Former President Barack Obama is pictured at the beginning of his presidency in January 2009 (left) and at the end, during President Donald Trump’s inauguration eight years later. Harvard researchers, for the first time, have discovered how stress turns hair gray.

AP file photos

Feel like kids, spouse, work giving you gray hair? They may be

New findings involving nervous system and stem cells suggest just how stress may trigger the change

History is replete with anecdotes, more and less verified, of individuals whose hair turned white or gray due to stress.

Marie Antoinette’s hair was said to have turned the color of snow overnight while she awaited the guillotine during the French Revolution. The late Sen. John McCain, a Navy pilot during the Vietnam War, suffered multiple serious injuries when his plane crashed in North Vietnam and during beatings while a prisoner of war — and lost color in his hair.

Now, for the first time, a group of Harvard researchers have discovered why that happens: Stress activates nerves that are part of the fight-or-flight response, which in turn causes permanent damage to pigment-regenerating stem cells in hair follicles. Their study on graying has just been published in Nature, and the results offer new insights into how stress can impact the body.

“Everyone has an anecdote to share about how stress affects their body, particularly in their skin and hair — the only tissues we can see from the outside,” said senior author Ya-Chieh Hsu, the Alvin and Esta Star Associate Professor of Stem Cell and Regenerative Biology at Harvard. “We wanted to understand if this connection is true, and if so, how stress leads to changes in diverse tissues. Hair pigmentation is such an accessible and tractable system to start with — and besides, we were genuinely curious to see if stress indeed leads to hair graying.”

Because stress affects the whole body, researchers first had to narrow down which specific systems were involved. The team first hypothesized that stress causes an immune attack on pigment-producing cells. However, when mice lacking immune cells still showed hair graying, researchers turned to the hormone cortisol. Once again, they found a dead end.

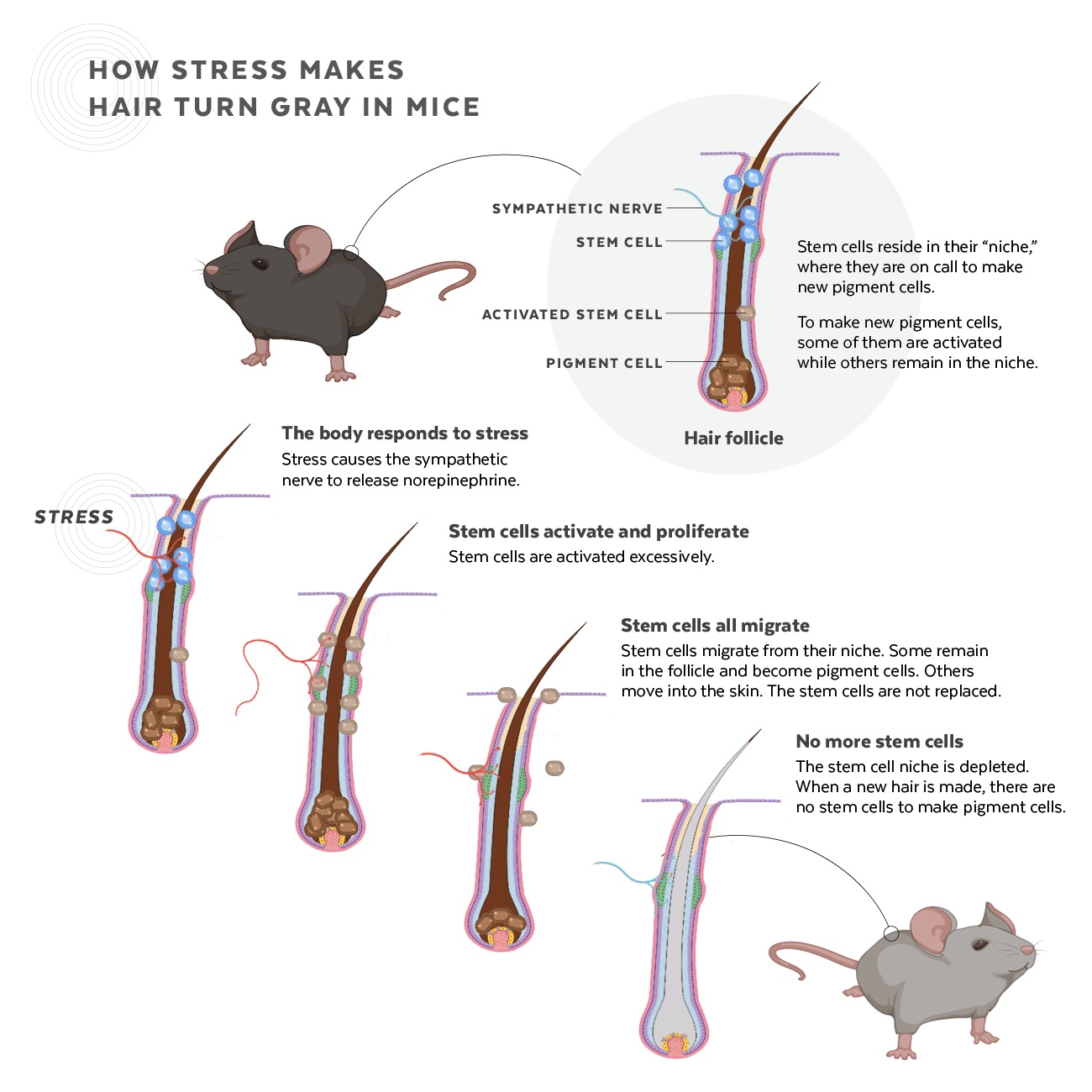

Infographic depicting how stem cells are depleted in response to stress, causing hair to turn gray in mice.

Judy Blomquist/Harvard University

“Stress always elevates levels of the hormone cortisol in the body, so we thought that cortisol might play a role,” Hsu said. “But surprisingly, when we removed the adrenal gland from the mice so that they couldn’t produce cortisol-like hormones, their hair still turned gray under stress.”

After eliminating different possibilities, researchers honed in on the sympathetic nerve system, which is responsible for the body’s fight-or-flight response.

Sympathetic nerves branch out into each hair follicle on the skin. The researchers found that stress causes these nerves to release the chemical norepinephrine, which gets taken up by nearby pigment-regenerating stem cells.

In the hair follicle, certain stem cells act as reservoirs of pigment-producing cells. When hair regenerates, some of the stem cells convert into pigment-producing cells that color the hair.

Researchers found that the norepinephrine from sympathetic nerves causes the stem cells to activate excessively. The stem cells all convert into pigment-producing cells, prematurely depleting the reservoir.

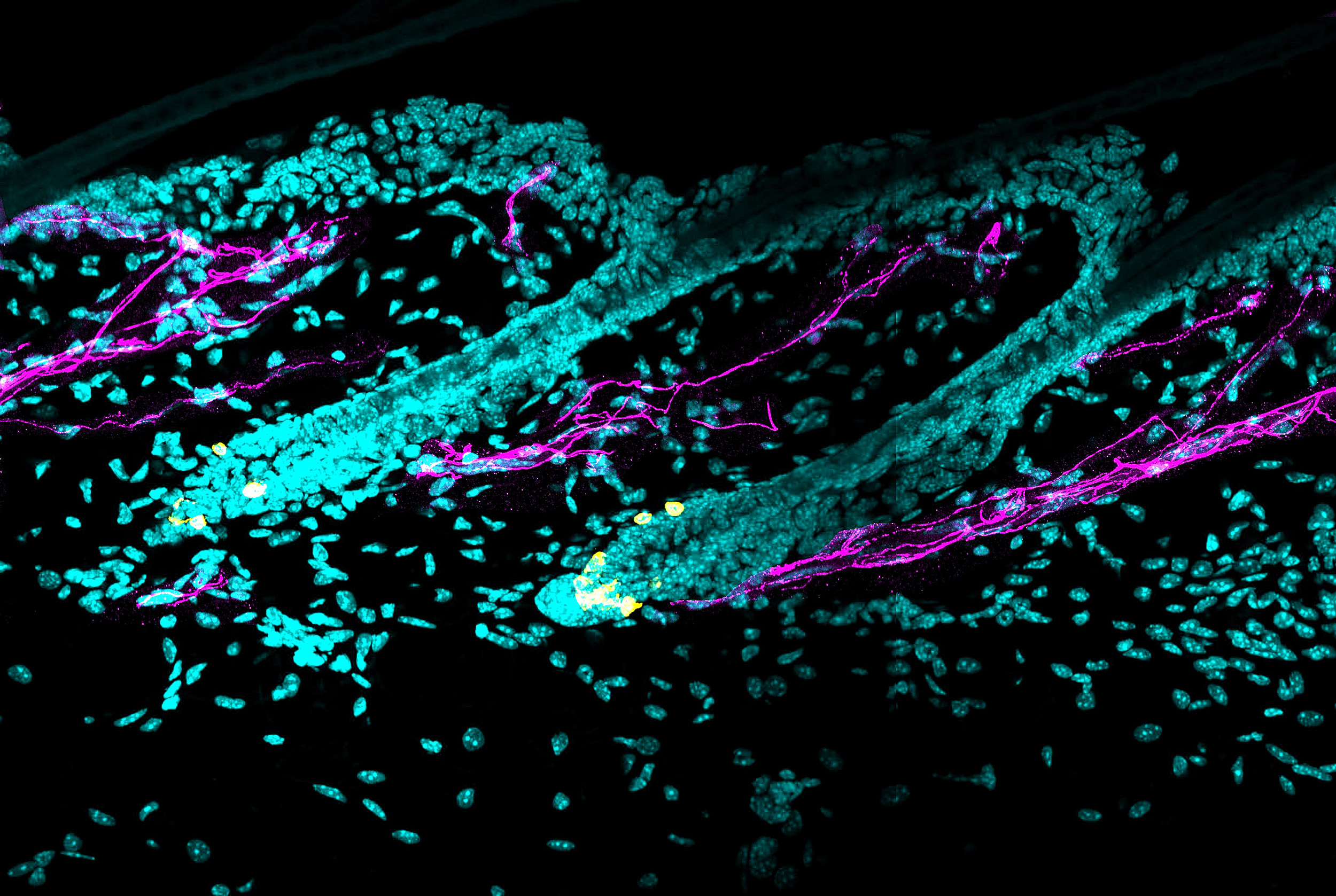

Elaborate sympathetic innervation (magenta) around melanocyte stem cells (yellow). Acute stress induces hyperactivation of the sympathetic nervous system to release large amounts of the neurotransmitter norepinephrine. Norepinephrine drives rapid depletion of melanocyte stem cells and hair graying.

Hsu Laboratory, Harvard University

“When we started to study this, I expected that stress was bad for the body — but the detrimental impact of stress that we discovered was beyond what I imagined,” Hsu said. “After just a few days, all of the pigment-regenerating stem cells were lost. Once they’re gone, you can’t regenerate pigments anymore. The damage is permanent.”

The finding underscores the negative side effects of an otherwise protective evolutionary response, the reseachers said.

“Acute stress, particularly the fight-or-flight response, has been traditionally viewed to be beneficial for an animal’s survival. But in this case, acute stress causes permanent depletion of stem cells,” said postdoctoral fellow Bing Zhang, lead author of the study.

To connect stress with hair graying, the researchers started with a whole-body response and progressively zoomed in on individual organ systems, cell-to-cell interaction, and, eventually, all the way down to molecular dynamics. The process required a variety of research tools along the way, including methods of manipulating organs, nerves, and cell receptors.

“To go from the highest level to the smallest detail, we collaborated with many scientists across a wide range of disciplines, using a combination of different approaches to solve a very fundamental biological question,” Zhang said.

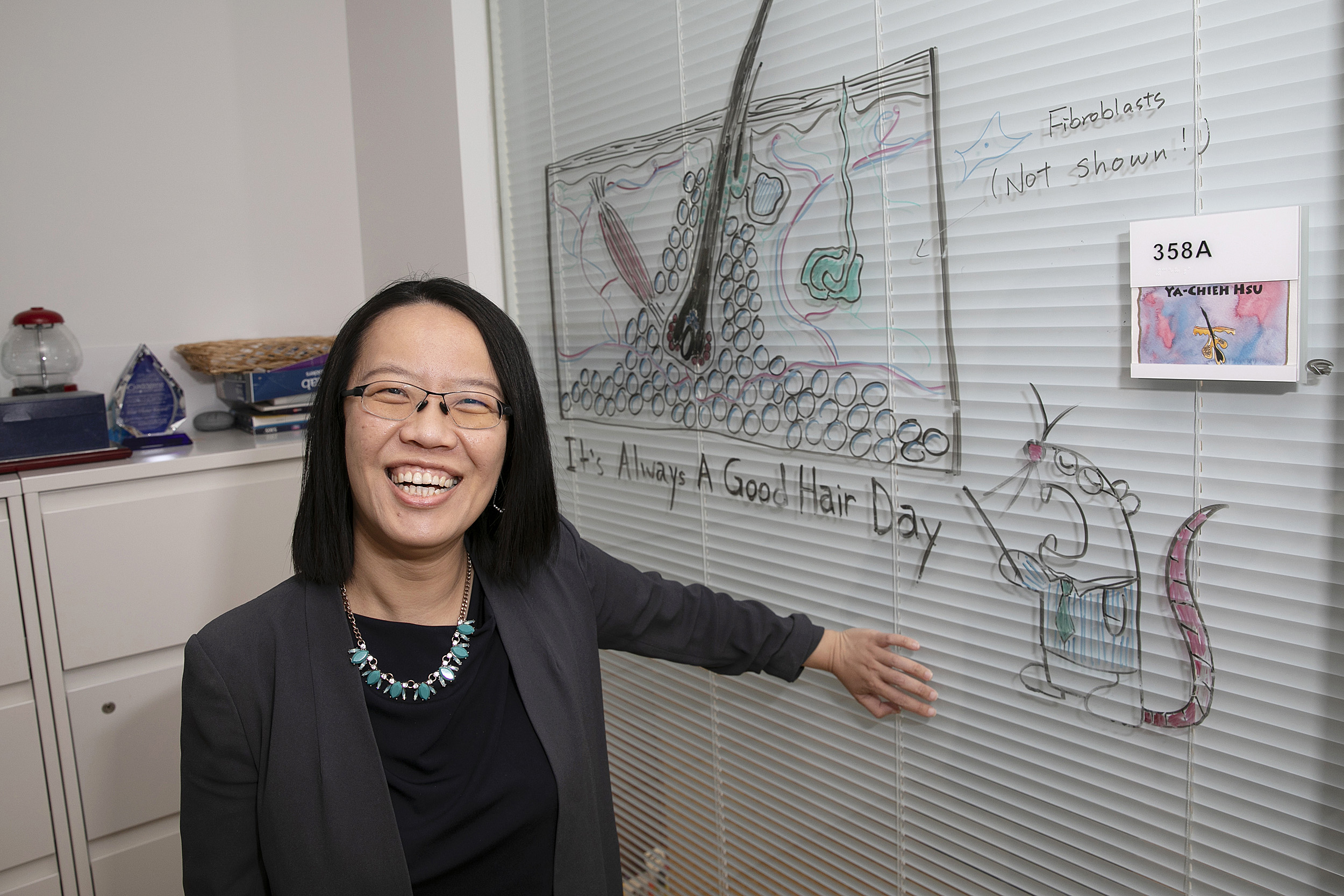

Senior author Ya-Chieh Hsu shows off a diagram of a hair follicle — complete with a helpful test mouse.

Jon Chase/Harvard Staff Photographer

The collaborators included Isaac Chiu, assistant professor of immunology at Harvard Medical School, who studies the interplay between nervous and immune systems.

“We know that peripheral neurons powerfully regulate organ function, blood vessels, and immunity, but less is known about how they regulate stem cells,” Chiu said. “With this study, we now know that neurons can control stem cells and their function, and can explain how they interact at the cellular and molecular levels to link stress with hair graying.”

The findings can help illuminate the broader effects of stress on various organs and tissues. This understanding will pave the way for new studies that seek to modify or block the damaging effects of stress. Harvard’s Office of Technology Development has filed a provisional patent application on the lab’s findings and is engaging prospective commercial partners who may be interested in clinical and cosmetic applications.

“By understanding precisely how stress affects stem cells that regenerate pigment, we’ve laid the groundwork for understanding how stress affects other tissues and organs in the body,” Hsu said. “Understanding how our tissues change under stress is the first critical step toward eventual treatment that can halt or revert the detrimental impact of stress. We still have a lot to learn in this area.”

The study was supported by the Smith Family Foundation Odyssey Award, the Pew Charitable Trusts, Harvard Stem Cell Institute, Harvard/MIT Basic Neuroscience Grants Program, Harvard FAS and HMS Dean’s Award, American Cancer Society, NIH, the Charles A. King Trust Postdoctoral Fellowship Program, and an HSCI junior faculty grant.