U.S. testing for COVID-19 has been plagued with problems, according to experts, who anticipate that Massachusetts will need 1.4 million tests.

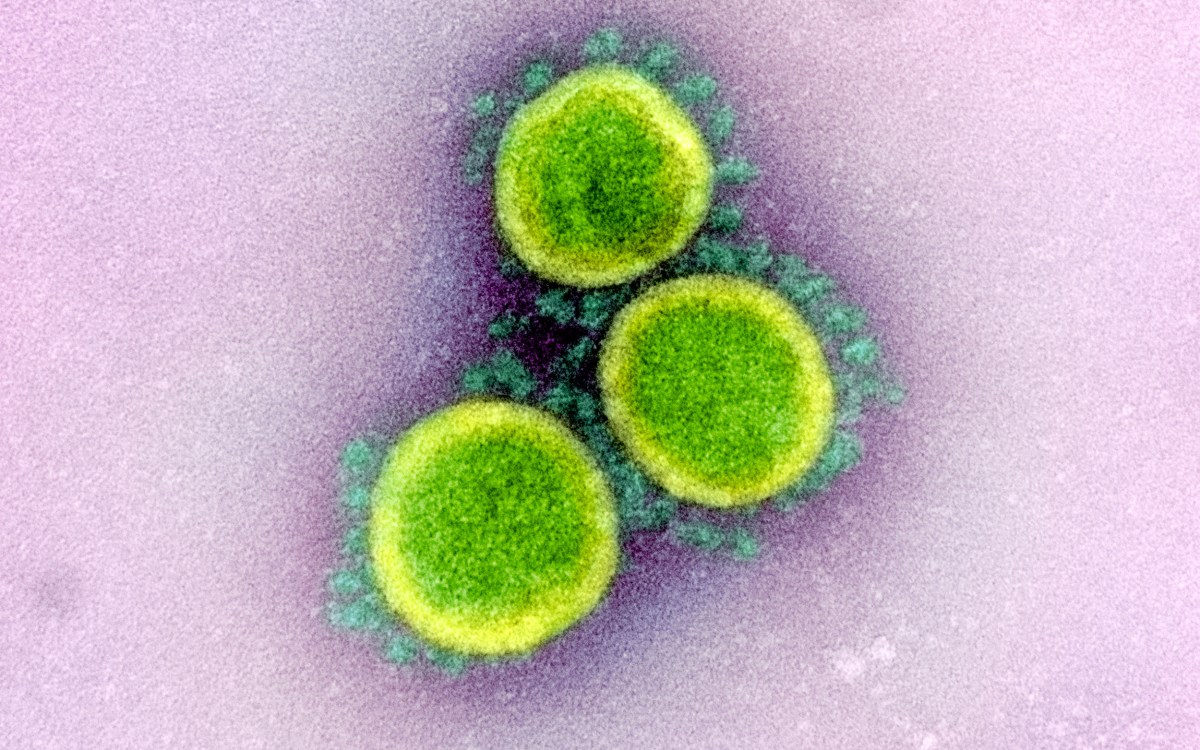

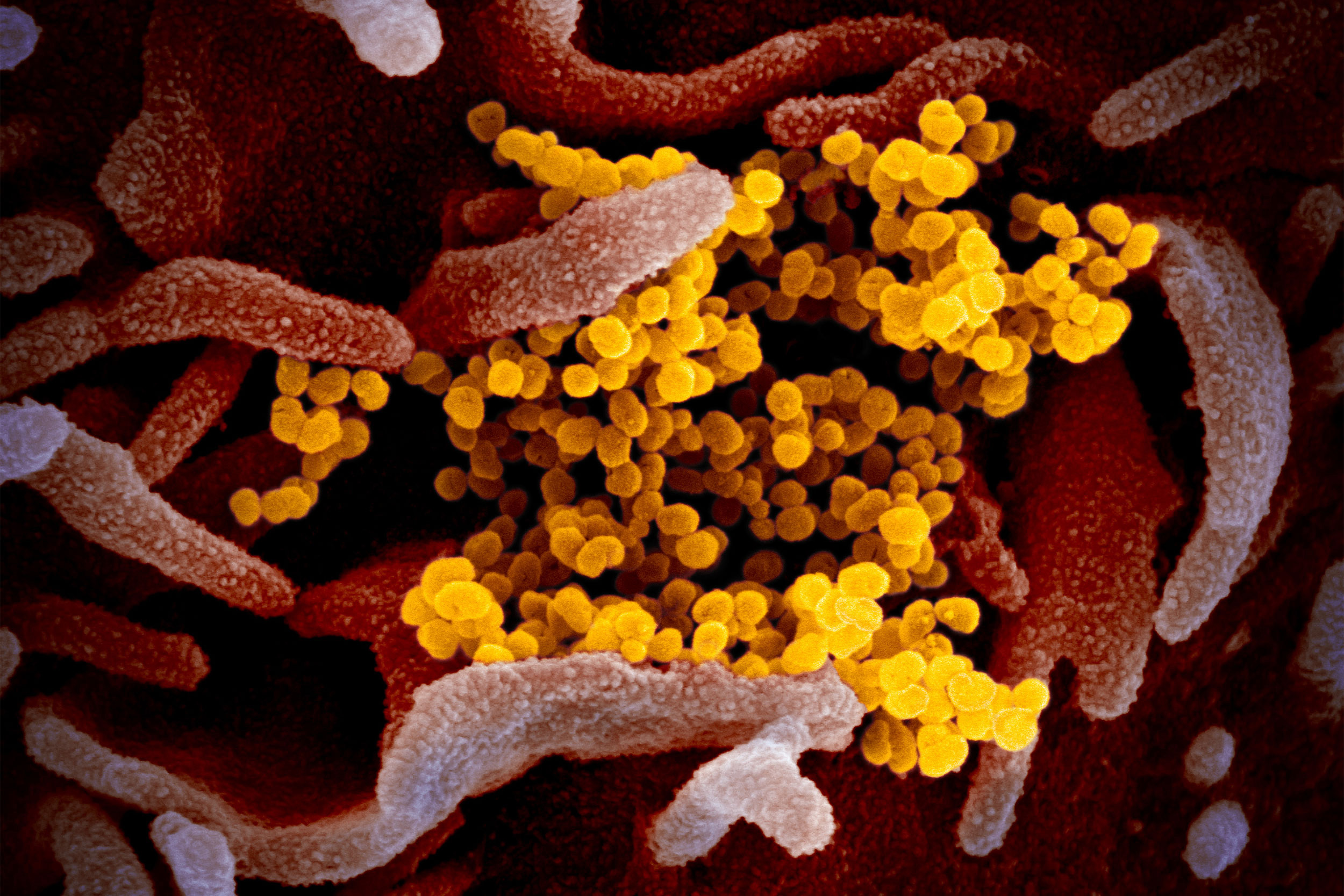

Credit: NIAID-RML

COVID test debacle: ‘We hoped it would go away before it reached us’

Harvard experts say Massachusetts may need 1.4 million tests

This is part of our Coronavirus Update series in which Harvard specialists in epidemiology, infectious disease, economics, politics, and other disciplines offer insights into what the latest developments in the COVID-19 outbreak may bring.

Massachusetts may ultimately need 1.4 million tests for COVID-19 and have to conduct tens of thousands a day, Harvard infectious disease experts said Friday, adding their voices to a nationwide chorus calling to increase dramatically the pace of testing across the country.

“This is a scale that’s not anywhere near where we’re at right now,” said Pardis Sabeti, professor of immunology and infectious diseases at the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health and a researcher at the Broad Institute of MIT and Harvard. Sabeti added that Americans have refused to learn preparedness lessons offered by Ebola, SARS, and other prior epidemics. “The fundamental fact is … that we don’t focus on preparedness; we focus on reaction. Every time, again and again, we wait. And there’s so many things that we could have in place so that we could move quickly.”

The anticipated rate of necessary testing is hundreds of times the level currently being done here. Massachusetts Gov. Charlie Baker said on Saturday that 475 people had been tested in the state. On Sunday, the state said 26 additional cases had been detected, bringing the total to 164.

Baker on Sunday took the additional steps of closing restaurants in the state to on site eating, banning meetings of more than 25, and closing schools through April 7.

Sabeti said her lab had working diagnostics back in January, within days of receiving the virus’s genome from Chinese researchers, so there’s no reason why every hospital shouldn’t have had diagnostic tests ready to go now. Instead, Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and other regulatory guidelines dictated that only state labs could do the testing.

“That was an incredible feat. They caught it early,” Sabeti said of Chinese researchers’ work on the virus. “We had an opportunity to be well ahead of the game.”

The rollout of testing has been plagued with problems. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s (CDC) initial test kits were found to be flawed by early February, forcing a scramble to develop and gain FDA approval for new kits. Since then, federal health officials agree, testing has been snarled in manufacturing problems and shortages of key chemicals, cotton swabs, and gloves, as well as red tape over allowing outside companies and academic labs to produce tests.

“Testing is the biggest problem that we’re facing.”

Peter Slavin, MGH

Over the last week, the Trump administration first promised, then walked back from promising tests for anyone who needs them. On Thursday, Anthony Fauci, director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, admitted to Congress that testing “is a failing. Let’s admit it.” On Friday, the FDA approved a test by Swiss drugmaker Roche that can provide results in three hours.

Peter Slavin, president of Harvard-affiliated Massachusetts General Hospital, offered some hope, saying that MGH and Brigham and Women’s Hospital have been approved for and begun testing in their own hospital-based labs, though the initial numbers are small compared to the need, about 130 daily between the two institutions.

More like this

South Korea, which the World Health Organization recently praised for its handling of the crisis, has tested about 4,000 people per million of its population, Slavin said. In the U.S., that level has been about 5 tests per million.

“Testing is the biggest problem that we’re facing,” Slavin said.

According to the World Health Organization, the global pandemic reached 153,000 cases in 143 countries Sunday, with 5,735 deaths. The U.S. reported 1,629 cases and 41 deaths.

Speakers said the problem in the U.S. is twofold. The U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s guidelines for who can be tested remain restrictive, but even if they’re loosened the test supply is so inadequate that hospitals will have to ration testing to only the most likely COVID-19 cases.

“There was a tsunami coming that we could see, and we hoped that it would go away before it reached us.”

Eric Rubin, Harvard Chan School

“We should ideally be doing tens of thousands of tests per day,” said Lindsey Baden, the Brigham’s director of clinical research and an associate professor at Harvard Medical School. “The criteria from the CDC made sense weeks ago, but I don’t think it makes sense currently, at what’s likely the transmission [rate today]. … We need to stand up testing for tens of thousands of people per day, and once we do that we’ll be in a very different place to be able to respond to this event.”

The comments came at the close of a roundtable event at the Medical School, hosted by HMS Dean George Daley and featuring U.S. Sen. Ed Markey. It brought together academic experts, health care leaders, and representatives of nurses, hospitals, and other key stakeholders.

During a news conference at the session’s close, Markey called on President Trump to declare a national emergency, which would free billions of dollars that could be used to both respond to the crisis and ease the economic pain felt by businesses and individuals in regions that have canceled major gatherings, closed schools, and otherwise interrupted lives and the commerce associated with them. Late in the afternoon Trump declared the pandemic an emergency, freeing up $50 billion in federal money to combat the virus.

“There was a tsunami coming that we could see,” said Eric Rubin, the Irene Heinz Given Professor of Immunology and Infectious Diseases at the Chan School and editor of the New England Journal of Medicine, “and we hoped that it would go away before it reached us.”