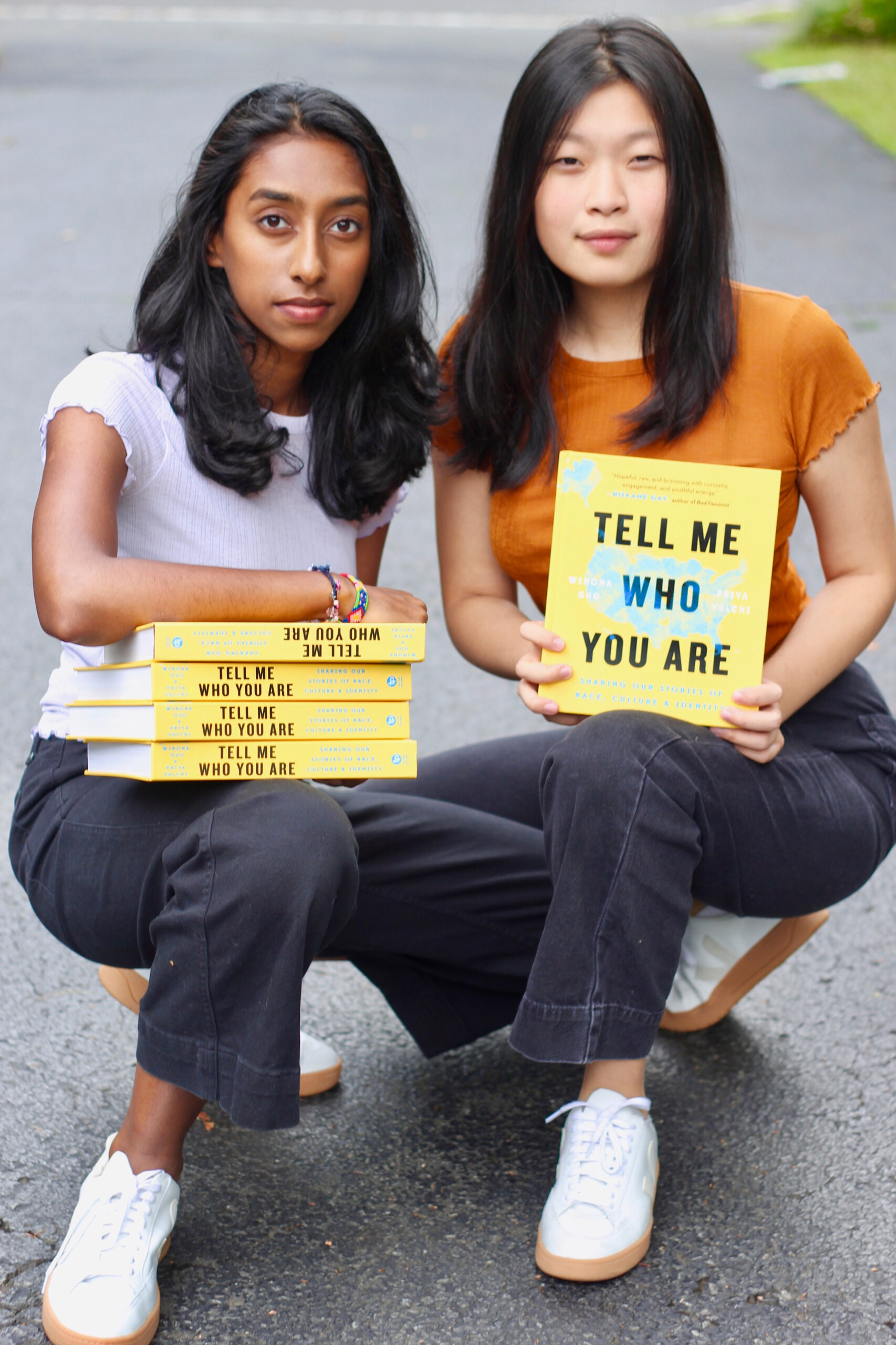

Winona Guo ’22 co-authored a book on race, culture, and identity as a resource for teachers.

Jon Chase/Harvard Staff Photographer

Choosing racial literacy

Sophomore Winona Guo co-wrote two textbooks, co-founded a nonprofit, and gave two TED Talks — most of it before she even graduated high school

Tell her the story of your life and she’ll listen, whether it takes five minutes or five hours.

It’s a simple thing, but it’s been at the heart of what Winona Guo ’22 has been doing for the past five years, documenting tales of race, culture, and identity in order to help change the ways racism is discussed — or not discussed — in the country’s K-12 classrooms.

“We are born into these racially divided worlds, so it’s never too early to learn, to think more about who we are and our world,” Guo said. “Maybe you grew up in an all-white town in Wyoming or maybe you grew up in a racially divided community in Chicago. No matter where you live in the United States, no matter who you are, race has been relevant to your life.”

Because of that, Guo believes that it’s important not only to be able to identify and talk about race and racism, but to acquire the tools to understand them in their historical, social, and cultural context, navigate pitfalls, and disrupt the corrosive effects of bigotry — especially for educators.

This is why Guo started her nonprofit, Choose, with a friend Priya Vulchi, now a sophomore at Princeton University, while the two were still high school students. Their aim is to promote racial literacy as advocates, authors, and speakers. To that end they have written two textbooks, given TED talks, developed resource materials for teachers, and collected hundreds of interviews on people’s experiences with race.

The idea for Choose sprang from a class conversation about race in the pair’s 10th-grade history course. It was the first time either remembered talking about it openly in school, and both thought it was the kind of exchange that should have been happening throughout their education. Now their goal is to have racial literary added to the national K-12 curriculum as a requirement.

“Both of us felt like we were being hit with water at the end of a hose,” Guo said about that class. “We felt like all of a sudden we’re hearing this language that articulated so much of our lived experience thus far.”

As a Chinese American, Guo recalls how in kindergarten a white girl didn’t want to play with her because she “didn’t want to hang out with girls like me” and “how there were these two white boys who would call me ‘China girl’ all the time and run away.” And, she said, those are just early examples.

Vulchi, who’s Indian American, had similar experiences. When she was young, other kids used to tell her that she really needed to bleach her dark skin to look better.

“Back then, I remember feeling so awful, because I truly believed that I was the problem,” Guo said. “I had learned, implicitly, to value my own worth as a human based on how close I could get to whiteness. I don’t think that would’ve changed without racial literacy.”

When they first started working on the project, the two read up on concepts like intersectionality, white privilege, and systemic racism. They spoke with peers and teachers. And they attended events in their hometown at Princeton University’s Department of African American Studies before venturing into downtown Princeton and later to Greater New York to interview people on the street about the effect race had on their lives.

Word spread about the project after the pair posted recordings of those stories along with pictures of interviewees on the Choose site and started talking with mentors and experts about what more could be done. That would eventually lead to Guo and Vulchi writing textbooks and giving TED talks about their experiences.

They self-published their first textbook, “The Classroom Index,” in 2017, their junior year of high school; it has been used by schools in more than 40 states. That text was largely funded by Princeton’s African American Studies Department after its chair, Eddie S. Glaude Jr., heard about the project from colleagues who’d met Guo and Vulchi at a university event.

“I thought it was just brilliant,” said Glaude. “I’ve always held the belief that the kinds of stories we tell shape who we take ourselves to be. Storytelling is important to character formation, so the way in which they wanted to ground [racial] experiences through stories seemed to be very, very important, particularly as a teaching tool in high schools and in elementary schools and middle schools.”

The second book, “Tell Me Who You Are,” was an expansion of the first, but in an effort to make it more representative of the country Guo and Vulchi took a gap year before college to travel to all 50 states and talk with more than 500 people about race — a journey they financed through personal fund-raising and corporate sponsorships.

That work was published in June by a division of Penguin Random House. It chronicles the cross-country trip while showing how racism plays out across the country every day through the more than 100 first-person accounts Guo and Vulchi selected for the book.

There is, for instance, the story of a Japanese American woman in Seattle who was sent to an internment camp during World War II. Then there is the one from the mother of Heather Heyer, who was killed by a car driven into a crowd of counterprotesters during the 2017 Unite the Right white-nationalist rally in Charlottesville, Va. Another comes from an Indian man in Kansas who was told by a white stranger to “get out of my country” before being shot. And there’s the saga of a transgender Latina in Philadelphia who explains why trans women of color have higher rates of participation in the sex trade.

“No matter where you live in the United States, no matter who you are, race has been relevant to your life.”

Winona Guo

Interviews ranged from five minutes to five hours, and the duo spoke with about 10 people a day. They started in Anchorage, Alaska, and traveled to a new state about every three days. At each location they stayed with a host, arranged before the trip began.

“It was a lot,” Guo said. “A lot of learning, a lot of growth, a lot of humility in realizing how much there was to learn, a lot of loving of each other and of beautiful souls we met across the country and a lot of strengthening each other to continue this work even when the emotional labor got really intense.”

For both books, Guo and Vulchi paired the stories with research, statistics, and history to give readers a social and cultural context. They want readers to empathize and connect with the person they are reading about while also gaining a larger understanding about how past and current events or key statistics have shaped and continue to shape contemporary race relations.

Today Guo and Vulchi continue their work on racial literacy, while maintaining full-time course loads. They have recently gone on a book tour, speaking at more than a dozen schools, conferences, and companies. They have also launched new projects. Over the summer, for instance, they established a fellowship for 41 educators to work on developing a racial literacy curriculum for all K-12 subject areas.

“A part of the reason we’ve focused our work on required curriculum is because we don’t think anyone should be able to opt out of conversations about something so fundamental to understanding who we are,” Guo said. In fact, she added, there is research that suggests that kids start developing signs of prejudice and stereotyping at 3 to 4 years old.

Vulchi agrees. The partners have discovered that their mission is “something that is beyond the two of us,” she said. “[This work] is a way for me to feel connected with this larger sense of purpose; it’s a way for me to feel like I’m not waiting for the real world or that I’m postponing action. I’m being a part of a solution towards racial justice and equity.”