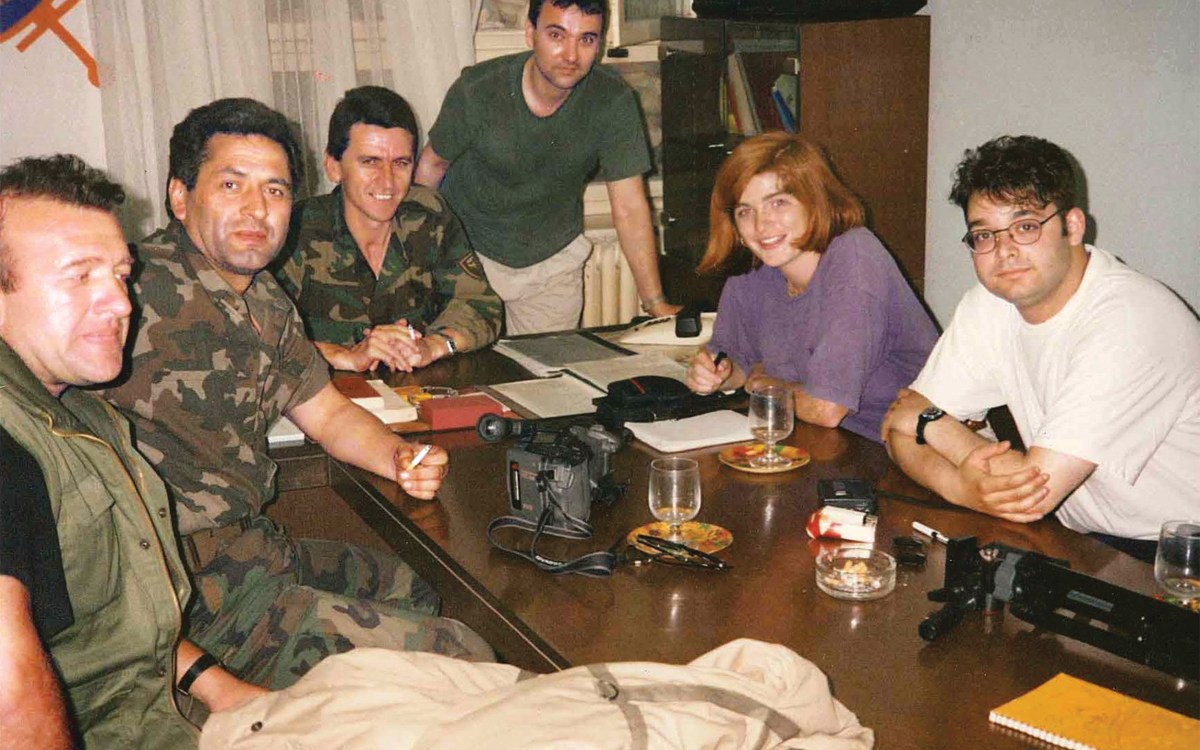

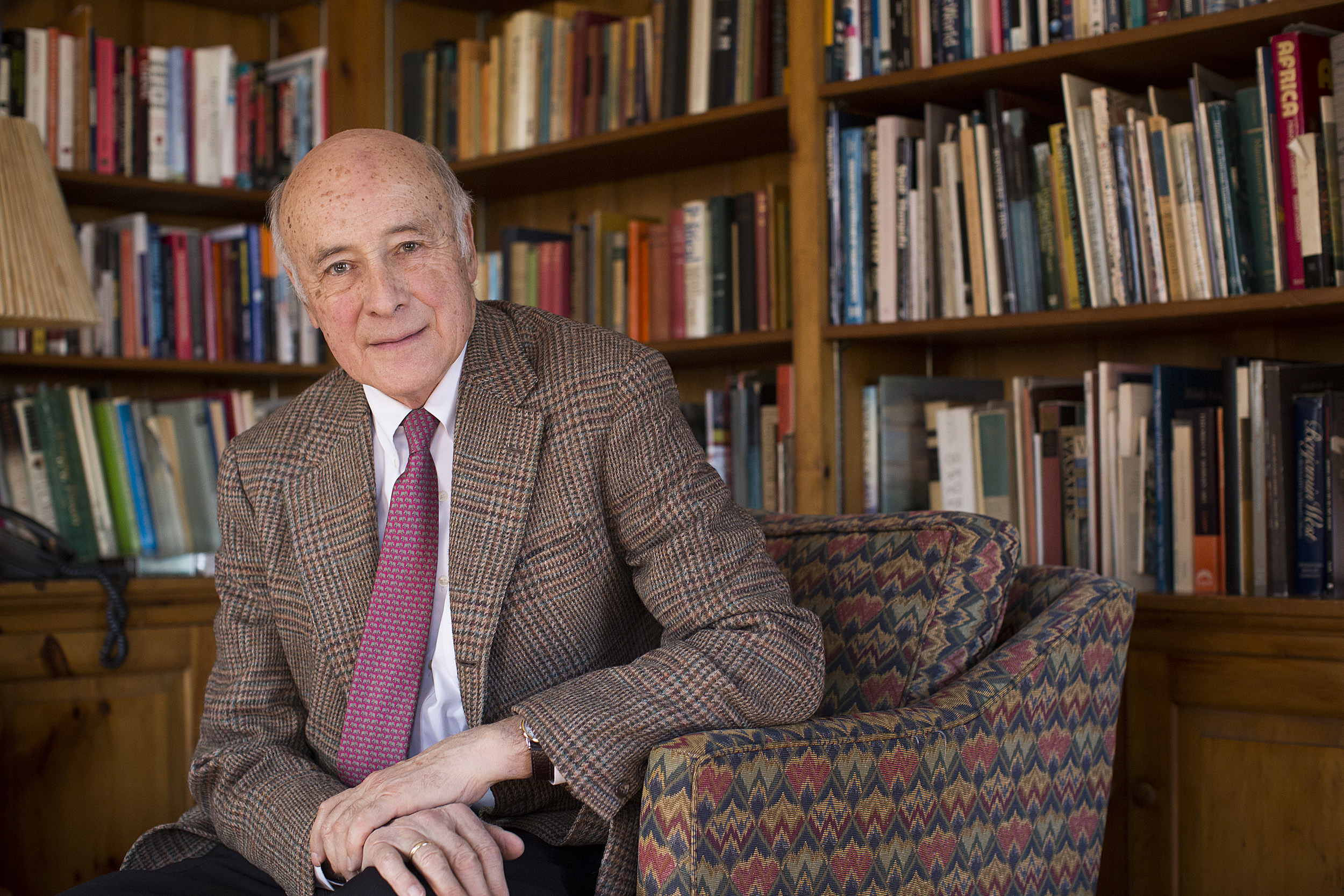

Joseph S. Nye Jr.’s new book explores questions like, “Should presidents ever tell lies? To what extent should they risk American lives?”

Stephanie Mitchell/Harvard file photo

What makes for a moral foreign policy?

Joseph Nye’s new book rates the efforts of presidents from FDR to Trump

As his trial begins in the U.S. Senate, the impeachment of President Trump is, at its heart, a question about ethics. Was it proper for the president to withhold U.S. military aid to a strategic foreign ally to leverage its cooperation in an effort that could undercut a political rival? In a new book, “Do Morals Matter? Presidents and Foreign Policy from FDR to Trump,” Joseph S. Nye Jr., University Distinguished Service Professor Emeritus at Harvard Kennedy School (HKS), examines the role that ethics played in the foreign policies of every U.S. president since World War II. In evaluating each on the moral soundness of their intentions, their results, and the means they used to achieve those results, Nye makes a case for the enduring relevance of American exceptionalism in the 21st century.

Q&A

Joseph S. Nye Jr.

GAZETTE: What prompted your interest in looking at foreign policy through a moral lens?

NYE: I used to teach a course here at the Kennedy School on ethics and foreign policy and so it has been on my mind. But obviously, the Trump administration has brought a lot of that to the fore in terms of the questions of: Should presidents ever tell lies? To what extent should they risk American lives? And to what extent should they take into account human rights in other countries? These are issues which have become a lot more salient as a result of some of the controversial decisions of the Trump administration.

There’s a big difference between the national interest and the personal and political interest of a president. The two sometimes get blurred, but this [Ukraine situation] seems to be a clearer differentiation than we’ve seen in cases in the past. To give you an example, Richard Nixon knew that he wanted to get out of Vietnam, but he also felt that he couldn’t get out too quickly because it would be damaging for American credibility. So they aimed to get what they called a “decent interval” between when the American troops would leave and when the South Vietnamese government would collapse. They thought it would be about two years. He spent 20,000 American lives to create a decent interval. It was partly his political interest to not be the man who lost Vietnam immediately. But it was partially a national interest to keep the credibility of U.S. guarantees, to make sure that it wasn’t too precipitous a defeat. So how much of that was personal, how much of it was national interest? That’s a hard one to parse. On the other hand, what we’re seeing in this Ukraine case, it’s pretty hard to see a national interest there.

“Americans want a certain amount of idealism and value in foreign policy. They also want to have their security protected and their prosperity advanced, and so a president is always balancing those two.”

GAZETTE: What is an ethical foreign policy and how can it be assessed in an objective way?

NYE: Sometimes people say if you have good intentions, that’s all that counts. Well, no. I argue that a moral foreign policy, like many moral decisions related to policy, have to combine three dimensions: the intentions, the means that are used, and the consequences. Balancing those three dimensions is what gives you an assessment of whether the policy was moral or not. But it’s not enough just to say, intentions were good, and it’s not enough to say it worked all right so therefore it’s good. You need to think of how you did it, as well — the means that were used.

GAZETTE: Modern presidents are generally thought to be firmly entrenched in just one of two foreign-policy camps, a Wilsonian liberalism or Machiavellian pragmatism. What did you find when you examined their track records closely?

NYE: What we find is, in practice, presidents draw from both. Americans want a certain amount of idealism and value in foreign policy. They also want to have their security protected and their prosperity advanced, and so a president is always balancing those two. Very few are totally cynical and pay no attention to values; very few can pay attention just to values.

GAZETTE: Presidents always have to make very difficult decisions that people will question and disagree with. Very few, if any, of those decisions have outcomes that satisfy everyone, whether it’s Nixon’s withdrawal from Vietnam or Trump’s response to the Jamal Khashoggi murder. In the Khashoggi case Trump decided that punishing Saudi Arabia was not worth the economic and political risks even as critics said it’s immoral for the U.S. not to have done so. Isn’t the definition often in the eye of the beholder?

NYE: There are always going to be trade-offs like that. Trump’s not the first to face those. People sometimes complained that Jimmy Carter paid too much attention to human rights. People are now complaining that Trump pays not enough attention. But those trade-offs are inevitable. Nixon and [Henry] Kissinger took a very strong view that nuclear arms control and détente with the Soviet Union took priority over getting Jews out of the Soviet Union. Sen. Henry Jackson took the opposite view and tried to torpedo détente. He said that Nixon and Kissinger were not doing enough for human rights. Kissinger’s alleged to have said at one point, “There are no human rights among the incinerated.” So you can have differences about how much human rights or values you want in your definition of a national interest.

GAZETTE: You grade each president on how they performed under the circumstances they faced and with the priorities they tried to advance. But is it fair to compare presidents to each other given those vast differences?

NYE: There’s always a certain arbitrariness. This is why I talk about contextual intelligence, which is, how good of a job did they do at trying to understand the context? The context can be very different in different circumstances. Take Harry Truman: When he became president in 1945, he dropped the atomic bomb on Hiroshima and Nagasaki, and many people faulted him for that. The practice of killing large numbers of civilians by bombing cities was widespread. In that context, it would have been quite extraordinary for Truman to have refused to drop the bomb. Doesn’t mean it was right or wrong that he did it. But it just means that the context was such that it was moving very heavily in a given direction. What’s interesting is that five years later, when Truman and the United States were losing the war in Korea, Gen. [Douglas] MacArthur said to him, “We’re losing. The only way I can win this is that you allow me to drop 25 to 50 atomic bombs on Chinese cities.” And Truman said “No, I’m not going to kill any women and children.” By then, he had learned a lot about what atomic weapons really were, which wasn’t well understood in ’45, and he also had a sense that if you open this Pandora’s box, it was going to spread. And so, the man who dropped the bomb on Hiroshima refused to drop it to save himself in the Korean War. That’s an example of a changed context, same person.

GAZETTE: Could we pluck someone from 1989 and drop them into 1945 and expect them to do a similar job?

NYE: You could in some sense. An interesting case is George H.W. Bush, who in 1989 responded extremely well to the collapse of the Berlin Wall. People said, “We should be declaring this as a great victory for the West.” And Bush said, “I’m not gonna dance on the Wall and make it more difficult for Gorbachev to do the things he needs to do to wind down the Cold War.” That showed an extraordinary amount of restraint. Franklin Roosevelt also used restraint in many cases as we began to work our way up to World War II. He knew that if he pushed American opinion too hard, too fast, he might lose the capacity to do what he needed to do to defeat Hitler. And he also made compromises with Stalin, who was a nasty dictator, because he felt that Hitler was even a greater threat. So presidents are making decisions and trade-offs. I think George H.W. Bush, who ranks very high by various scales, would have made the same types of decisions if he was in Roosevelt’s seat, and I suspect Roosevelt might have made similar decisions if he and Bush traded places.

GAZETTE: FDR, who was commander in chief of the U.S. armed forces that won the greatest global conflict in human history, gets fairly mixed marks. And President Nixon, who’s often lauded for his foreign policy achievements, particularly with China, scores pretty poorly. Were you surprised by any of the findings?

NYE: One of the personal surprises was how well George H.W. Bush did. As a personal note: I had worked in 1988 on the [Michael] Dukakis campaign and had done my best, obviously inadequately, to prevent George H.W. Bush from becoming president. And lo and behold, 32 years later, when I’m writing this book, I find he comes out pretty close to the top of the pile.

“A moral foreign policy … [has] to combine three dimensions: the intentions, the means that are used, and the consequences.”

GAZETTE: President Reagan gets a decent score from you.

NYE: Yeah. He’s in the middle rank and that too surprised me because I was more critical of him at the time. Many people, when Gorbachev first came to power in ’85, didn’t trust Gorbachev, didn’t see this as a possible way to wind down the Cold War. And Reagan was out in front of his fellow hawks in saying, “I can deal with this person.” And he did. When people think back on Reagan, they forget that he was not only the spokesman of business groups and leader of the right wing of the Republican Party, he’d also been the head of the actors union in Hollywood. They forget he also was able to perceive an opportunity to bargain and to find the compromises that were necessary. If you ask: Did Reagan end the Cold War? No. The biggest share of credit goes to Gorbachev. But Reagan had the sense to see that opportunity, see the moment, and to bargain.

GAZETTE: In the 21st century, with the rise of China and as the West seems to be drifting away from the post-World War II liberal world order, can we still hold on to the idea of a moral foreign policy, which is embedded in the notion of American exceptionalism?

NYE: I don’t think you can recreate the post-1945 situation. We’re still the largest country, but we don’t have this degree of preeminence that we had in the past, and it would be a mistake for us to try to recreate that degree of dominance or control. But you can say that there’s certain things where, if the largest country doesn’t take the lead in producing global public goods, nobody can. If we act as a free rider, nobody else will produce these. Take something like climate change, which is going to affect all of us. Cooperating with others and taking the lead is going to be essential. Or with international financial stability, where the dollar still is, by far, the dominant reserve currency in the world. If we don’t take the lead in terms of international financial stability and you have an international financial system which is wracked by crises, everybody suffers. Or developing rules for the global commons in cyberspace. If we don’t help to take the lead on this, it’s not going to get done. So we can have an interest as the largest country — not in dominating and controlling, because we can’t, but in trying to form coalitions of the willing, trying to develop alliances, trying to put together institutional frameworks which can provide these global public goods. And if we retreat from that broad definition of the national interest to a narrow, transactional one, then we will have sold ourselves short, as well as the rest of the world.

This interview has been condensed for length and edited for clarity.

| President | Moral vision | Prudence | Use of force | Liberal concerns | Fiduciary | Cosmopolitan | Educational |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Franklin D. Roosevelt | |||||||

| Harry S. Truman | |||||||

| Dwight D. Eisenhower | |||||||

| John F. Kennedy | |||||||

| Lyndon B. Johnson | |||||||

| Richard M. Nixon | |||||||

| Gerald Ford | |||||||

| Jimmy Carter | |||||||

| Ronald Reagan | |||||||

| George H.W. Bush | |||||||

| Bill Clinton | |||||||

| George W. Bush | |||||||

| Barack Obama | |||||||

| Donald J. Trump |

Key: Good | Mixed | Poor

Description of categories above. (Click to expand)

Moral vision: Did the leader express attractive values, and did those values determine his or her motives? Did he or she have the emotional IQ to avoid contradicting those values because of personal needs?

Prudence: Did the leader have the contextual intelligence to wisely balance the values pursued and the risks imposed on others?

Use of force: Did the leader use it with attention to necessity, discrimination in treatment of civilians, and proportionality of benefits and damages?

Liberal concerns: Did the leaders try to respect and use institutions at home and abroad? To what extent were the rights of others considered?

Fiduciary: Was the leader a good trustee? Were the long-term interests of the country advanced?

Cosmopolitan: Did the leader also consider the interests of other peoples and minimize unnecessary damage to them?

Educational: Did the leader respect the truth and build credibility? Were facts respected? Did the leader try to create and broaden moral discourse at home and abroad?

Source: “Do Morals Matter? Presidents and Foreign Policy from FDR to Trump,” Joseph S. Nye Jr., Oxford University Press, 2020