Among those at Radcliffe’s event, “Making the Cut: Promises and Challenges of Gene Editing,” were Charmaine Royal of Duke University (from left), Sylvain Moineau of the Université Laval, and Jonathan Kimmelman of McGill University.

Photos by Kris Snibbe/Harvard Staff Photographer

Power and pitfalls of gene editing

Radcliffe symposium examines the rapid advances brought by CRISPR

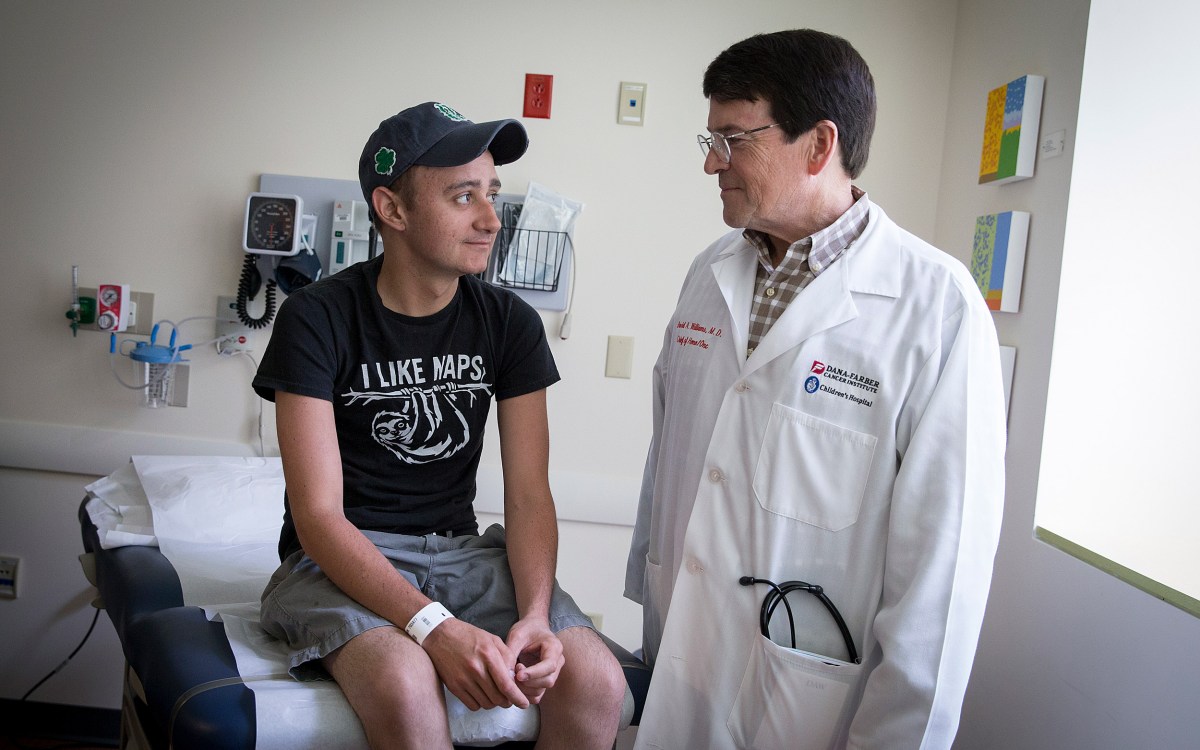

Can Anna Feurer’s genes be used to help 10-year-old Avery Watts?

Born with a genetic condition that results in life-threateningly high cholesterol, Watts travels twice a month to a Delaware hospital to have cholesterol filtered from her blood. Feurer, meanwhile, made headlines two years ago when scientists identified a mutation that protects her from heart disease by dramatically lowering levels of blood fats: triglycerides and LDL and HDL cholesterol.

Kiran Musunuru, a cardiologist and associate professor at the University of Pennsylvania’s Perelman School of Medicine, thinks gene therapy can help people like Watts. In recent experiments on rats bred to mimic Watts’ condition, Musunuru used CRISPR-Cas9 gene-editing technology to transfer into them an analog of Feurer’s cholesterol-lowering mutation. After the procedure, the rats’ blood cleared up within days.

“Can CRISPR fix the problem? The answer is yes. I think we can take the lessons learned from this person and use it to help this person,” Musunuru said.

Musunuru said that a similar one-time fix in humans is potentially helpful not just in extreme cases, but for anyone who suffers a heart attack. Though heart attack survivors typically leave the hospital with a prescription for cholesterol-lowering statins, Musunuru said, within a year less than half are still taking it. A one-time fix via gene therapy before leaving the hospital would likely be more effective.

“The drug doesn’t work if you don’t take it,” said Musunuru, who founded the Cambridge startup Verve Therapeutics to pursue the idea.

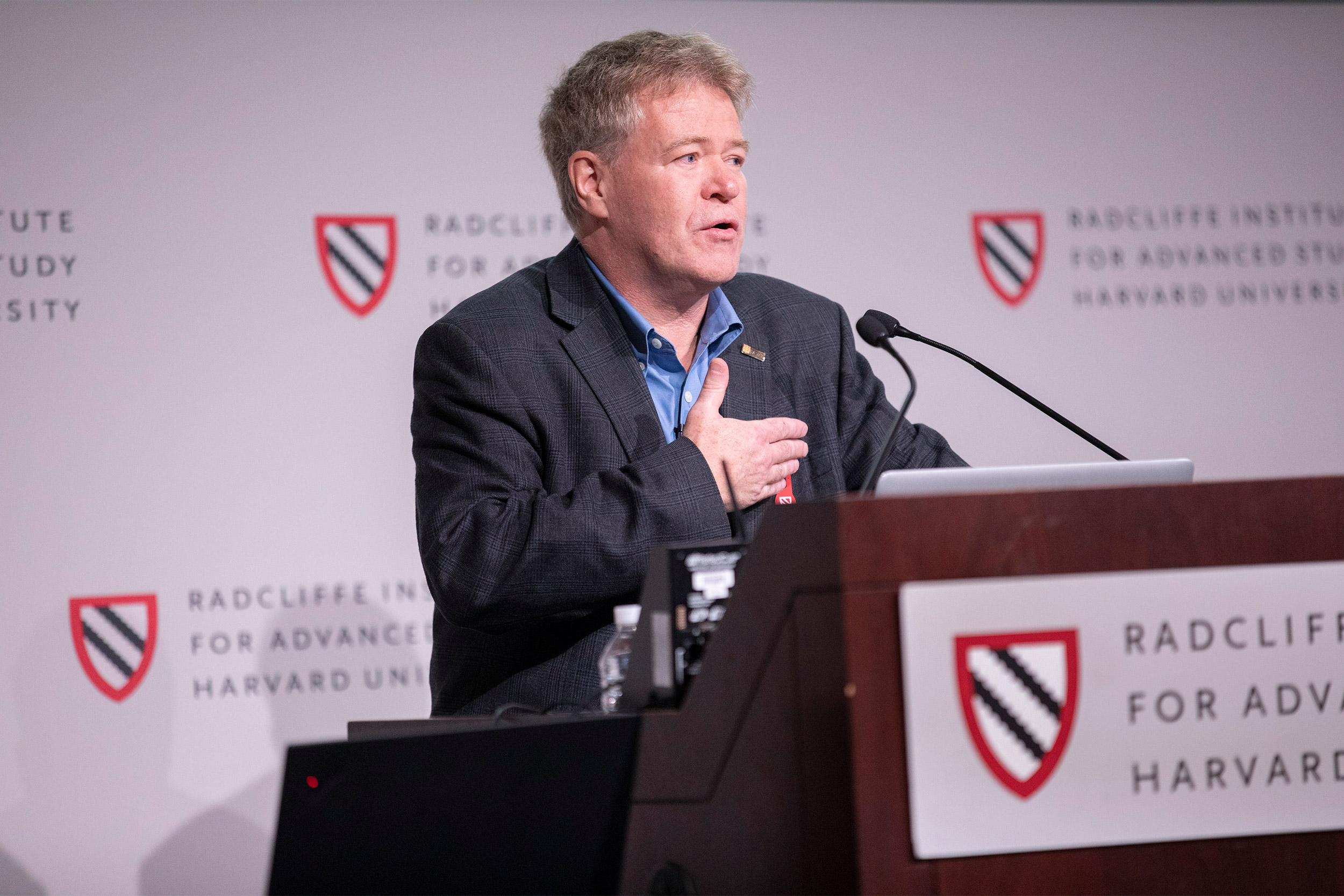

Musunuru was among group of experts gathered at the Radcliffe Institute for Advanced Study on Friday to discuss the promise and potential practical and ethical pitfalls posed by the rapid advance of gene therapy owing to CRISPR gene-editing technology.

The all-day event, “Making the Cut: Promises and Challenges of Gene Editing,” brought an audience of several hundred to Radcliffe’s Knafel Center for the institute’s annual science symposium.

Radcliffe’s Life Sciences Adviser, Immaculata De Vivo, highlighted the relatively short history of CRISPR technology, from its discovery as a naturally occurring bacterial immune system in 1987 to scientists’ use of it to precisely cut and edit DNA in 2011, to its application in human cells and, ultimately, its use in living humans, including the recent inauguration of a clinical trial for a treatment for sickle-cell anemia. Along the way, De Vivo said, it has been the enthusiasm and efforts of a global community of researchers that has pushed the technology forward.

“As a researcher, I can’t contain my own enthusiasm. It is quite remarkable,” said De Vivo, a professor at Harvard Medical School and the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health. “And it’s mostly because the entire world came together to work on this technology. … It is truly a multidisciplinary discovery and implementation in the clinical setting.”

Speakers discussed CRISPR science, which advances by some 6,000 new academic papers each year, a pace too fast for those interested in reading to keep up with, according to Sylvain Moineau, Canada Research Chair in Bacteriophages for the Université Laval in Quebec.

Though CRISPR’s potential to repair DNA-based conditions in human patients has grabbed headlines, Moineau said CRISPR has already had a major impact in the lab, one profound enough that he would judge the technology a success even if it is never used directly for human therapeutics.

“It’s a tremendous, tremendous research tool. To me, it’s already a success,” Moineau said.

While clinical applications are pending, the tool has the potential to impact agriculture even more rapidly, Sylvain said. He predicted a new generation of genetically modified plants, which may play important roles in feeding the globe’s rapidly rising human population at a time of increasing environmental stress.

The event also examined potential hurdles to the use of CRISPR-based therapies, such as the expense of bringing them to market, the temptation to take unethical shortcuts, and the difficulty of ensuring access to treatment to rich and poor alike.

Jonathan Kimmelman, James McGill Professor and director of the Biomedical Ethics Unit at McGill University, said despite CRISPR technology’s promise, its actual clinical impact when all is said and done may be low.

That’s because safety trials will inevitably slow progress and related science won’t stand still as trials drag on, Kimmelman said. The improved conventional treatments that result will erode the potential patient base for gene therapy. Safety trials will narrow the population further, ruling out use in children or other vulnerable groups, for example. Finally, practical concerns — cost and logistics — may rule out large populations in developing nations. In the end, he said, such “transformative” technology may indeed have an important impact, but it will likely be on a much narrower population than originally envisioned.

Panelists discussed the 2018 case of a Chinese scientist who used CRISPR to make heritable changes believed to protect against HIV to a set of twins. The controversial work highlights the importance of adopting ethical and regulatory guidelines around the world, panelists said.

As treatment options and ethical considerations are discussed, one critical population to involve is the disease community, according to Vence Bonham Jr., senior adviser to the director on genomics and health disparities at the National Human Genome Research Institute. Bonham ran focus groups of people with sickle cell disease in 2017, before the beginning of a gene therapy trial for that condition. Bonham found that the patient community was more willing than the general population to consider gene therapy, but nonetheless cautious about making changes that could be passed to future generations. Bonham quoted one participant: “Sometimes you are playing with things that should not be played with.”

[gz_banner_50states /]