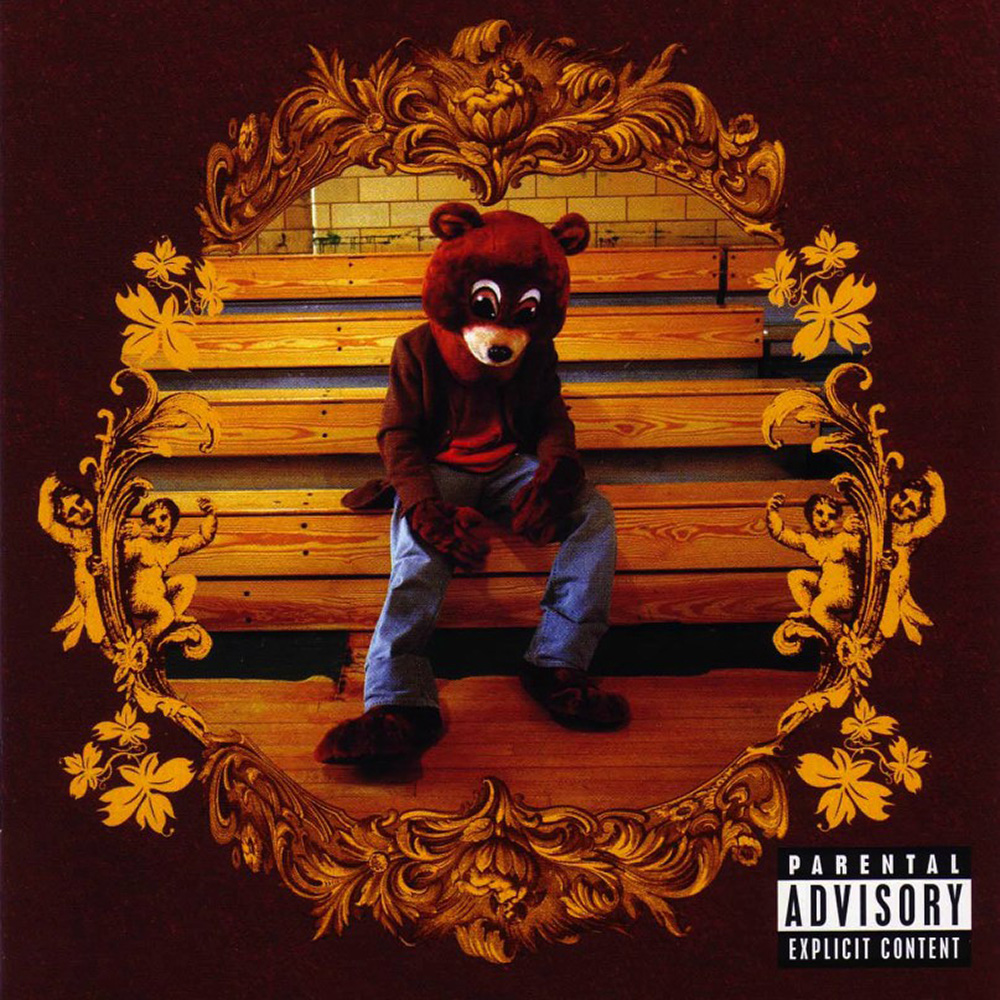

Inside the Hiphop Archive and Research Institute, Media and Publications Coordinator Makeda Daniel ’19 spins a Kanye West record on a turntable.

Kris Snibbe/Harvard Staff Photographer

Nas next to Mozart? Why not?

Harvard archive shines an academic light on the social, poetic, and musical complexities of hip-hop

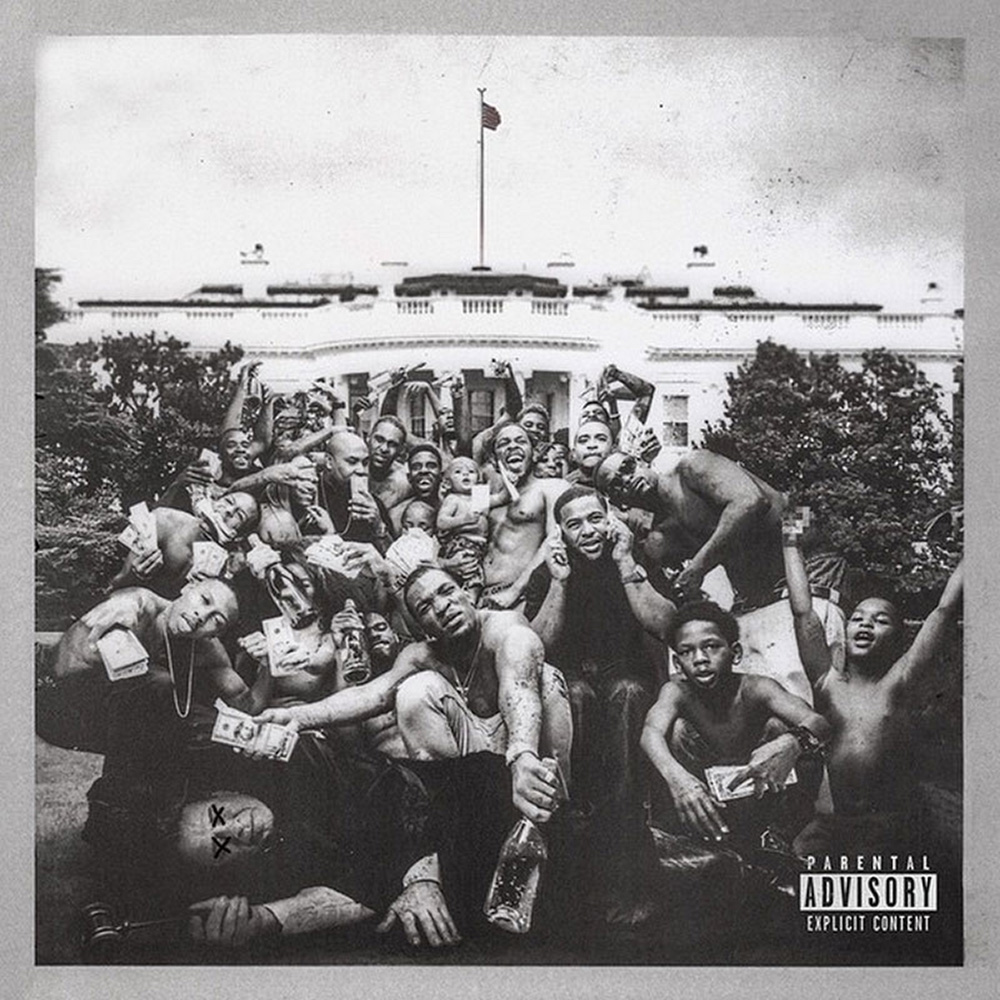

Like Shakespeare, Kendrick Lamar touches on the political and the personal, is a master of complex rhyme, and a pop-culture player in his time. Musically, his allusions, his samplings, are ironic, layer meaning, and recall jazz and modern poetry.

In the words of Biggie: “If you don’t know, now you know.”

Studying and preserving the work of Lamar and other hip-hop giants has been the focus of the Hiphop Archive and Research Institute, based at the Hutchins Center for African and African American Research, since its founding in 2002. The organization’s mission is to document the genre’s mushrooming influence on culture and society.

“What we try to do here is not run away from hard questions and hard ideas and things we disagree with about hip-hop, but to celebrate what it’s doing for us and what it’s doing for generations of Americans and also people throughout the world,” said Marcyliena Morgan, the archive’s founding executive director.

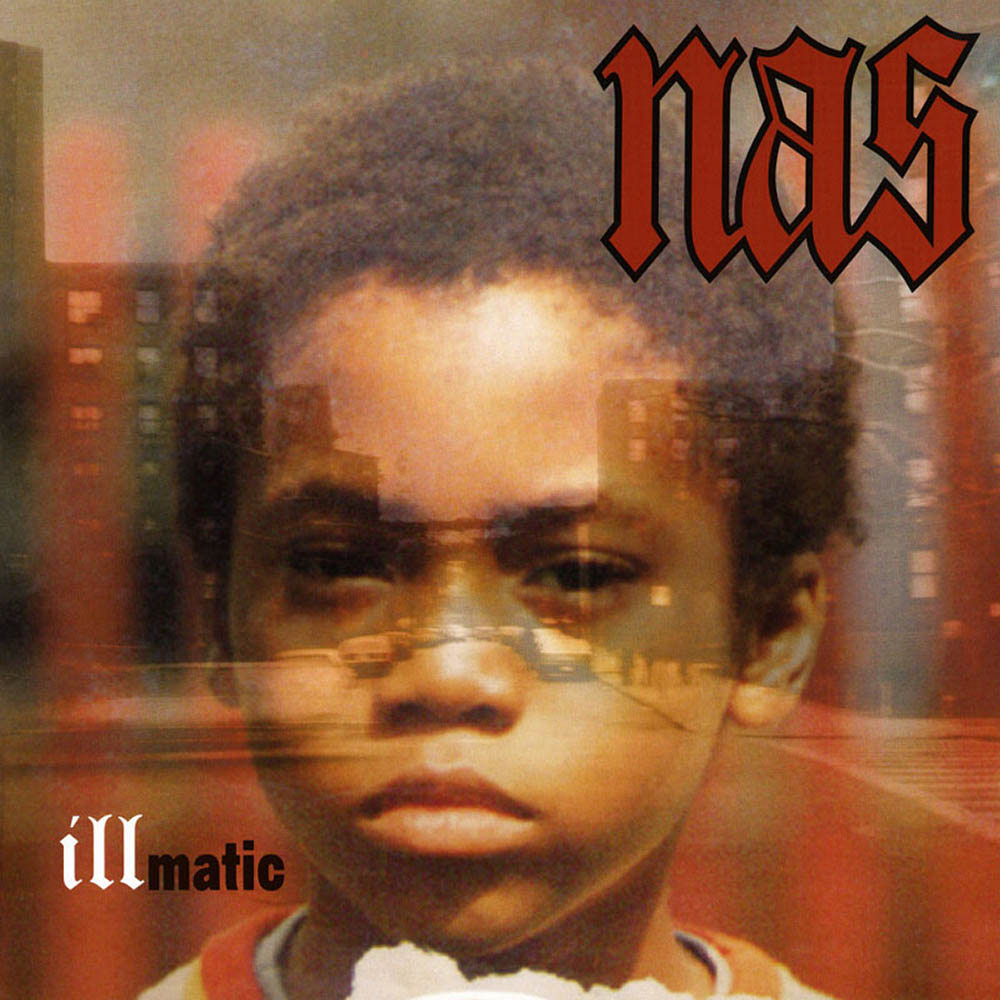

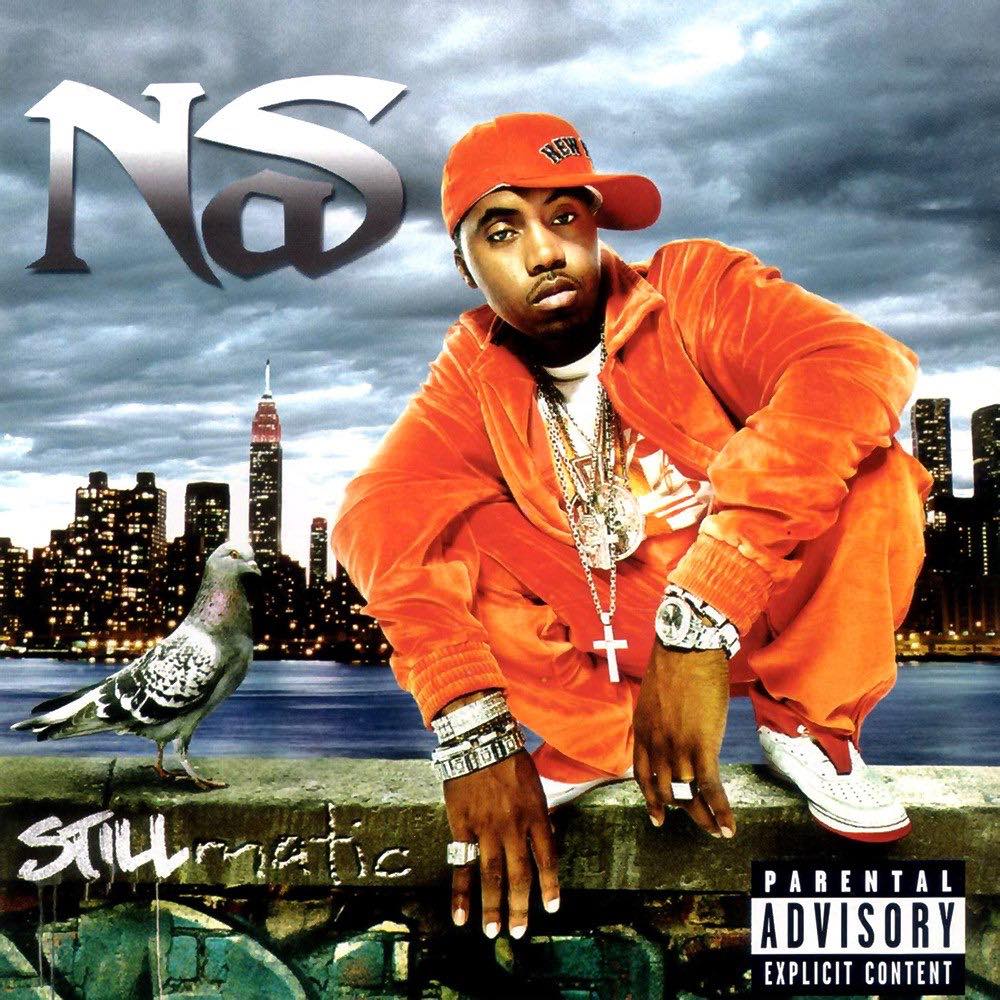

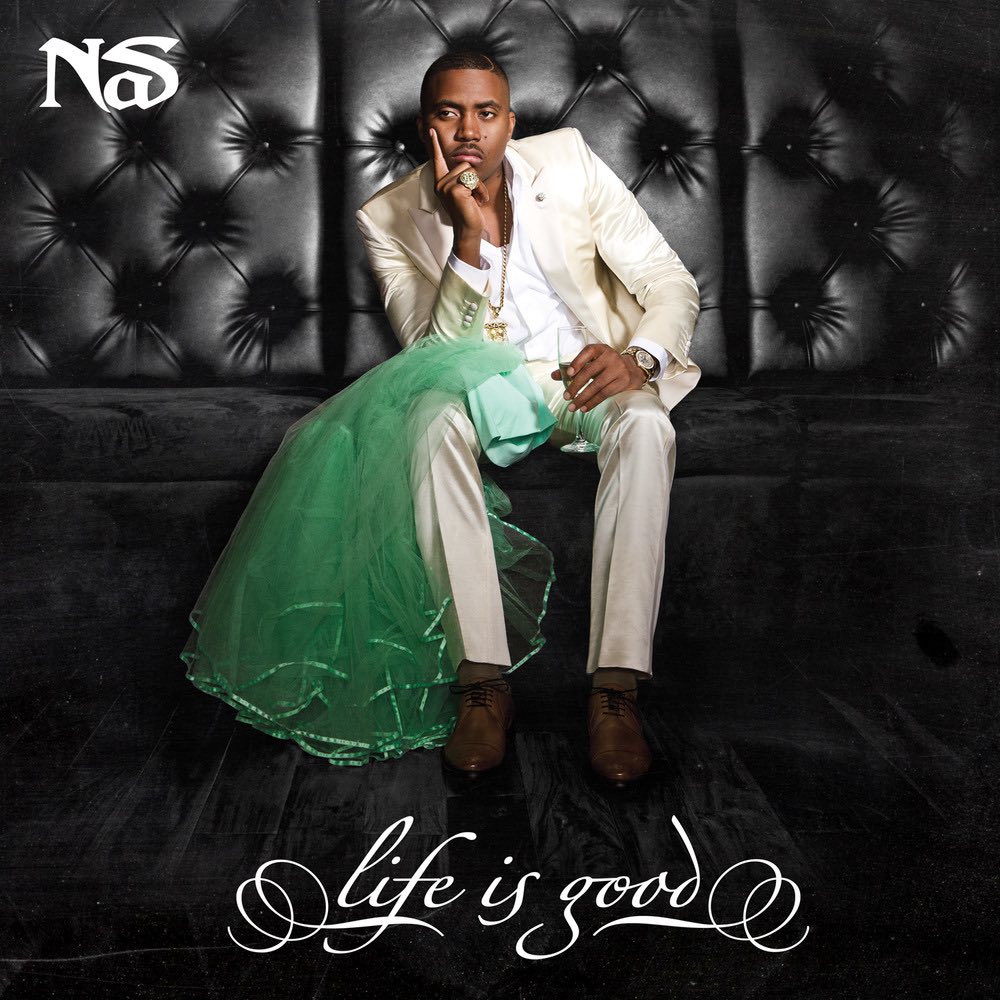

Through the years, the institute has established, along with the W.E.B. Du Bois Institute, the Nasir Jones Hiphop Fellowship for academic research in the field — named after rapper Nas whose poetic and prolific storytelling has immersed decades of fans in the reality and mentality of street life. It’s hosted artists, courses, programs, and events to explore hip-hop’s core elements — deejaying, rhyming, graffiti art, and b-boy and b-girl dance. And it’s collected stores of historic memorabilia and artifacts — classic vinyl records, vintage magazines, and scholarly articles and books on the subject.

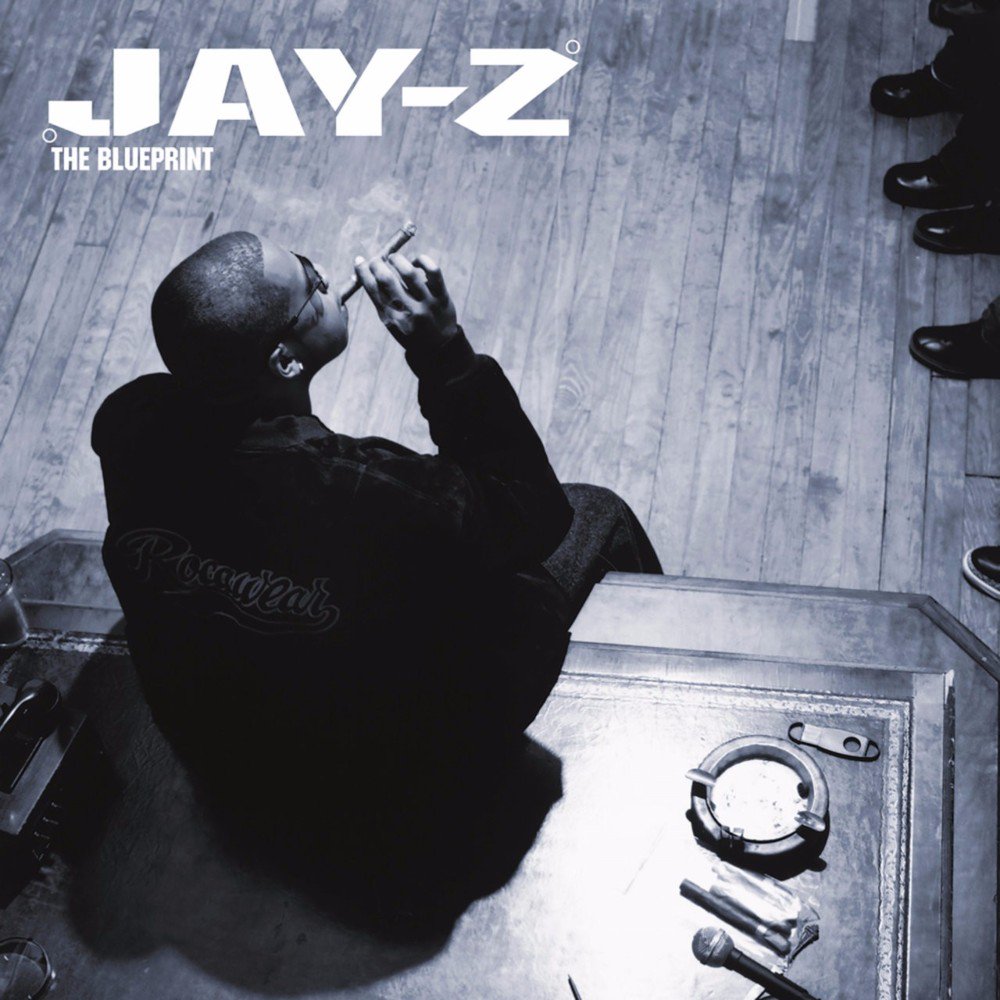

The archive occupies a sleek space decorated with graffiti-lettering, boom boxes, sneakers, a lit mini disco floor, and a turntable. Displays honor influential figures, like the late Tupac Shakur, Jay-Z, Queen Latifah, and Lauryn Hill — amid a constant soundtrack of background beats and raps.

Curator and producer Patrick Denard Douthit explains the criteria of what makes a hip-hop album a classic.

Since hip-hop emerged from Bronx house parties in the 1970s, the medium has become an undeniable fixture in the global music scene. Throughout its history hip-hop has chronicled a life experience that young, urban people of color have readily identified with — especially through artists and songs that embody the underdog mentality and rags-to-riches narrative.

In recent decades, the genre has achieved widespread acceptance in the U.S. For example, it’s not only the most popular genre of music among Americans, according to a multiple surveys and polls, but aspects of hip-hop culture has also infused television, film, fashion, and even politics.

And it has become an object of academic inquiry, said Morgan, who’s also the Ernest E. Monrad Professor of the Social Sciences and a professor of African and African American studies. Besides Harvard, universities such as Penn State, USC, UCLA, Stanford, Duke, Princeton, and NYU have offered courses in it. And in 2010 the Yale University Press published a 928-page “Anthology of Rap,” the first major print collection of lyrics, edited by Adam Bradley and Andrew DuBois, both of whom earned PhDs in English from Harvard. (And included a preface by Henry Louis “Skip” Gates Jr., Alphonse Fletcher Jr. University Professor and director of the Hutchins Center for African and African American Research, which notes that “[r]ap’s tradition is as broad and as deep as any other form of poetry.”)

Image gallery

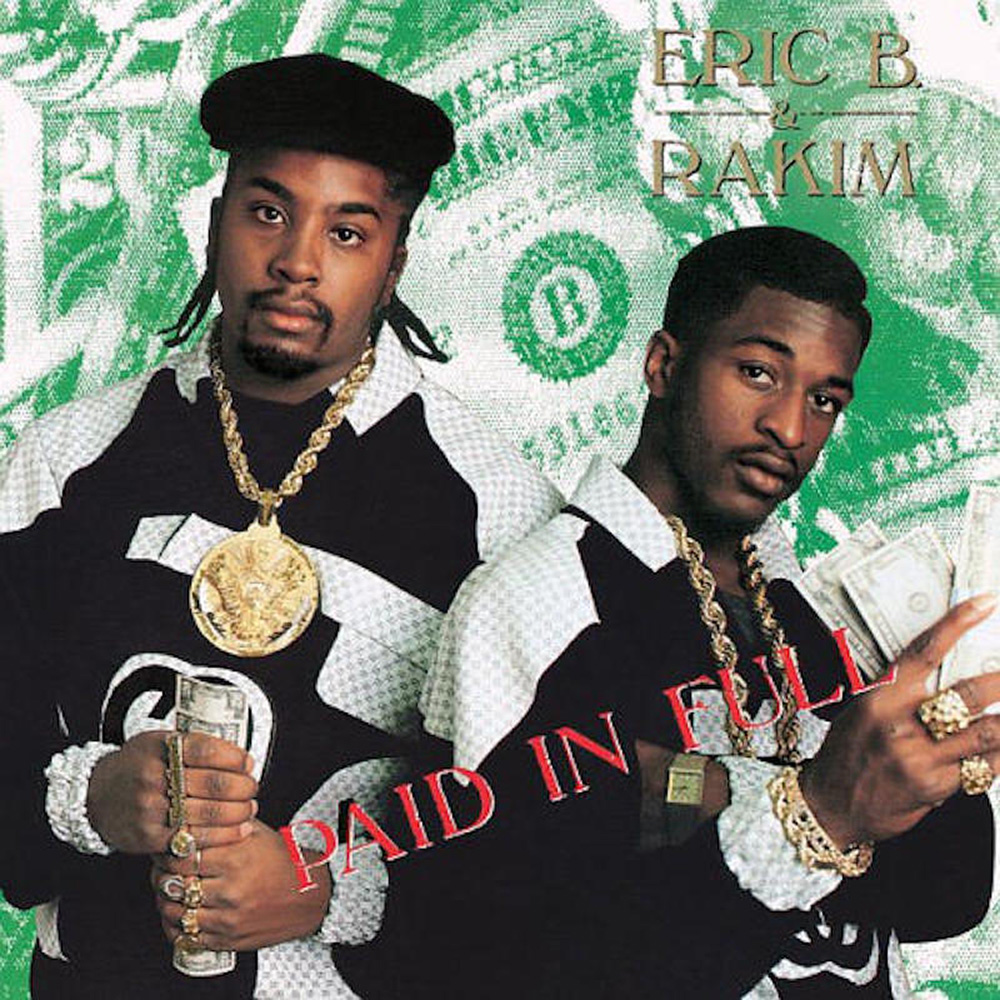

Eric B. and Rakim, Paid in Full (1987)

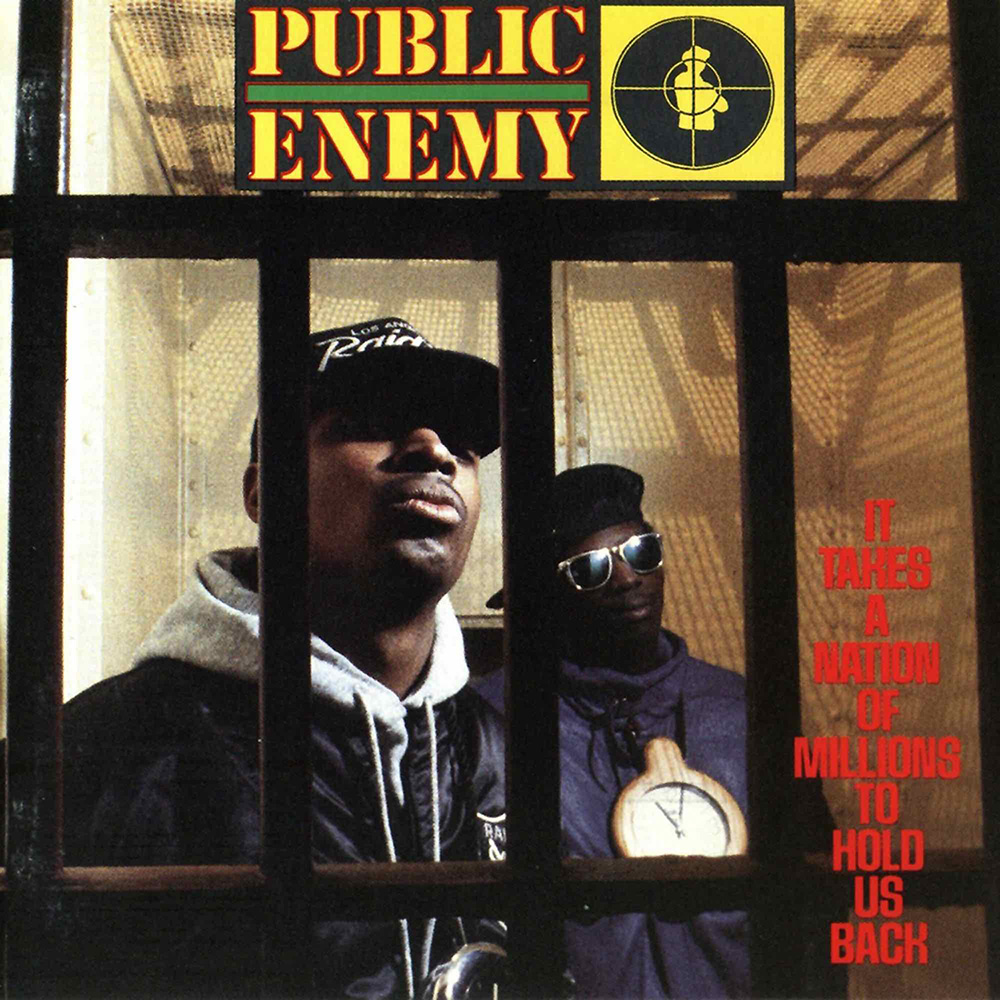

Public Enemy, It Takes a Nation of Millions to Hold Us Back (1988)

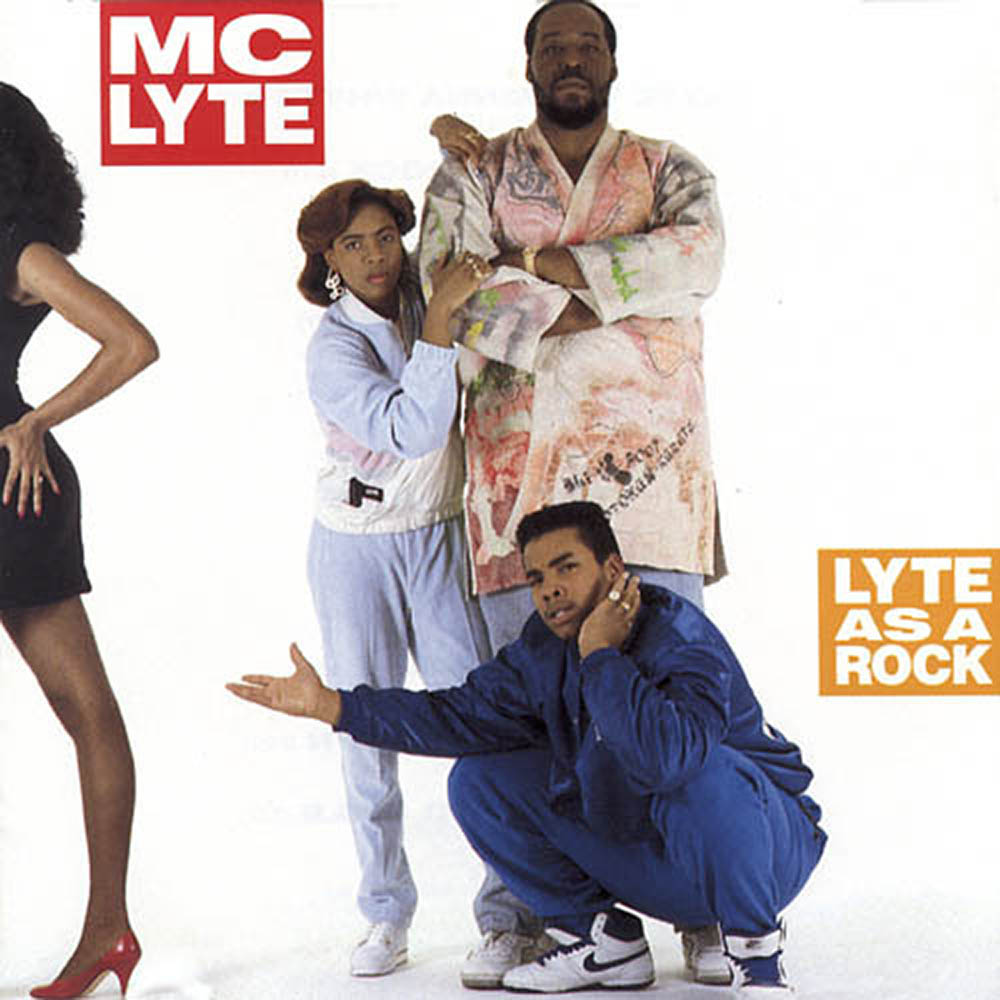

MC Lyte, Lyte as a Rock (1988)

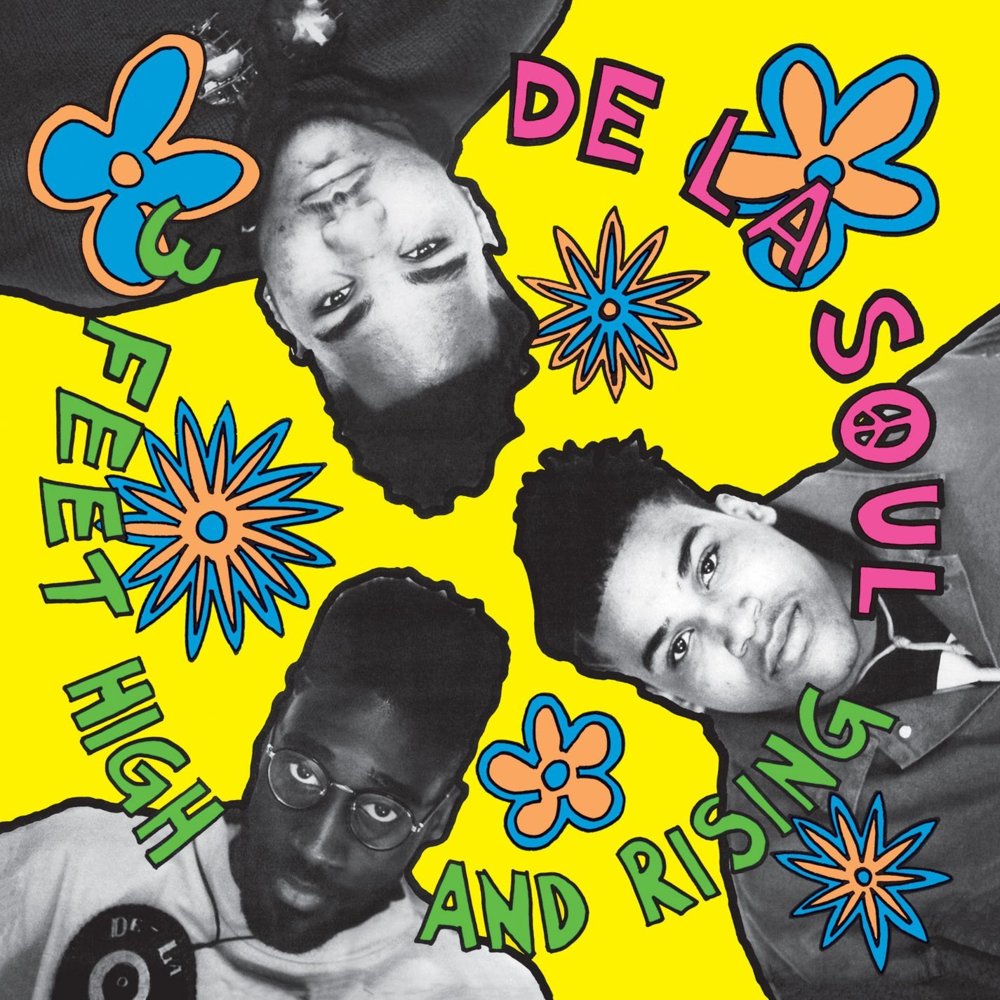

De La Soul , 3 Feet High and Rising (1989)

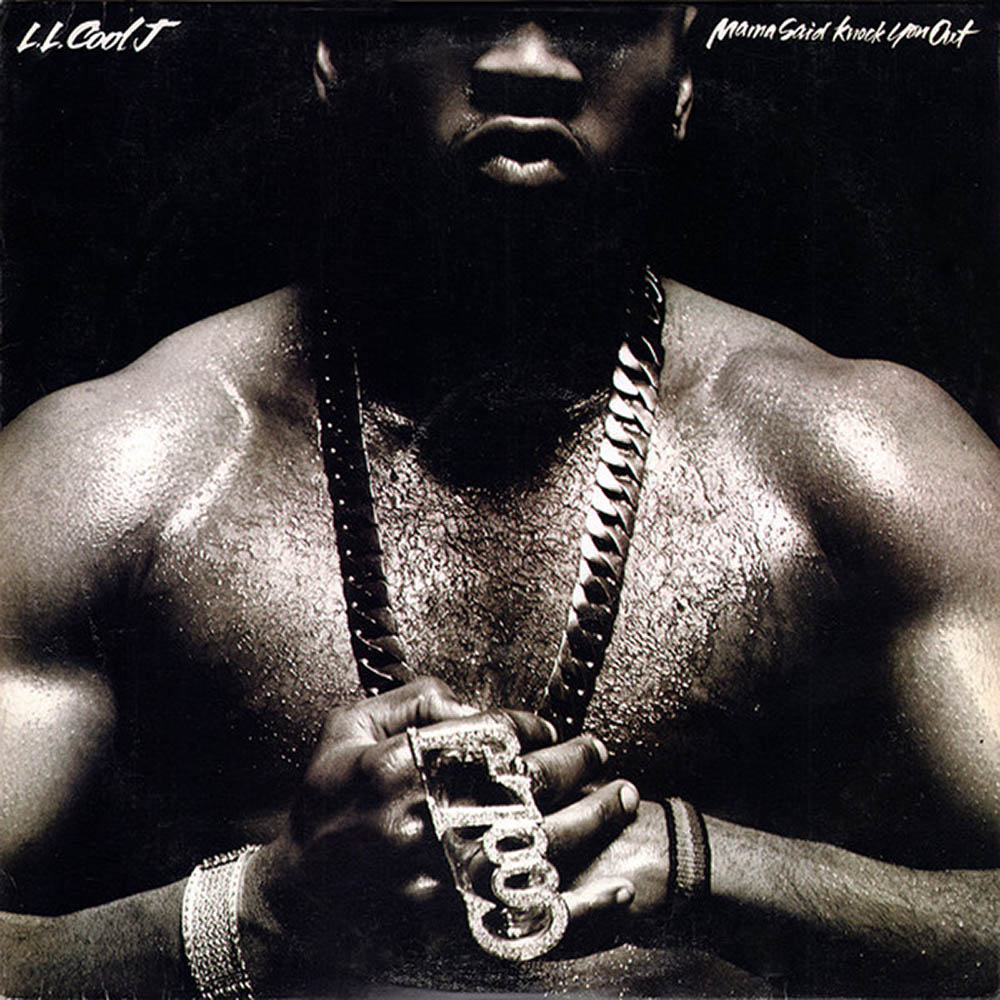

LL Cool J, Mama Said Knock You Out (1990)

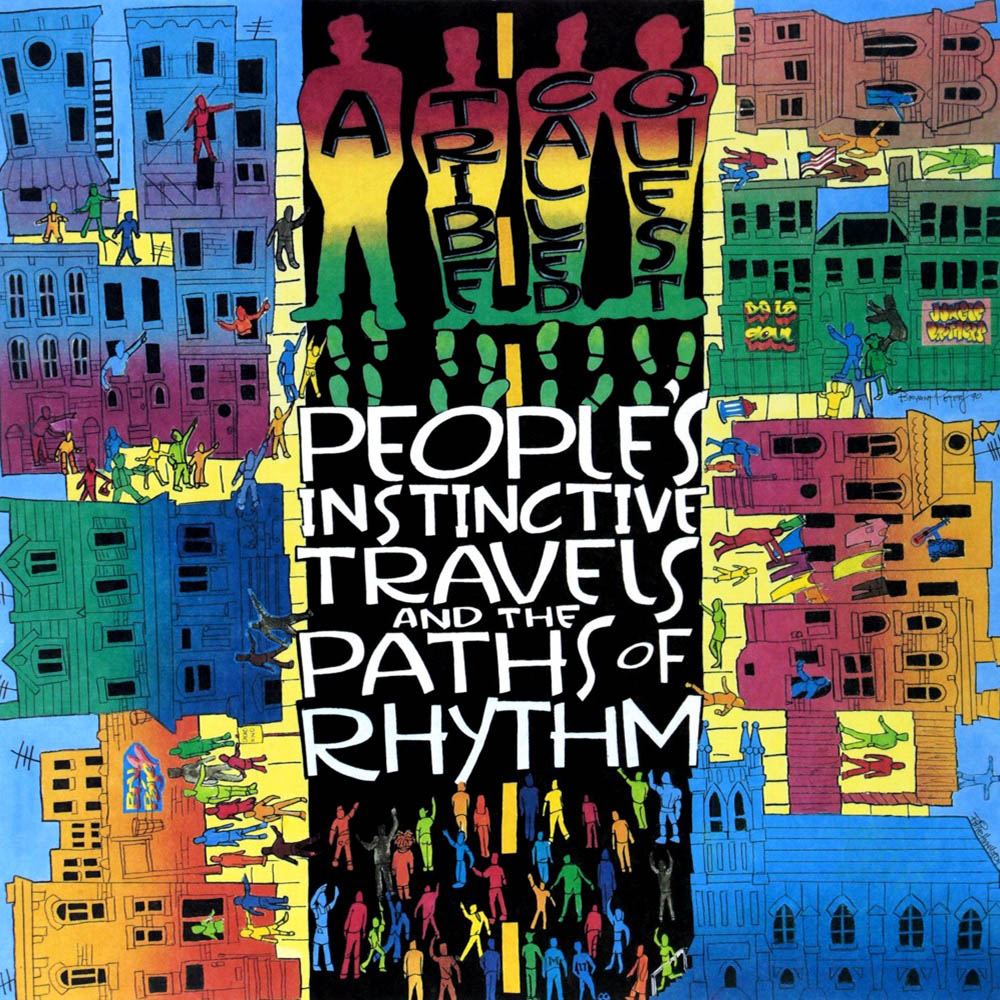

A Tribe Called Quest, People’s Instinctive Travels and the Paths of Rhythm (1990)

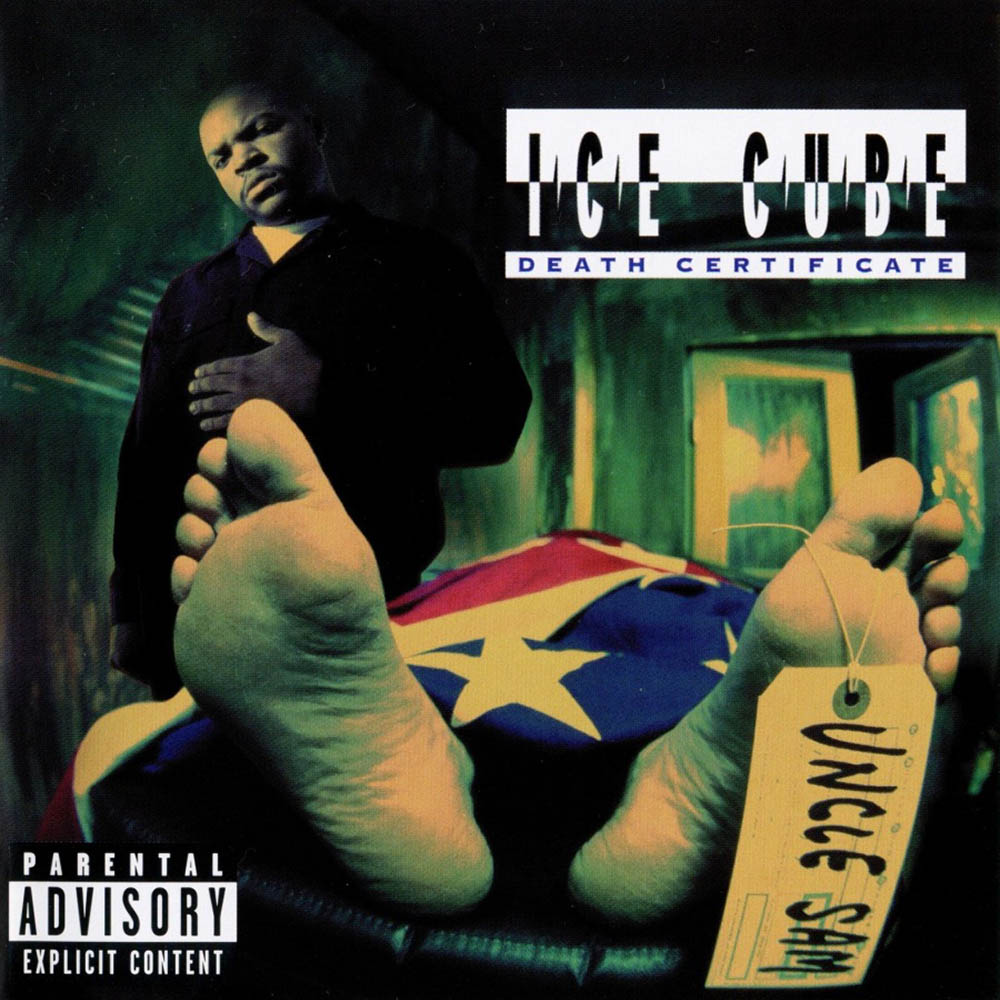

Ice Cube , Death Certificate (1991)

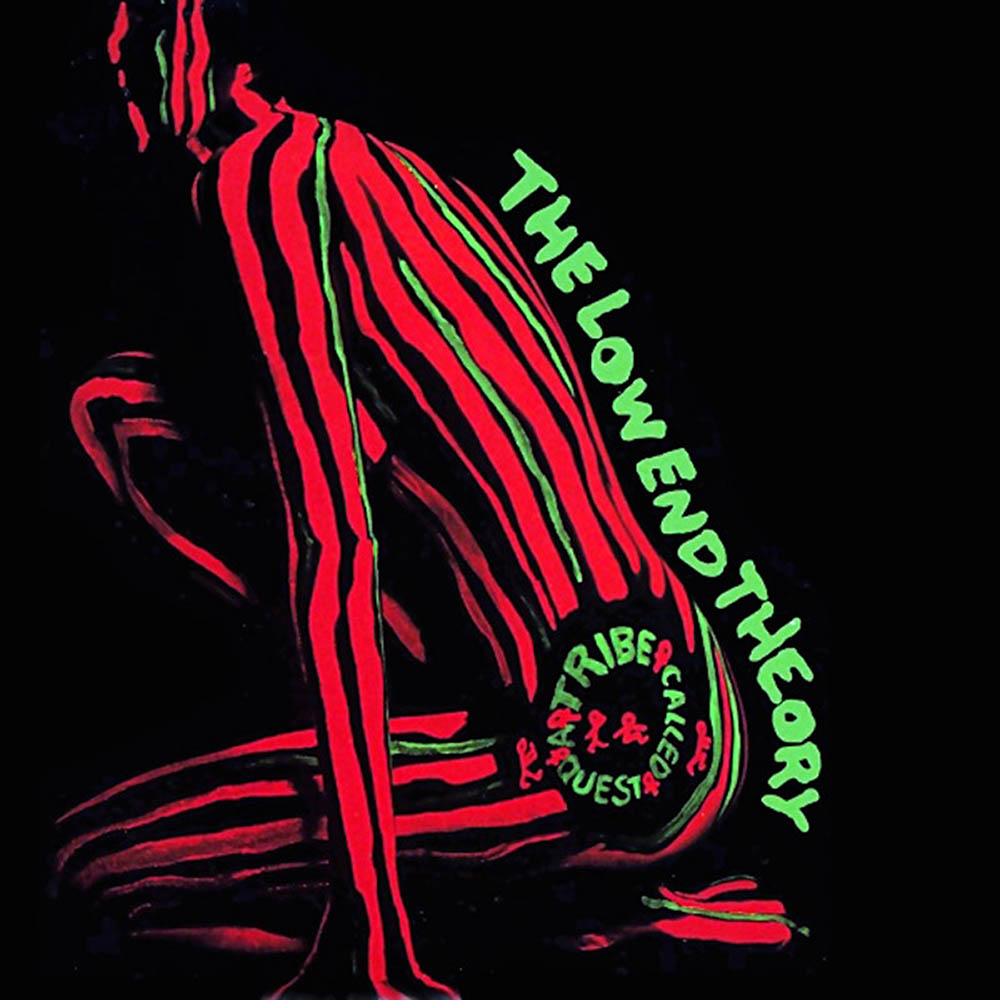

A Tribe Called Quest, The Low End Theory (1991)

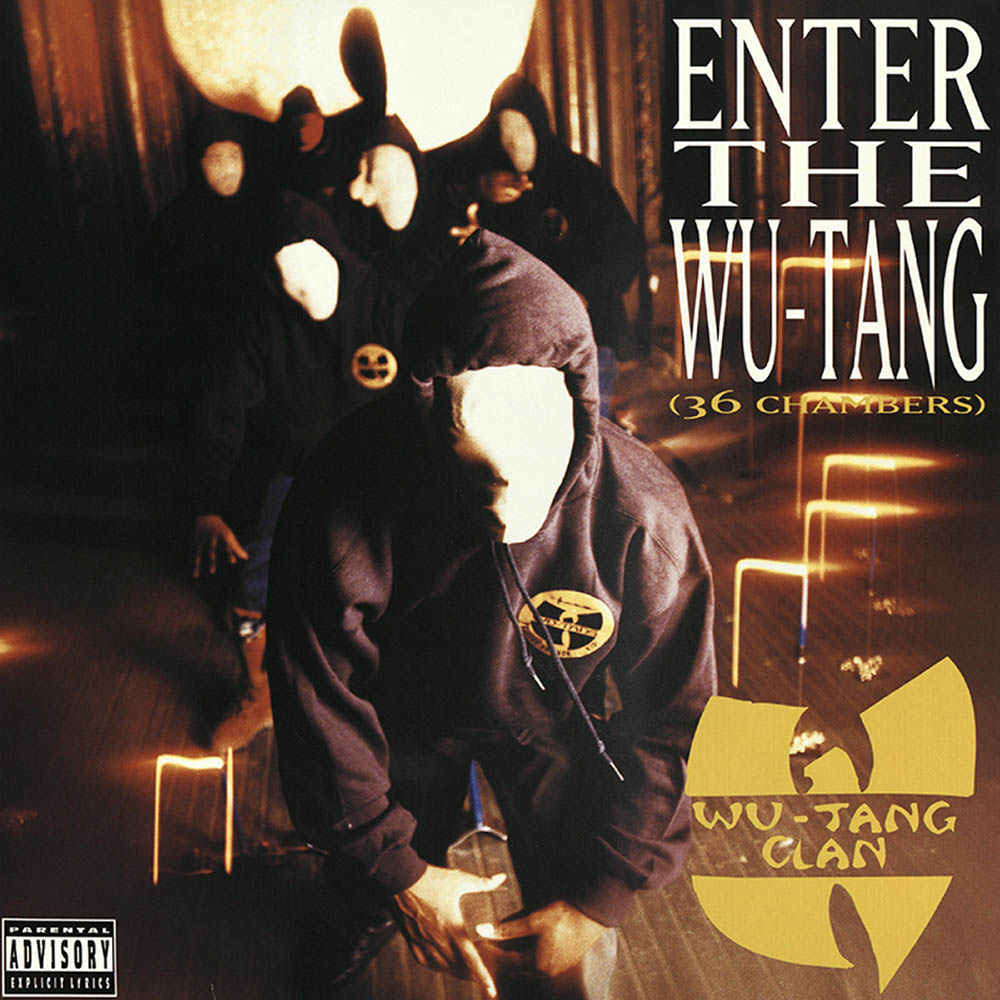

Wu-Tang Clan, Enter the Wu-Tang: 36 Chambers (1993)

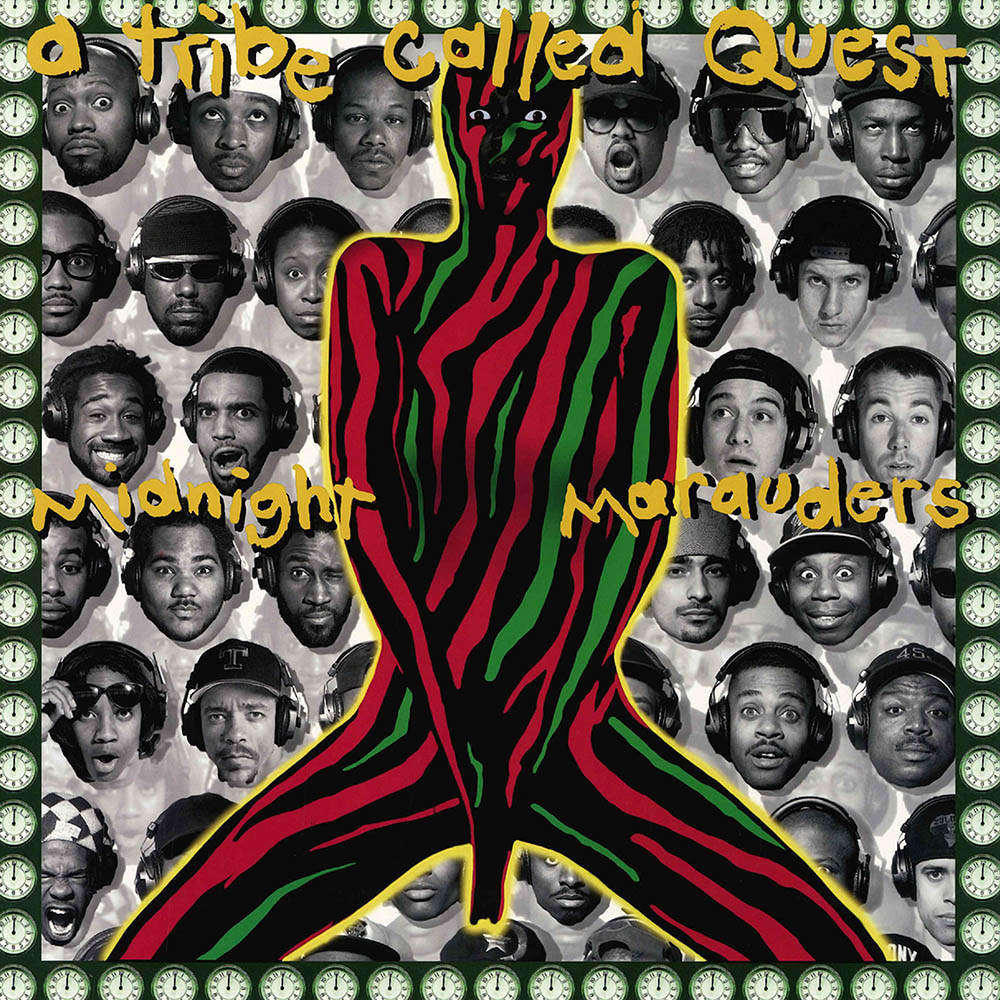

A Tribe Called Quest, Midnight Marauders (1993)

Nas, Illmatic (1994)

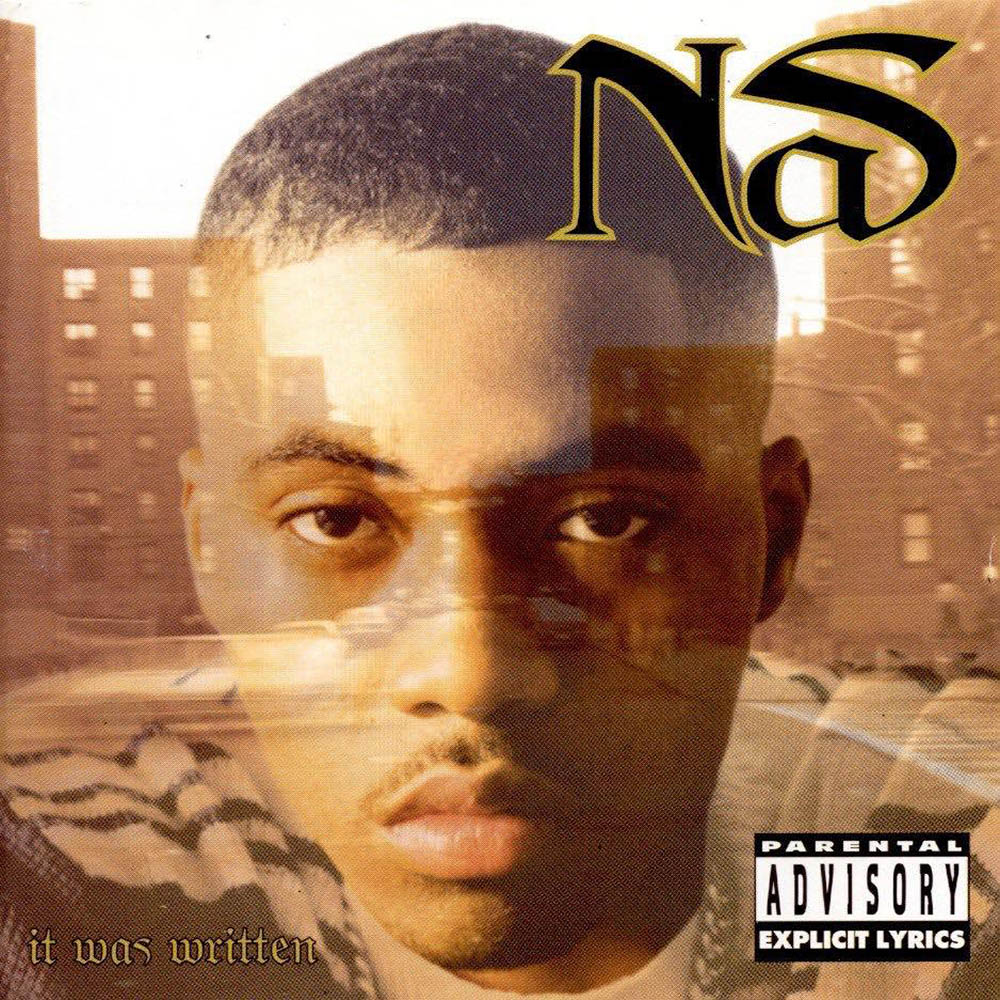

Nas, It Was Written (1996)

The Fugees, The Score (1996)

Missy Elliott, Supa Dupa Fly (1997)

OutKast, Aquemini (1998)

Lauryn Hill, The Miseducation of Lauryn Hill (1998)

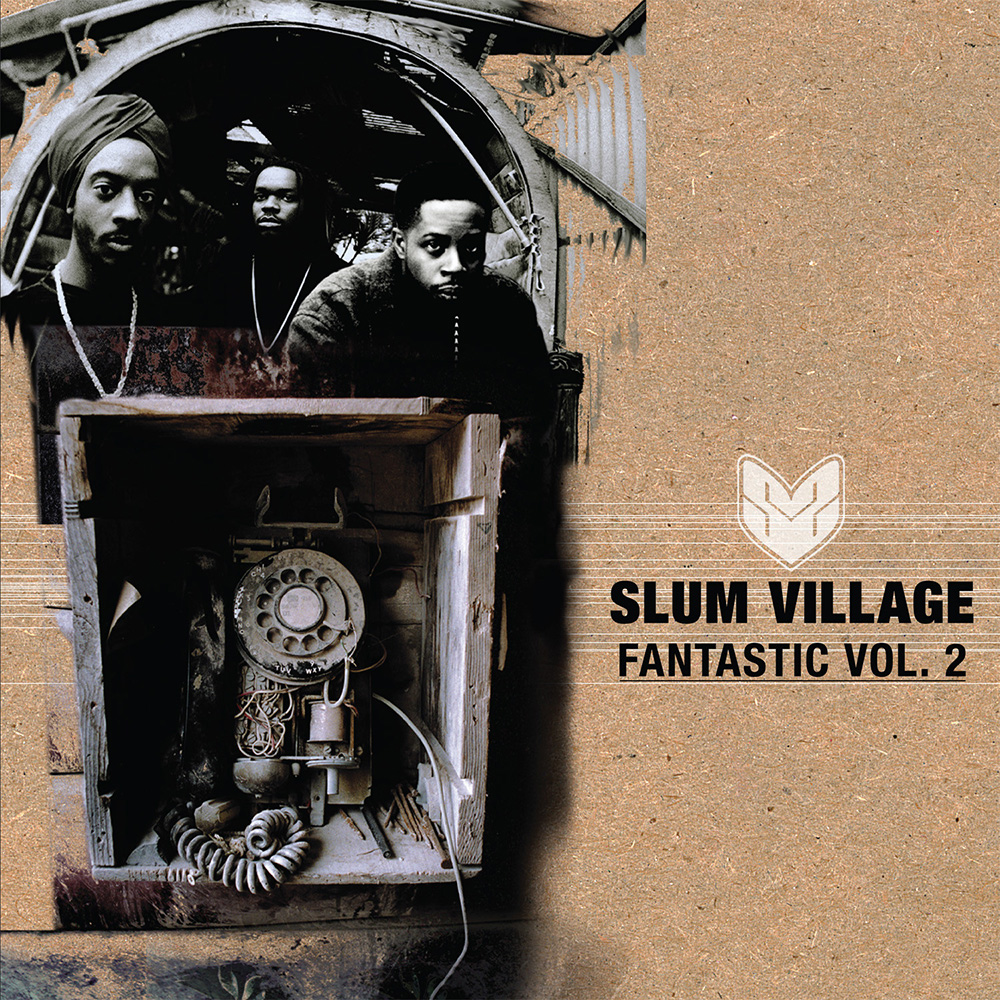

Slum Village, Fantastic, Vol. 2 (2000)

Nas, Stillmatic (2001)

Jay Z, The Blueprint (2001)

Kanye West, The College Dropout (2004)

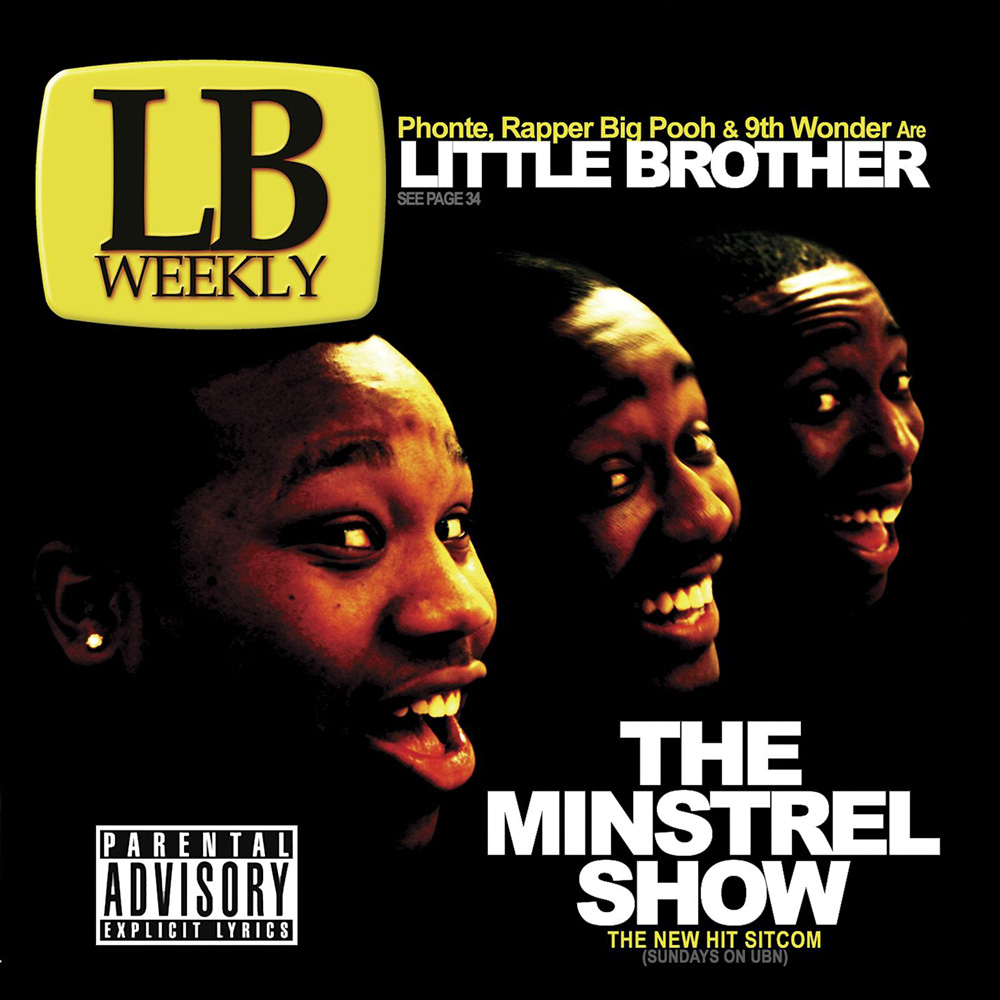

Little Brother, The Minstrel Show (2005)

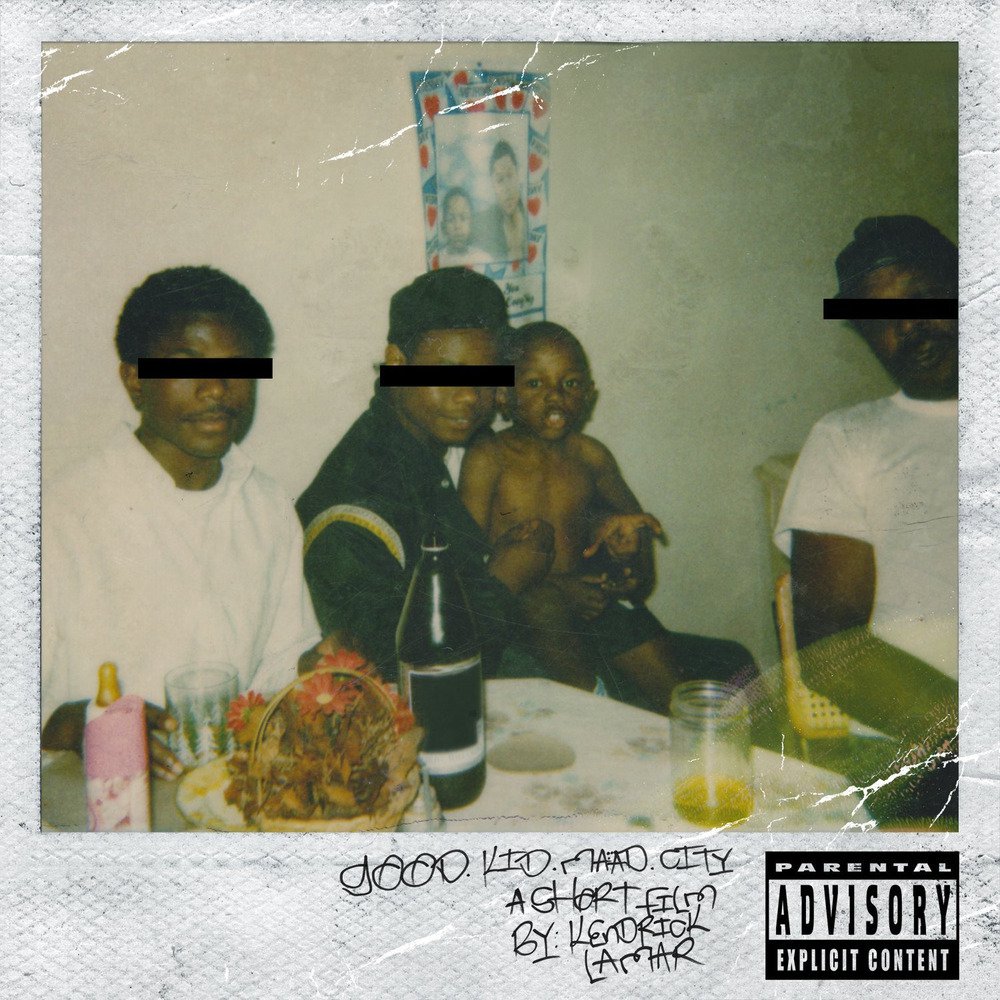

Kendrick Lamar, good kid, m.A.A.d city (2012)

Nas, Life Is Good (2012)

Kendrick Lamar, To Pimp A Butterfly (2015)

The Hiphop Archive’s 24 albums.

“If hip-hop has this notion that you’re supposed to ‘keep it real’ and you have to have an analysis and critique in order to keep it real, and you’re supposed to work at the highest possible level, and you’re supposed to ‘know it’ and ‘know who you are’ — it fits Harvard in many ways,” Morgan said.

The institute also maintains Classic Crates, an archiving collection where 200 of hip-hop’s most seminal albums will be stored in the Eda Kuhn Loeb Music Library, the University’s primary archive of music and music materials from around the world.

Working closely with curator Patrick Denard Douthit, better known as super producer 9th Wonder, the archive so far includes 24 albums, ranging from late ’80s producer and emcee duo Eric B. and Rakim to contemporary superstars like Kanye West. 9th Wonder spent the 2012-2013 year as a fellow and lecturer at the archive and has worked with some of the industry’s biggest stars.

Inside the Hiphop Archive and Research Institute, founding executive director Marcyliena Morgan shows off the collection.

Kris Snibbe/Harvard Staff Photographer

The archive offers annotated lyrics to specific songs that track musical and poetic allusions and analysis of technique and provides historical and contextual footnotes, along with liner notes.

“You’re really breaking it down into a hundred different layers, and you’re trying to go through each layer and see why it was so intentional,” said Makeda Daniel ’19, a publications and media coordinator at the archive.

The institute has attracted notable visitors like artists Chance the Rapper, J. Cole, Jill Scott, Lupe Fiasco, and Nas. Morgan brought the idea for a hip-hop archive to Harvard from UCLA, where she was a professor of linguistics in the 1990s, after students there convinced her about the underground culture being formed through the elements of hip-hop and how it had influenced their lives.

More than 20 years later, that influence is stronger than ever among the next generation. Daniel, who started at the archive in 2016 as a student research assistant, believes it’s because ultimately hip-hop is a story that is easy to relate to.

“You have success. You have pain. You have trauma,” Daniel said. “It intersects and it’s representative of a narrative that always comes back to being a rebel.”