Photos courtesy of Countway Library

Bringing the Bone Box back to life

3D printing enables Countway Library to revive 1800s human skeletal study program

Harvard Medical School (HMS) students used to be able to check out a set of human bones the way library users today would borrow a book. The so-called Bone Box program ran from the late 19th through the mid-20th century, and was intended to help students study anatomy at home.

Now, staff members at the Medical School’s Countway Library are reviving the initiative with a 21st-century twist. They’re planning to assemble new boxes of replica human bones and skulls rendered through 3D printing in a program they’re calling Beyond the Bone Box.

Dominic Hall, a curator for the Warren Anatomical Museum at Countway Library, and Anne Harrington, the Franklin L. Ford Professor of the History of Science at HMS, are spearheading the project. The pair have developed a plan that they believe resolves the concerns that scuttled the original.

“This is a program that was extremely valuable in its first iteration, and now could be made even more useful,” said Harvard Library Associate Director Claire Demarco, whose Office of Digital Strategies and Innovation awarded the project an S.T. Lee Innovation Grant in 2018. The Lee initiative is intended to spur creative endeavors that promote library holdings.

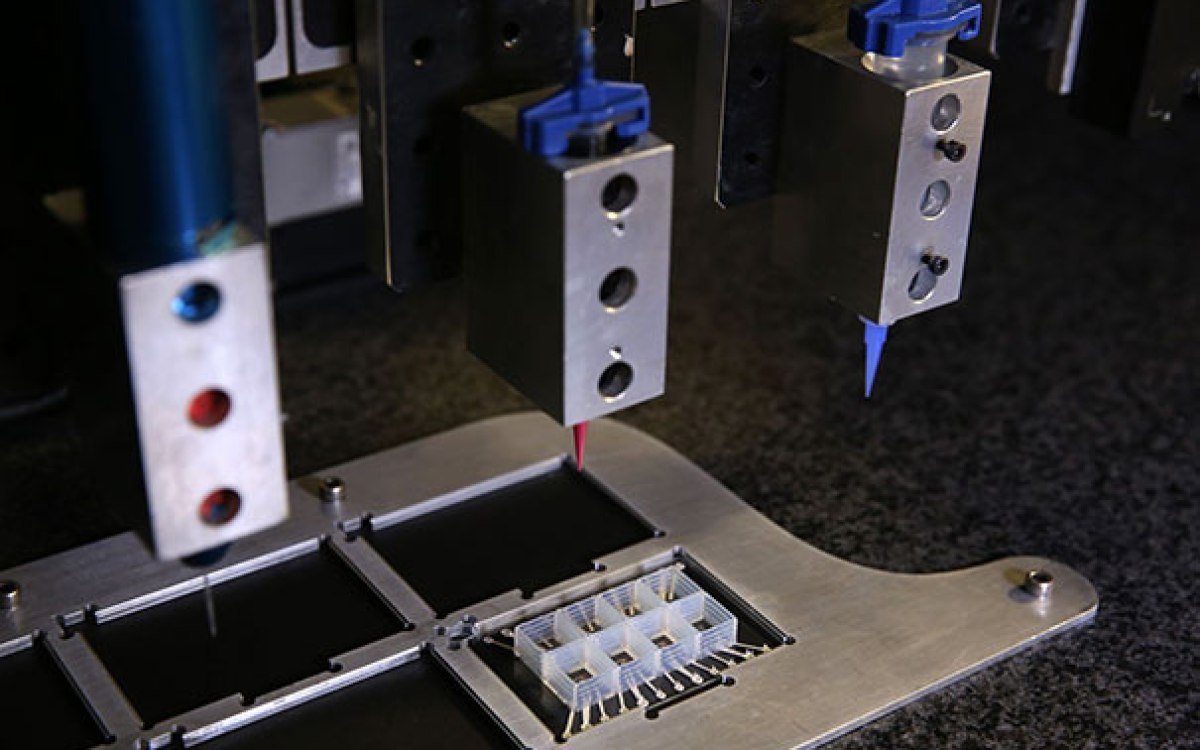

Hall and Harrington used the grant funds to buy a 3D printer, which has enabled much broader use of the collections at Countway Library. The library houses an anatomical museum, which is expected to preserve rare anatomical specimens in perpetuity, but as part of the library system, it also has an educational mission. Creating 3D models of rare specimens allows the museum to safeguard the originals while still allowing Countway’s special collections to be used as teaching tools.

The Bone Box program’s history is storied. Begun in 1881 by Medical School Professor Oliver Wendell Holmes Sr., father of the namesake Supreme Court justice, the initiative gave decades of doctors in training the valuable opportunity to study human skeletons outside the classroom. The program was eventually shuttered owing in large part to ethical issues around circulating real human remains.

3D printing a skull in action.

Video: Alyssa Brophy/Warren Museum

For starters, many collectors in the 1800s did not seek consent from people before collecting their remains. Sometimes they were purchased from individuals or companies; in some cases they were stolen from graveyards. Even though Countway Library now owns these collections, Hall said, that doesn’t necessarily mean that it’s ethical to use them without giving proper context alongside the reproductions.

Demarco added that even if an individual donated their body to science, it doesn’t necessarily mean they would want it reproduced.

Hall and Harrington think they have found ways to minimize those concerns by focusing on already well-known examples from Countway’s anatomical collections. The new boxes will also include reproductions of primary sources, such as manuscripts that explain how the bones were used in the study of medicine in the period.

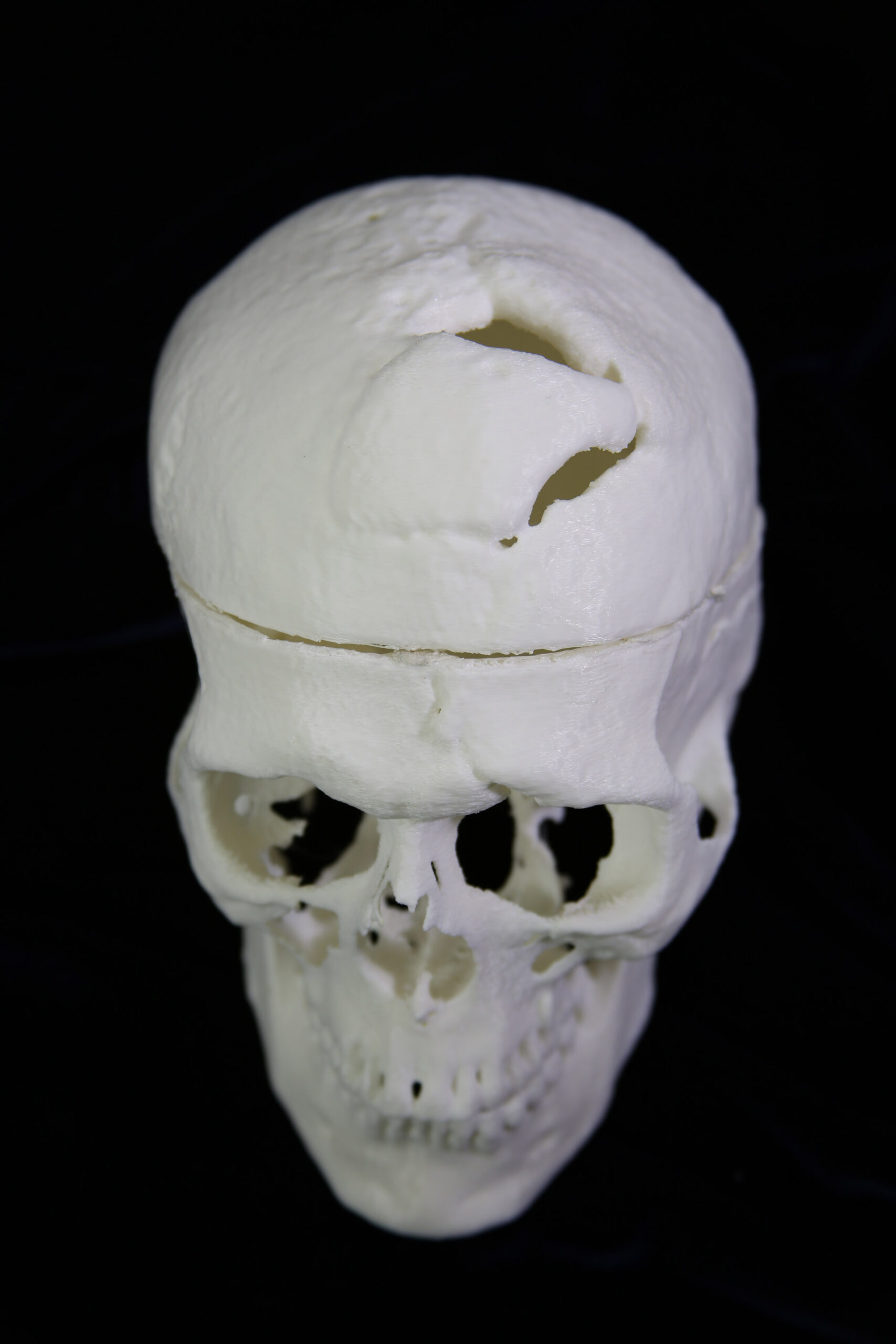

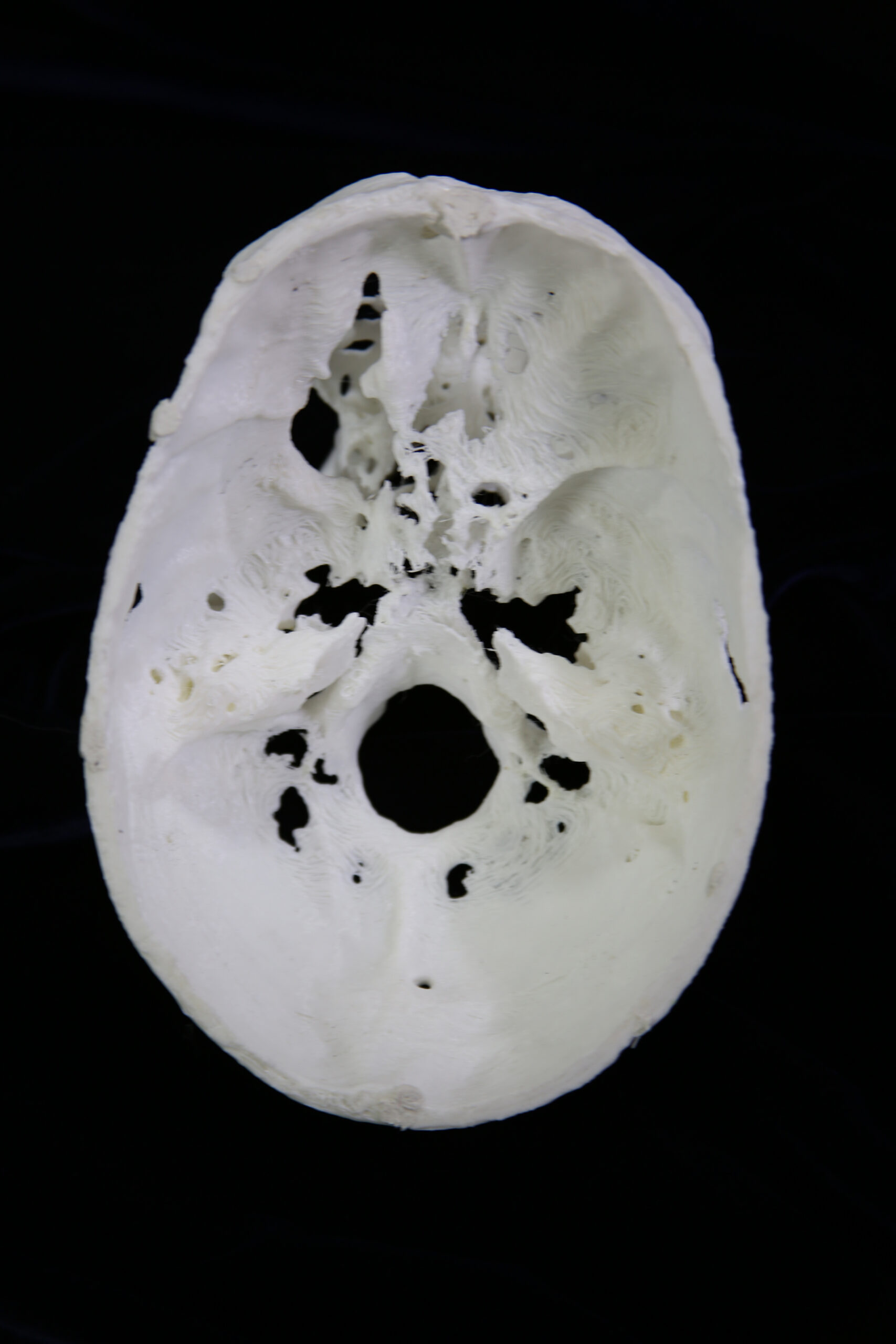

The pair began by 3D printing the skull of Phineas Gage, a 19th-century man who famously survived a traumatic brain injury after being impaled in the head by an iron rod. They chose Gage’s skull for its teaching usefulness, especially in the areas of neurological anatomy and the history of medicine, but also because the amount of existing public information about Gage made replicating his skull feel less invasive. In fact, a CT scan of his skull is available publicly online, and anyone can download a 3D model of it through the National Institutes of Health.

A 3D printed model of Phineas Gage’s skull, displaying the hole where the iron rod went through.

Beyond the Bone Box also will include a copy of the skull of Johann Gaspar Spurzheim, the chief proponent of phrenology, a now-discredited field of neuroscience that focused on studying the shapes of the skulls as a way to predict mental traits. Spurzheim died in Boston in 1832 and a public autopsy was performed. The brain researcher’s skull was significantly larger than average and was used in the 20th century as a case study in phrenology.

“A bone box is mostly about access,” Hall said. “With a collection that has human remains in it … education is critical to your existence. Otherwise this is just a strange horde that you never share, and ethically that’s irresponsible.”

Harrington and Hall hope eventually to begin circulating 3D-printed bone boxes within the Harvard Library system — a modern reimagining of Holmes’ vision.