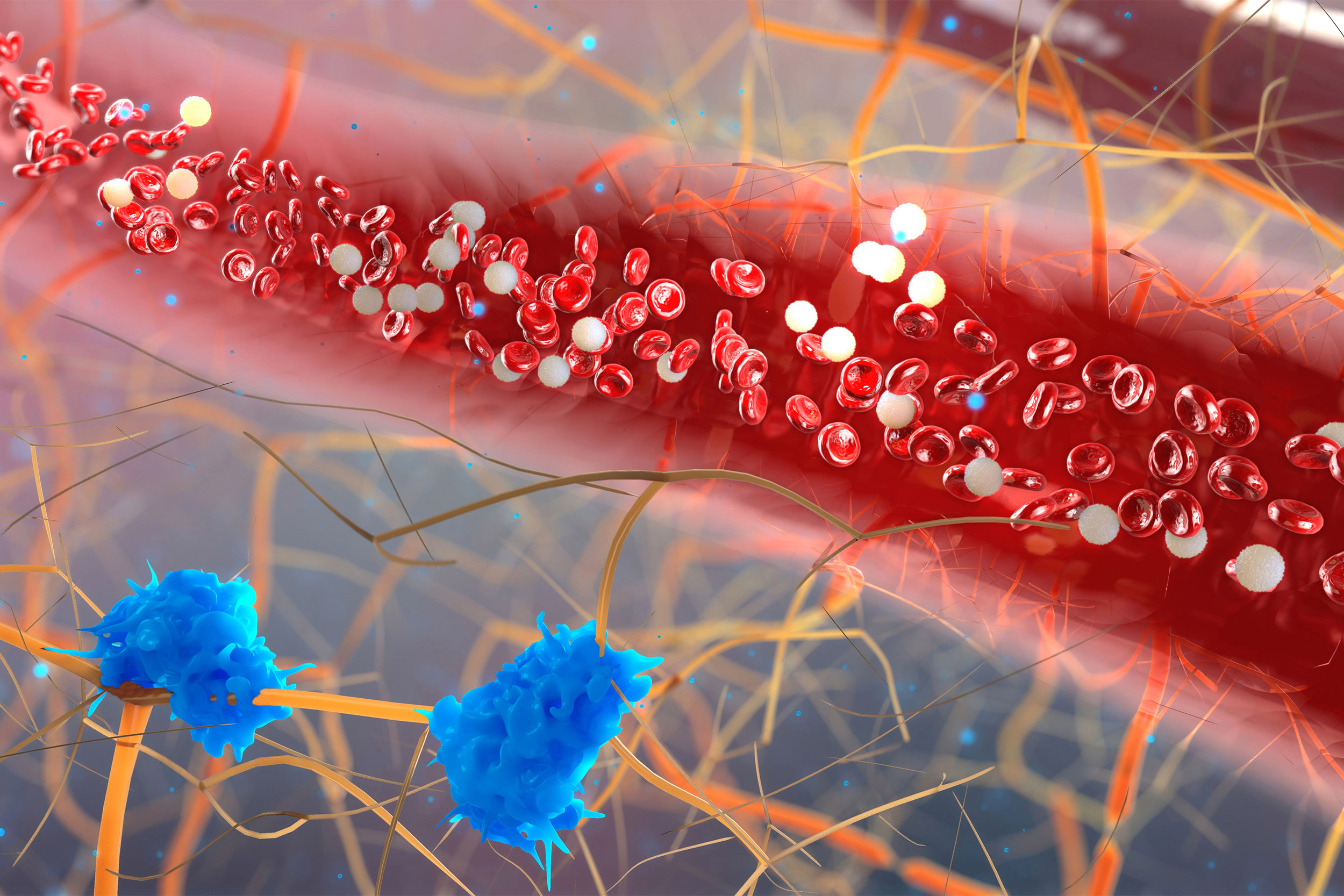

The body needs white blood cells — or leukocytes — to fight infection. However, a sedentary lifestyle can lead to inflammatory leukocytes, which can cause an increased risk for heart disease and strokes.

iStock

Exercise reduces chronic inflammation, protects heart, study says

After six weeks, mice had lower levels of inflammatory leukocytes

Scientists at Harvard-affiliated Massachusetts General Hospital (MGH) have identified a previously unknown biological pathway that promotes chronic inflammation and may help explain why sedentary people have an increased risk for heart disease and strokes.

In a study to be published in the November issue of Nature Medicine, MGH scientists and colleagues at several other institutions found that regular exercise blocks this pathway. This discovery could aid the development of new therapies to prevent cardiovascular disease.

Regular exercise protects the cardiovascular system by reducing risk factors such as cholesterol and blood pressure. “But we believe there are certain risk factors for cardiovascular disease that are not fully understood,” said Matthias Nahrendorf of the Center for Systems Biology at MGH. In particular, Nahrendorf and his team wanted to better understand the role of chronic inflammation, which contributes to the formation of artery-clogging blockages called plaques.

Nahrendorf and colleagues examined how physical activity affects the activity of bone marrow, specifically hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells (HSPCs). HSPCs can turn into any type of blood cell, including white blood cells called leukocytes, which promote inflammation. The body needs leukocytes to defend against infection and remove foreign bodies.

“When these [white blood] cells become overzealous, they start inflammation in places where they shouldn’t, including the walls of arteries.”

Matthias Nahrendorf

More like this

“But when these cells become overzealous, they start inflammation in places where they shouldn’t, including the walls of arteries,” said Nahrendorf.

Nahrendorf and his colleagues studied a group of laboratory mice that were housed in cages with treadmills. Some of the mice ran as much as six miles a night on the spinning wheels. Mice in a second group were housed in cages without treadmills. After six weeks, the running mice had significantly reduced HSPC activity and lower levels of inflammatory leukocytes than the mice that simply sat around their cages all day.

Nahrendorf explains that exercising caused the mice to produce less leptin, a hormone made by fat tissue that helps control appetite, but also signaled HSPCs to become more active and increase production of leukocytes. In two large studies, the team detected high levels of leptin and leukocytes in sedentary humans who have cardiovascular disease linked to chronic inflammation.

“This study identifies a new molecular connection between exercise and inflammation that takes place in the bone marrow and highlights a previously unappreciated role of leptin in exercise-mediated cardiovascular protection,” said Michelle Olive, program officer at the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Division of Cardiovascular Sciences. “This work adds a new piece to the puzzle of how sedentary lifestyles affect cardiovascular health and underscores the importance of following physical-activity guidelines.”

Reassuringly, the study found that lowering leukocyte levels by exercising didn’t make the running mice vulnerable to infection. This study underscores the importance of regular physical activity, but further focus on how exercise dampens inflammation could lead to novel strategies for preventing heart attacks and strokes. “We hope this research will give rise to new therapeutics that approach cardiovascular disease from a completely new angle,” said Nahrendorf.

The primary authors of the Nature Medicine paper are Nahrendorf, who is also a professor of radiology at Harvard Medical School; Vanessa Frodermann, a former postdoctoral fellow at MGH who is now a senior scientist at Novo Nordisk; David Rohde, a research fellow in the Department of Radiology at MGH; and Filip K. Swirski, an investigator in the Department of Radiology at MGH.

The work was funded by grants HL142494 and HL139598 from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI), part of the National Institutes of Health.