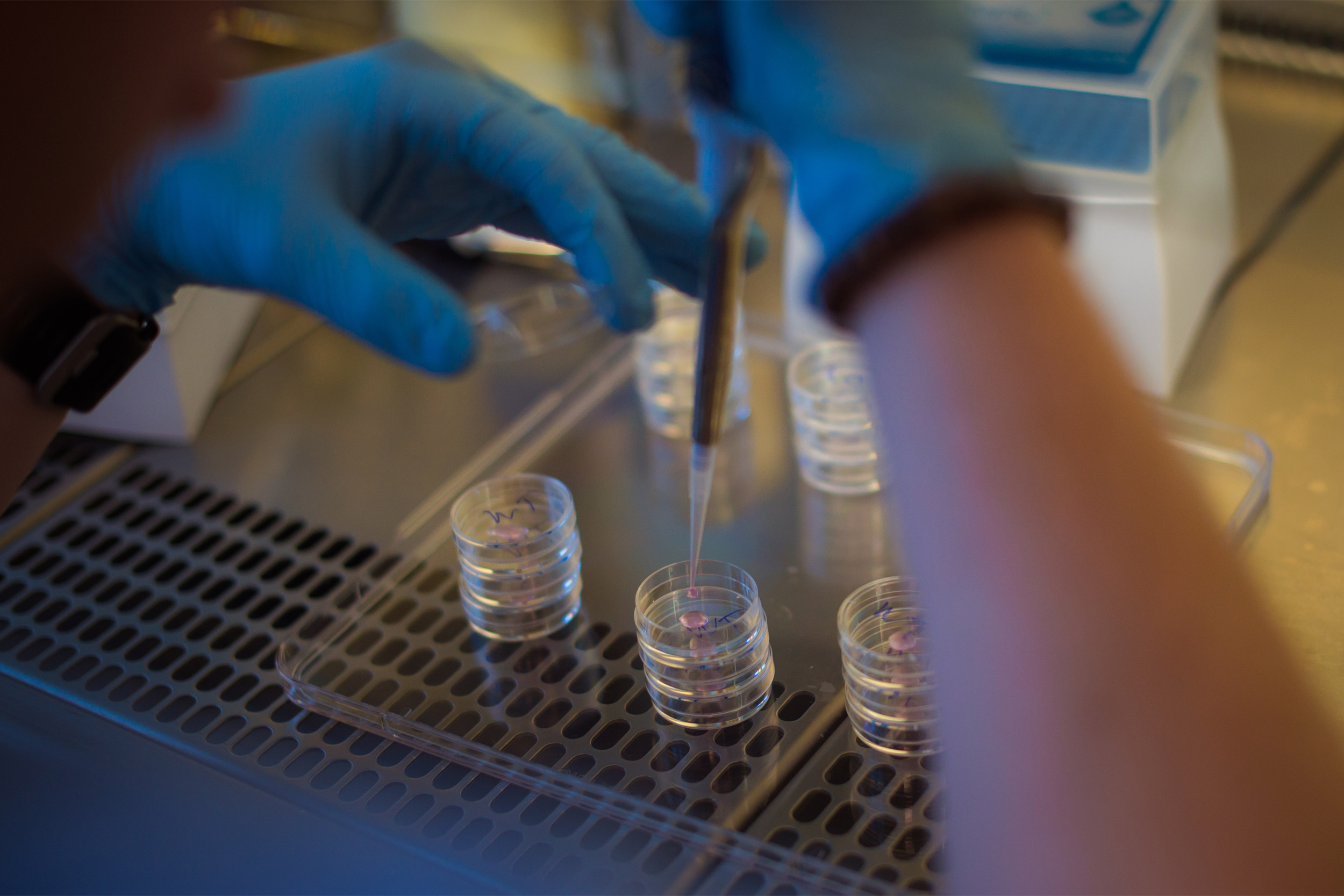

Photo by Gretchen Ertl

A ‘call to duty’ to battle a deadly global threat

New coronavirus collaboration joins Boston’s biomed community and researchers in China

This is part of our Coronavirus Update series, in which Harvard specialists in epidemiology, infectious disease, economics, politics, and other disciplines offer insights into what the latest developments in the COVID-19 outbreak may bring.

Researchers from around Boston are opening a new front against the deadly coronavirus by rallying the region’s biomedical science talent to develop better diagnostics, effective therapeutics, and potentially a vaccine.

The effort, announced Monday, will be mounted in collaboration with scientists at China’s Guangzhou Institute for Respiratory Health, and in particular the lab of Zhong Nanshan, head of the Chinese task force fighting the disease. Those involved said an important aspect of the new international collaboration is not only its work with Chinese colleagues but also its coordination of local labs: Boston-area researchers at Harvard, its affiliated hospitals, the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Boston University, area biotech companies, and others.

“We’re approaching this in a very different way than business-as-usual and trying to leverage the phenomenal biotech community here in Boston to work collaboratively and have an impact on this epidemic,” said Bruce Walker, director of the Ragon Institute of MGH, MIT and Harvard, and the Phillip T. and Susan M. Ragon Professor of Medicine at Harvard Medical School.

Alarm over the disease has risen sharply over the past week as the death toll has risen to more than 2,700, and confirmed cases top 80,000 and have spread to nearly three dozen nations, according to the World Health Organization. Global financial markets plummeted in the early part of the week on fears that the virus could result in an economic downturn.

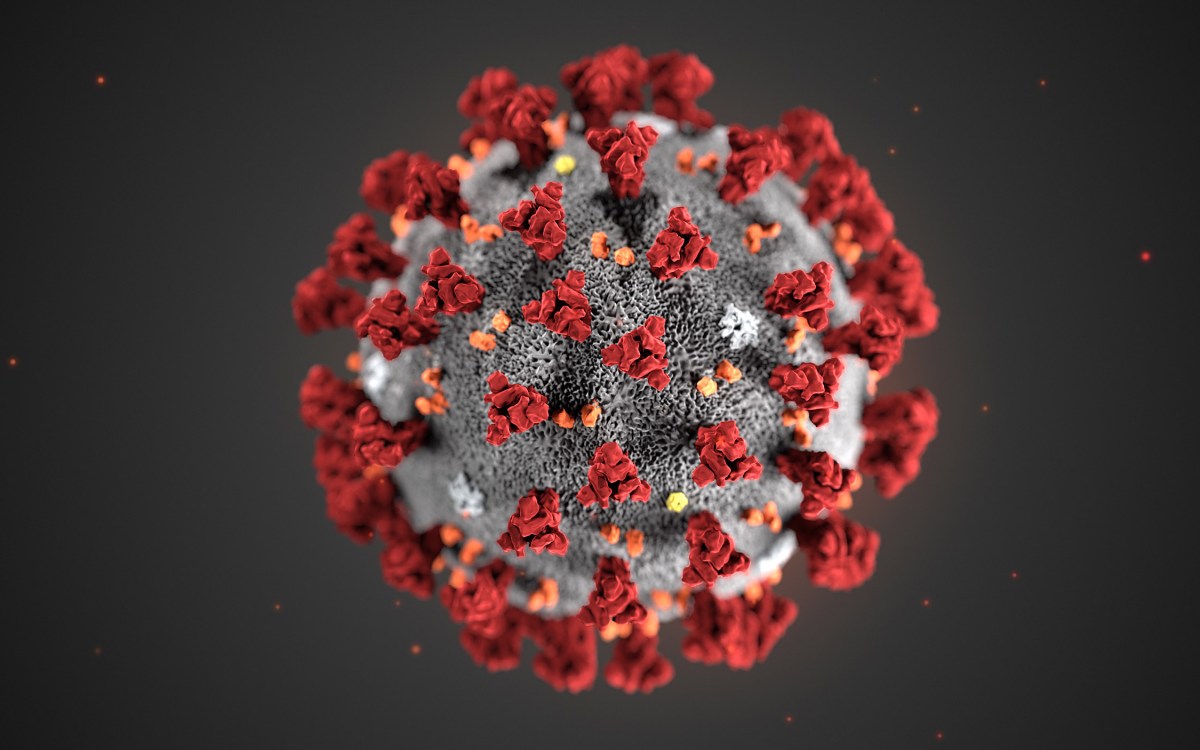

Walker said the Boston region is “unparalleled” in its biomedical prowess and, in a case like the global spread of the new coronavirus — SARS-CoV-2 and the disease it causes, called COVID-19 — ought to leverage the efforts of different labs working to better understand viral structure, how it spreads, how it sickens and kills those it infects, whether existing drugs and vaccines might be effective against it, and to develop new diagnostic tests, therapeutics to treat those in its grip, and vaccine candidates to one day stop its spread.

“The novel coronavirus and the disease that it causes have already resulted in a global health crisis, the repercussions of which are already reverberating across fields outside of health care. A crisis like this calls for scientific and humanitarian collaborations that transcend borders. For us, as scientists, this is nothing less than a call to duty,” said Harvard Medical School Dean George Q. Daley, who is heading the effort. “Harvard, its affiliated institutions, and our colleagues from academia and industry in Greater Boston have unique expertise. Our Chinese colleagues have dealt with the virus on the frontlines; they have unique access to samples, clinical and epidemiologic data, and first-hand observations. We each hold critical pieces to the puzzle.”

A key step in building the collaboration, funded over five years by $115 million from the China-based Evergrande Group, will occur Monday during a meeting of area researchers at Harvard Medical School. Walker said he expects about 80 researchers to attend. They’ll break into groups focused on different aspects of the problem to discuss what’s known and unknown, and what priorities should be adopted in the struggle to stop the contagion.

“We have to attack this with a sense of urgency and unprecedented collaboration,” Walker said, adding that the virus could one day have significant impacts in the Boston area. “Some of us in the room that day may die of this.”

Officials at the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention said they fully expect that the virus will spread in communities across the nation. “It’s not so much of a question of if this will happen in this country anymore but a question of when this will happen,” Nancy Messonnier, director of the National Center for Immunization and Respiratory Diseases, told The New York Times.

“A crisis like this calls for scientific and humanitarian collaborations that transcend borders.”

George Q. Daley, Harvard Medical School

The new virus initially spread rapidly in China and has infected 77,780 people, with 2,666 dead as of Feb. 25, WHO reported. The number of new cases has been declining in China even as the relative handful of isolated cases internationally have grown into new outbreaks in South Korea, Italy, and Iran. Outside of China, there have been more than 2,400 cases and 34 deaths in 33 countries.

Epidemiologists, such as Marc Lipsitch, director of the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health’s Center for Communicable Disease Dynamics, say they expect the virus to eventually be widespread globally, driven in part by the large number of mild or asymptomatic cases that make it hard to detect.

Dan Barouch, professor of medicine at Harvard Medical School, Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, and the Ragon Institute of MGH, MIT, and Harvard, said his group began work on a vaccine as soon as the virus’ DNA sequence was released publicly on Jan. 10 and has been pushing toward the development and testing of candidate vaccines.

“Collaboration is critical for the development of a coronavirus vaccine, because no single group has all the necessary expertise, and open sharing of data and reagents will greatly accelerate the field,” said Barouch, who has also worked on HIV and Zika vaccines. “It is important for multiple vaccine efforts to go forward in parallel, because it is not yet known which vaccine candidates will be safest and most effective and also can be manufactured and deployed at the scale to end a global epidemic.”

In addition to sharing knowledge with colleagues in China, Boston-area scientists hope to access samples from Chinese patients, an important scientific resource currently in short supply, according to David Knipe, Higgins Professor and head of the program in virology at HMS’ Department of Microbiology.

More like this

Knipe, who has conducted work on the replication and latency of the herpes simplex virus and has a candidate vaccine for genital herpes in clinical trials, said although knowledge is lacking on many characteristics of the virus, efforts will focus immediately on steps that can help patients as soon as possible. Those efforts will likely include new and better diagnostic tests, screening existing antiviral drugs to see whether any can be an effective therapy against the virus, and finding a vaccine as quickly as possible.

Knipe said his own lab will probably focus on exploring the host immune response at a cellular level and the role inflammation plays in severe illness.

Mark Namchuk, director of HMS’ newly formed Therapeutics Initiative, said a thorough understanding of the virus, its fundamental biology, and its effect on patients is needed to guide efforts to understand which treatments may be effective.

“This is something that we have to take very seriously and do what can be done medically, scientifically,” Namchuk said, adding that though the coronavirus’ impact so far has largely been in China, it’s important to prepare for its broader spread. “Morally, we have to prepare to respond to this wherever it is.”

Jonathan Abraham, assistant professor of microbiology in HMS’ Department of Microbiology, said even though the need for rapid progress remains urgent, the pace of the response has already been unprecedented. His lab studies how viruses bind to cells to infect them and the antibodies generated by patients who have survived infection.

Unfortunately, Abraham said, antibodies against SARS won’t necessarily be effective against the new virus, so researchers are looking for strategies to not only address the new virus, but also related viruses that may emerge in the future.

“I think it’s critical that’s being learned here is that it’s important to carry out this sort of highly collaborative research on these important pathogens before they emerge,” Abraham said, “because we can use the information we learn from related viruses to help fight off infection by the new viruses when they emerge.”