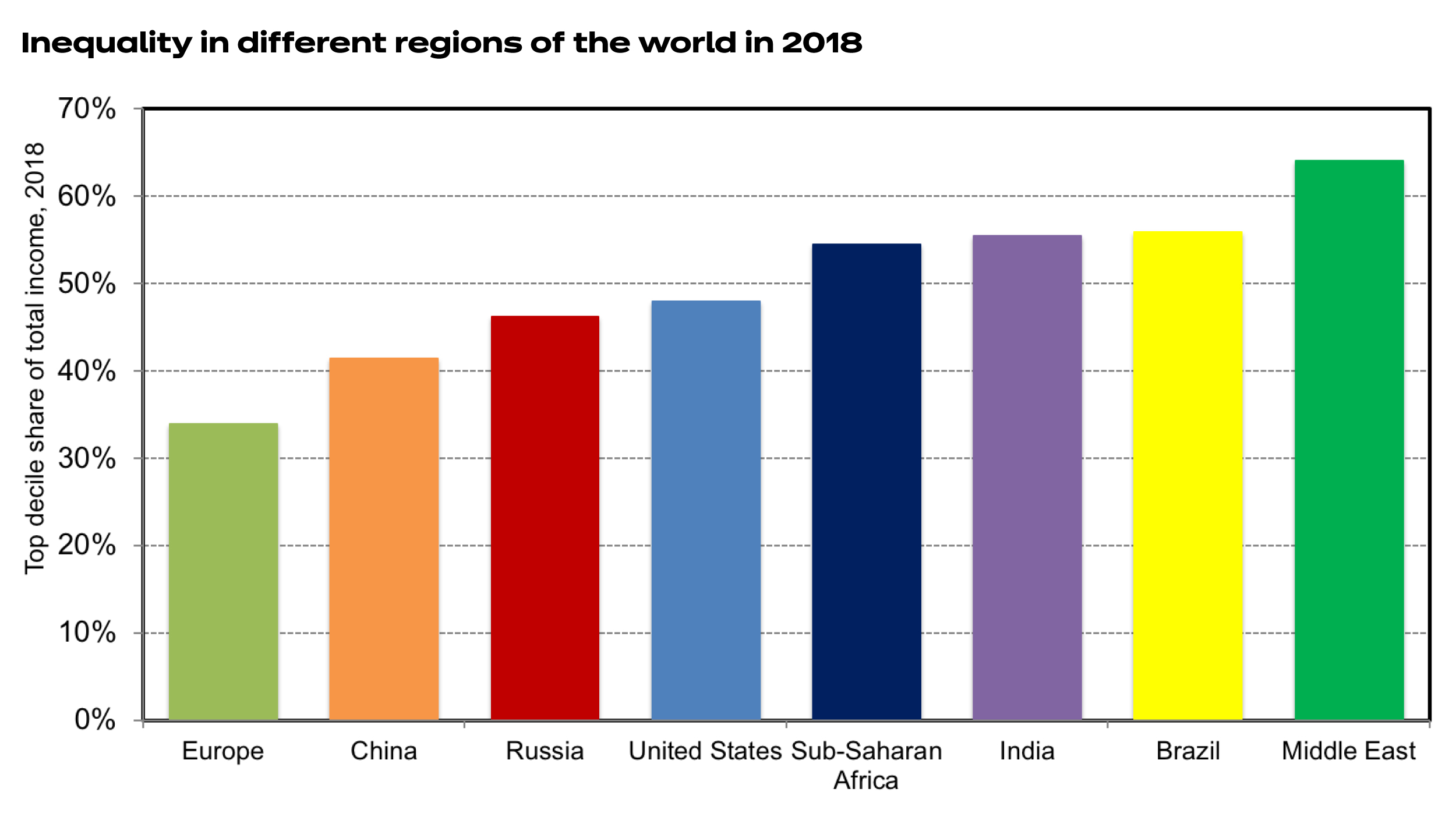

In 2018, the share of the top decile (the highest 10 percent of earners) in national income was 34 percent in Europe, 41 percent in China, 46 percent in Russia, 48 percent in the United States, 54 percent in sub-Saharan Africa, 55 percent in India, 56 percent in Brazil, and 64 percent in the Middle East.

Sources and series: see piketty.pse.ens.fr/ideology

GAZETTE: You propose a way forward that reinstitutes a progressive tax system that will fund something like a universal basic income. Broadly, what does that look like? How do you get the rich and powerful to give things up? And why was it important to you not just to document and analyze inequality, but to also offer a possible solution?

PIKETTY: It’s everybody’s job and responsibility to take part in this conversation about changing the economic system. I think it’s too easy for scholars and social scientists and economists and historians like myself … just to describe or to talk about history and not to take a stand in the present and in the future. So I’m trying to make an effort to deal with the future. People can either believe or come to their own conclusions from the historical material I present.

What do I feel has the most promise for the future? There are two main ideas, one is social federalism and the other is participatory socialism. Social federalism is a view that if you want to keep globalization going and you want to avoid this retreat to nationalism and the frontier of the nation-state that we see in a number of countries, you need to organize globalization in a more social way. If you want to have international treaties between European countries and Canada and the U.S. and Latin America and Africa, these treaties cannot simply be about free trade and free capital flow. They need to set some target in terms of equitable growth and equitable development. So, how much you want to tax large international corporations [and] high wealth/high income individuals? What kind of target do you want for carbon emissions? Free trade and free capital flows can be part of this new and more social international treaty that we need to organize globalization, but they can’t be the first chapter of this treaty. They must be put to the service of higher goals, goals about sustainable development and equitable development, and they must be regulated. Technically, it’s not so complicated. The issue is really not political and ideological. We’ve been accustomed for several decades to treaties without any explicit fiscal or social policy. This has to change.

Participatory socialism is the general objective of more “access” to education. Educational justice is very important in terms of access to higher education. Today there’s a lot of hyper criticism, not only in the U.S., but also in France and in Europe, that we don’t set quantifiable and verifiable targets in terms of how children [from] lower [income] groups [gain] access to higher education, what kind of funding [they] have for higher education. The other big dimension is circulation of property, so I talk about “inheritance for all.” The idea is to use a progressive tax on wealth in order to finance [a] capital transfer to every young adult at the age of 25. This transfer is in effect, 120,000 euros [about $134,000] per person, [which is] about the level of medium wealth today in France or in the U.S. That will very much transform the ability of children from poor families or middle-class families to create their own firms. Just having this kind of property puts you in a different position in life in general — what kind of jobs, what kind of wage, do I need to accept? It transforms the basic structure of power in society and that’s something very important. What I propose is not full equality; there will still be a lot of inequality. But this would make a big difference. The general idea is that not only the children of wealthy parents who have good ideas can create companies and participate in the economy. We need to rely on a much broader group of the population.

Interview has been edited for clarity and condensed for length.

Friday’s Stanley Hoffmann Lecture on France and the World will be viewable via livestream.