When Gore was Widener

Stephanie Mitchell/Harvard Staff Photographer, courtesy of Harvard University Archives; video by Justin Saglio/Harvard Staff

Though razed, the legacy of Harvard’s original library has been kept alive in Cambridge’s official seal

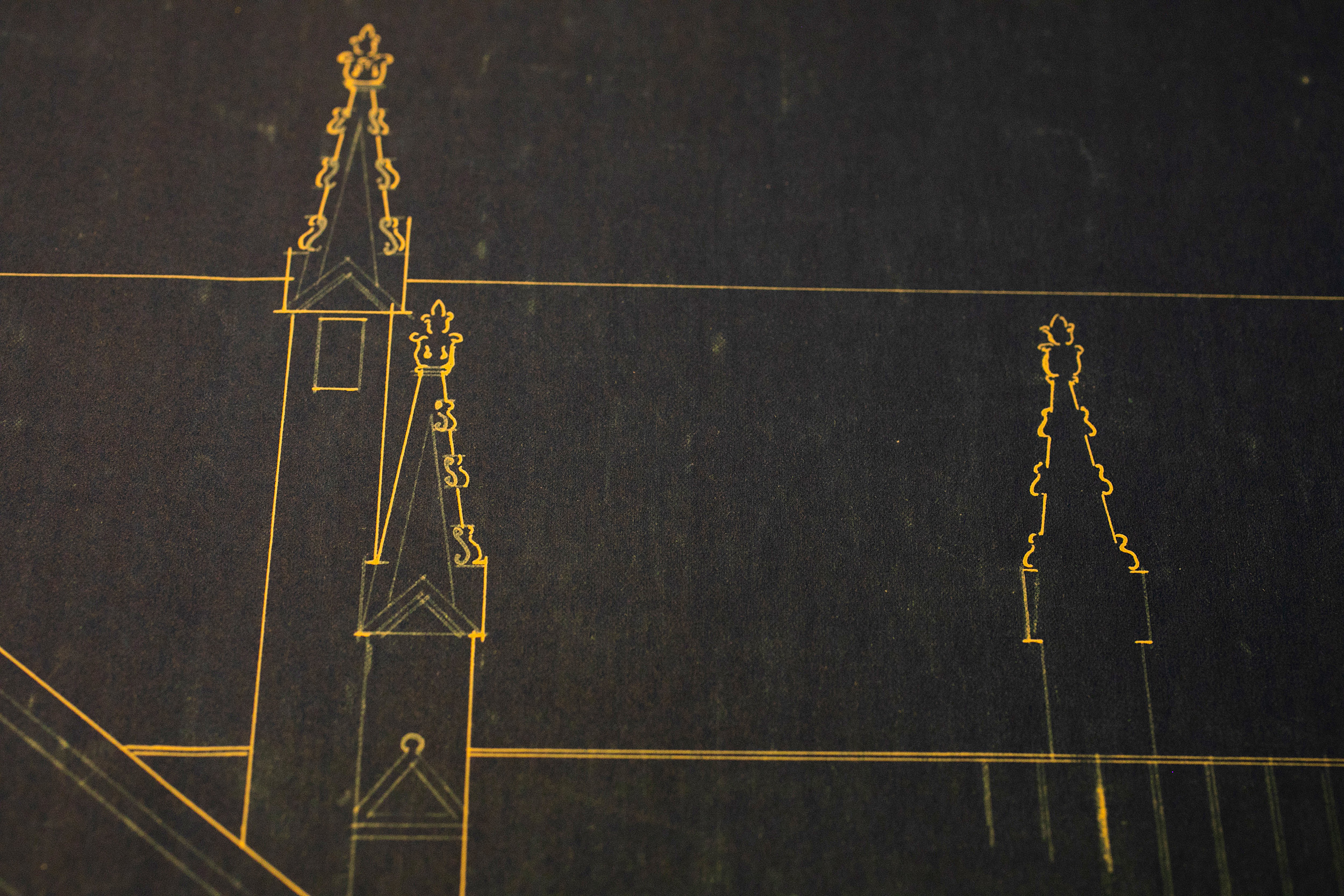

Two of the pinnacles from the old Gore Hall are preserved outside Widener Library.

Stephanie Mitchell/Harvard Staff Photographer

Before there was Widener Library, there was Gore Hall. The imposing Gothic Revival-style library occupied the same central spot in the Yard and in the lives of students through much of the 19th century and into the start of the 20th. It has now largely been forgotten on campus save for a plaque and two pinnacles at Widener, but the memory of Gore remains alive in the city of Cambridge — at least on its official seal.

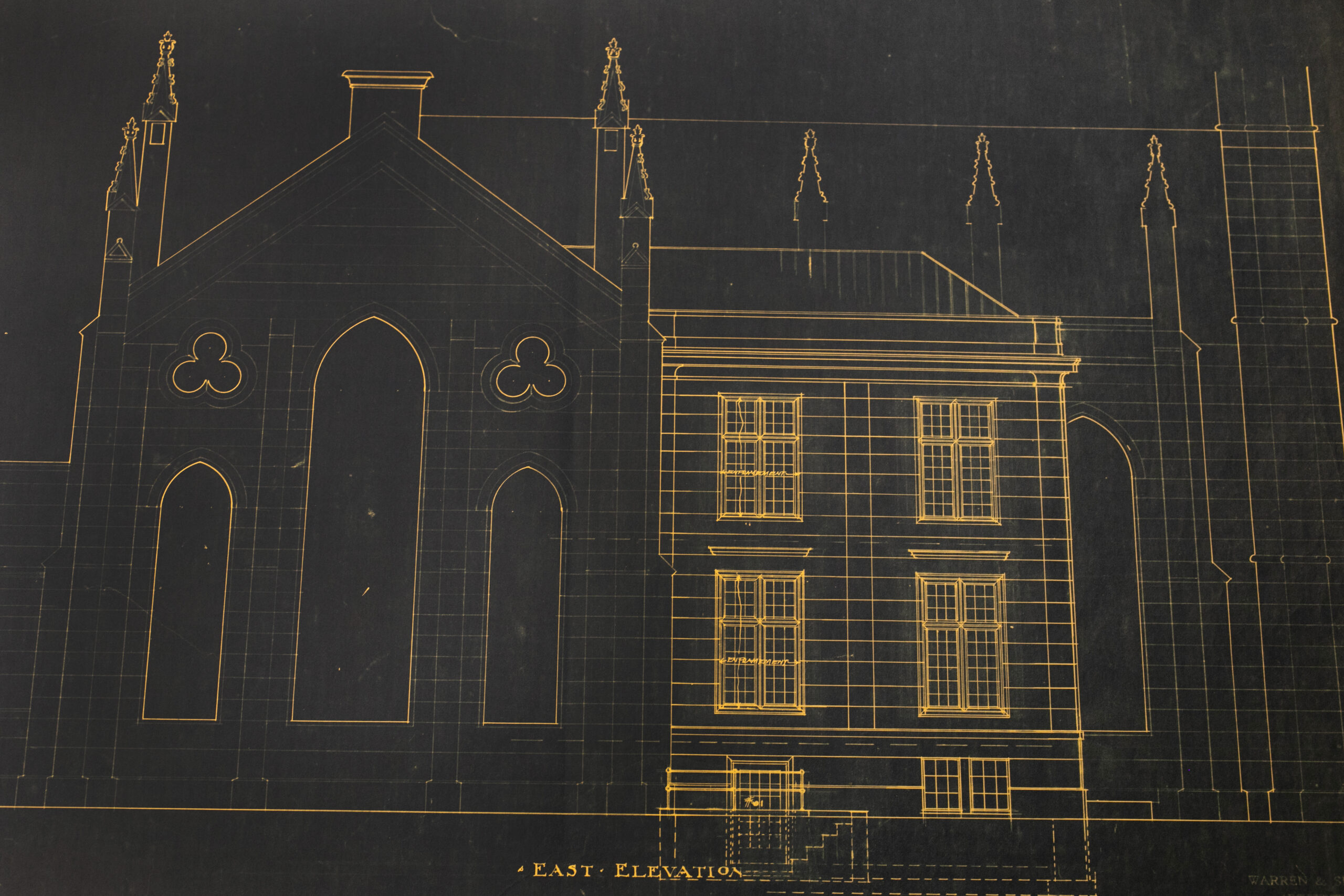

Built to be the University’s first separate library building, Gore looked more like a late-14th-century cathedral than a library. It had tall towers, curved columns, and pinnacles jutting skyward along the sides.

Photos by Stephanie Mitchell/Harvard Staff; archival images courtesy of Harvard University Archives

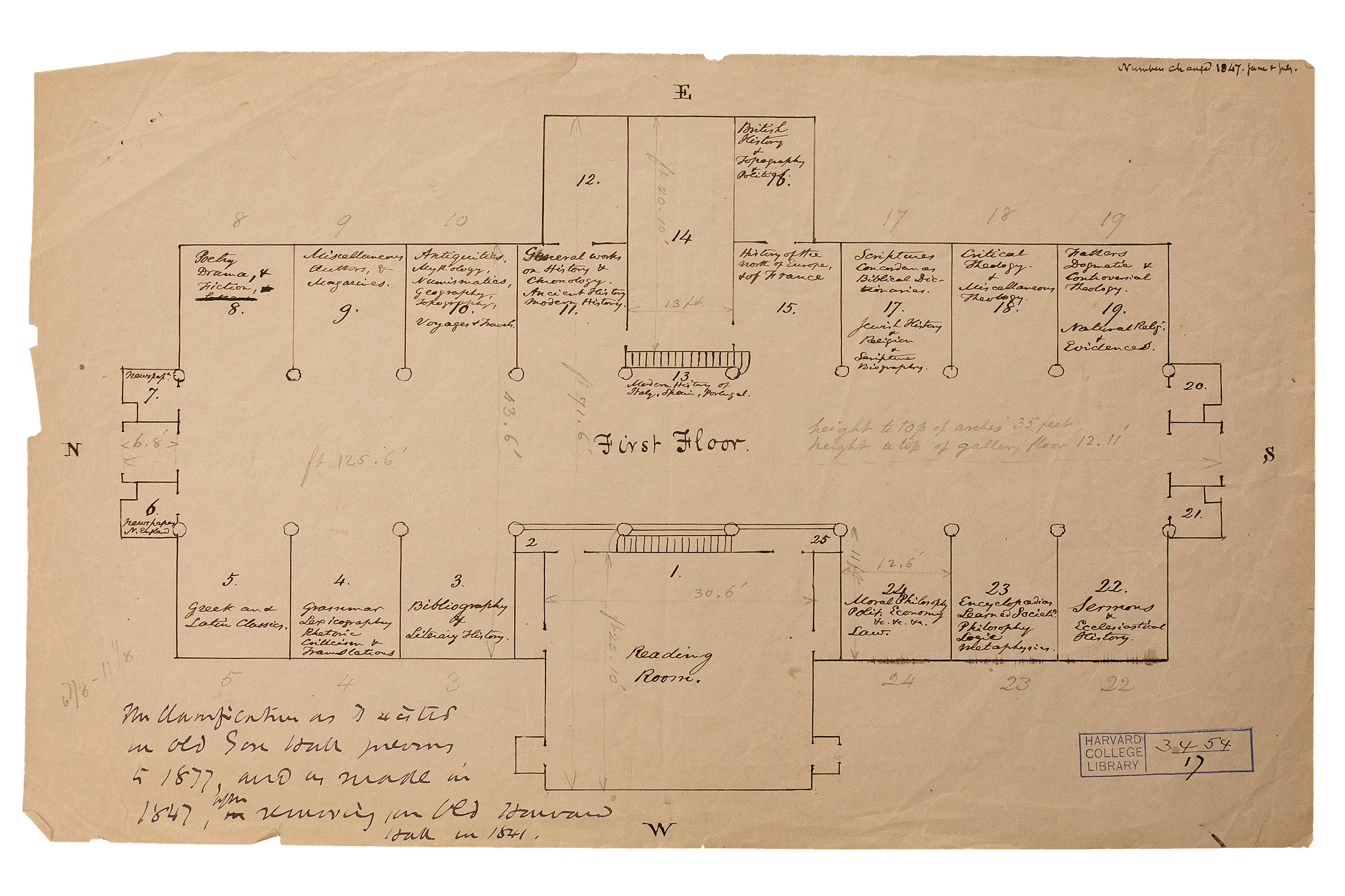

In the building plans, Gore Hall formed a Latin cross.

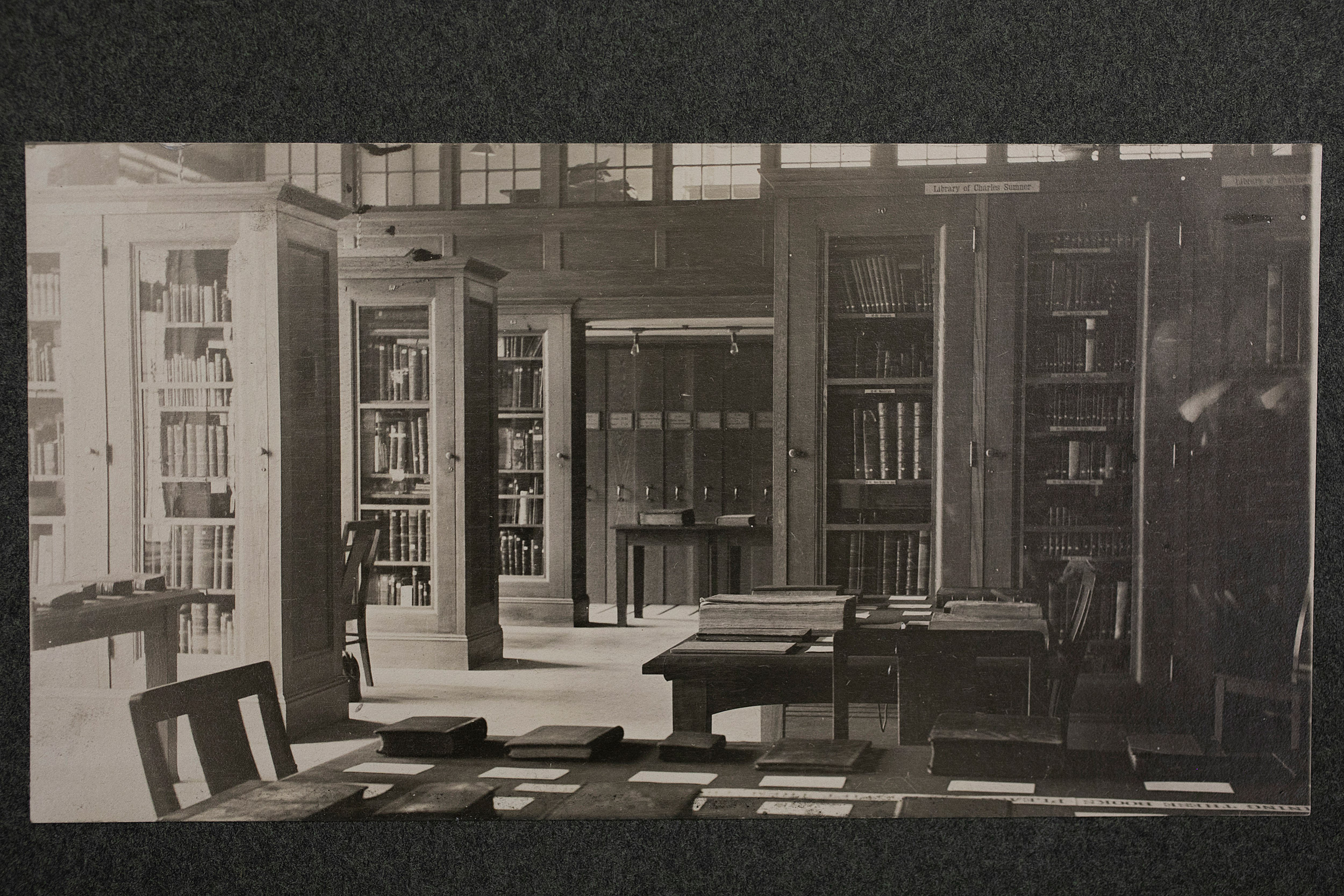

The interior was equally ornate and defined by a series of 10 columns rising from floor to ceiling with an open space that resembled the inside of a church. The books were placed in alcoves on the side to resemble the aisles of a chapel.

In his 1840 book, “The History of Harvard University,” Harvard President Josiah Quincy — who championed creation of the library — described how much of the exterior design was fashioned after King’s College Chapel at the University of Cambridge in England and that the entire structure was constructed using Quincy granite — the same stone used for the Bunker Hill Monument in Charlestown.

King’s College Chapel.

Photo via Wikimedia Commons

Designed by Boston architect Richard Bond, it was named in honor of former Massachusetts Governor and U.S. Senator Christopher Gore, a member of the Class of 1776 whose $100,000 bequest funded construction. Gore served in both the Massachusetts House of Representatives and Senate, and was one of the delegates at the 1788 Massachusetts Ratifying Convention that voted to adopt the U.S. Constitution. He was appointed the state’s first district attorney by George Washington and served as a member of the Harvard Corporation from 1812 to 1820.

The new library’s cornerstone was laid in 1838, and it officially opened in 1841 when the University’s growing collection of 40,000 books was moved in.

Gore was to be a landmark. In an 1841 article in the Boston Courier, editor J.T. Buckingham called it “a splendid edifice [that] will be an epoch in the History of the University, and the building itself will remain for ages a memorial of the public spirit and perseverance of President Quincy.”

In his historic account of the University, which was published while construction was still in progress, Quincy predicted something similar: “As none of the other Halls of the University present any claims to excellence in architecture, the attention of strangers will probably be directed to Gore Hall, when completed, as the principal ornament of the College square.”

It was true for quite some time. Gore was the central gathering place for processions on Commencement Day. It was where Harvard hosted several prominent dignitaries, including the Prince of Wales in 1860, and it celebrated its 250th anniversary there. Only five years after it opened, new Harvard President Edward Everett made the fateful decision to feature it as the central image in his design of the original seal of the city of Cambridge in 1846.

But Gore was not to be an edifice for the ages.

Image gallery

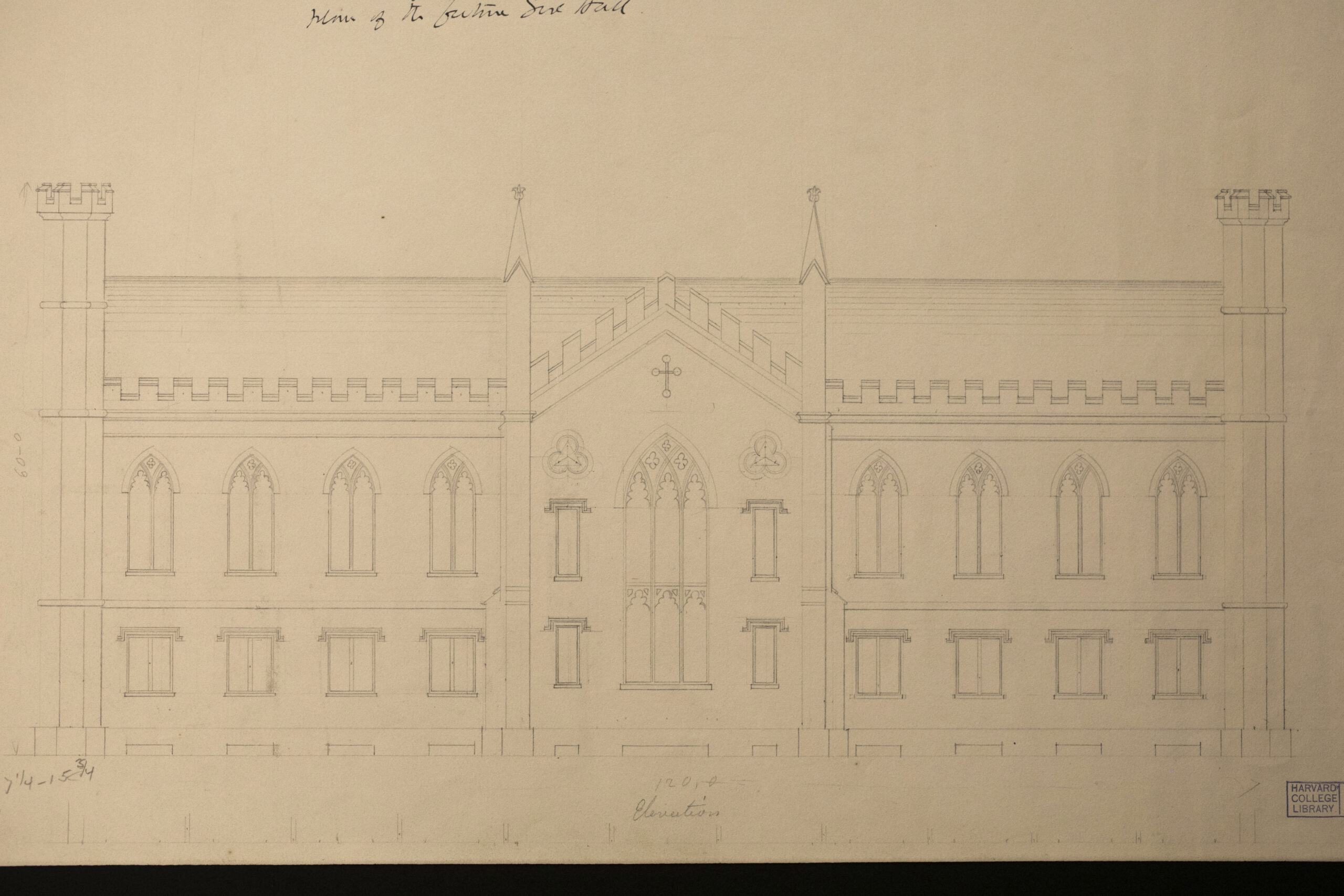

Harvard Archives holds photographs, drawings, objects, and memorabilia from Gore Library, the first dedicated library building at Harvard. Pictured here: An architectural drawing of Gore Hall shows the pinnacles. Stephanie Mitchell/Harvard Staff Photographer

Harvard Archives holds photographs, drawings, objects, and memorabilia from Gore Library, the first dedicated library building at Harvard. Pictured here: An architectural drawing of Gore Hall. Stephanie Mitchell/Harvard Staff Photographer

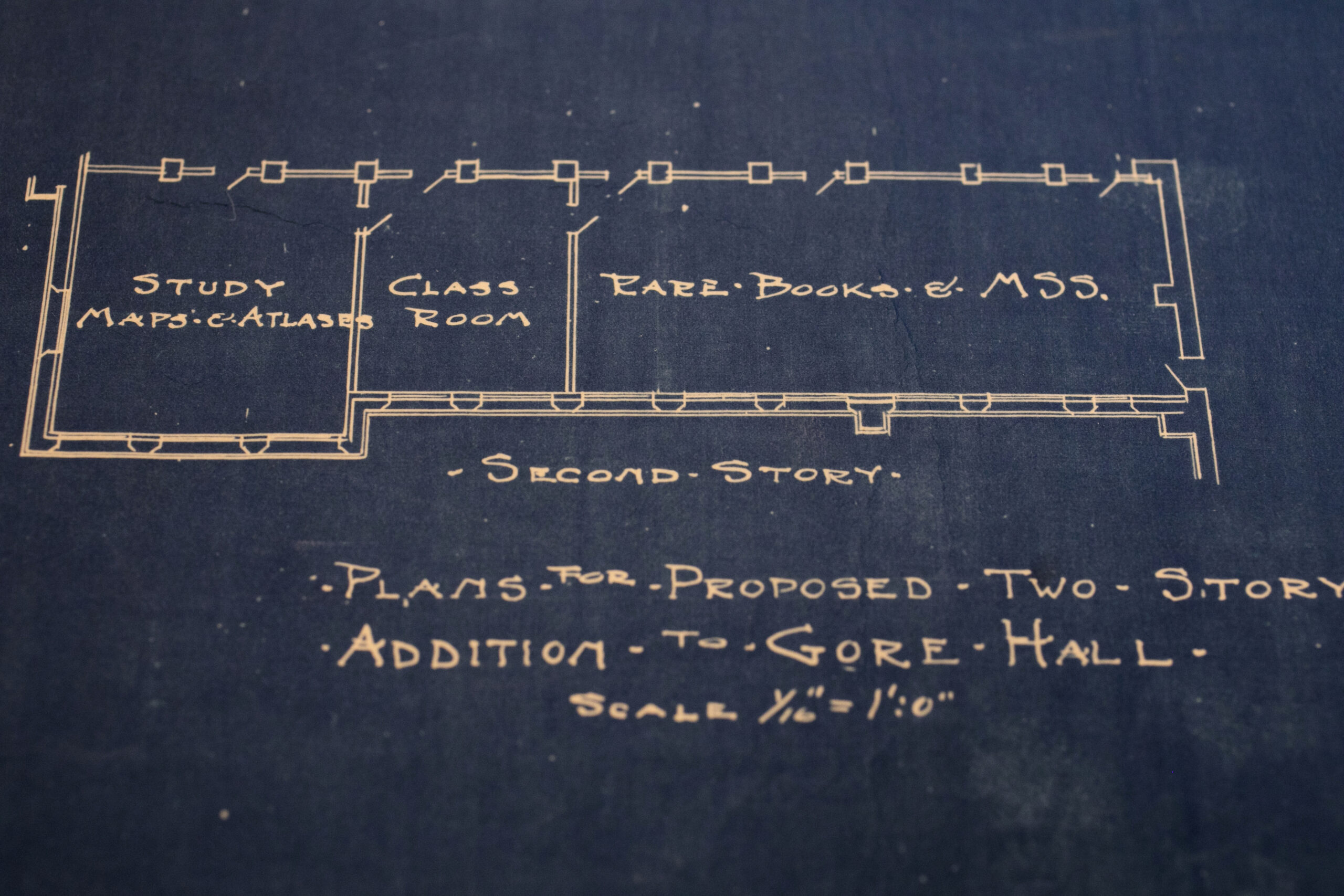

Harvard Archives holds photographs, drawings, objects, and memorabilia from Gore Library, the first dedicated library building at Harvard. Pictured here: An architectural drawing detail of the second floor of Gore Hall. Stephanie Mitchell/Harvard Staff Photographer

Harvard Archives holds photographs, drawings, objects, and memorabilia from Gore Library, the first dedicated library building at Harvard. Pictured here: An architectural drawing of Gore Hall. Stephanie Mitchell/Harvard Staff Photographer

Harvard Archives holds photographs, drawings, objects, and memorabilia from Gore Library, the first dedicated library building at Harvard. Pictured here: An architectural drawing of Gore Hall. Stephanie Mitchell/Harvard Staff Photographer

The flow of books to the library surged, owing to increased fund-raising and individual donations, and Gore Hall started filling up faster than expected. University leaders warned that more space would be needed and in 1875 the Harvard Corporation approved the addition of a new wing. By then books were being piled on the floor.

The addition, completed in 1877, gave the library space for 250,000 additional volumes, but it wasn’t enough. In 1895, the interior, once celebrated for its ornate beauty, was essentially gutted — the alcoves and the arched ceiling were lost — to make way for 250,000 more volumes and much-needed reading spaces.

Space wasn’t the only problem.

Students and professors complained in the winter that they had to wear their coats, hats, and gloves while doing research, since the hall’s sole furnace failed to adequately warm the entire building. It was also considered by many to be an eyesore inside and out, owing to the many renovations that had focused on practicality over aesthetics.

In 1907, Gore was expanded for the last time.

By then plans were underway to replace it. The only thing missing was the money. After receiving Eleanor Elkins Widener’s gift honoring her son, who perished with the Titanic in 1912, the University moved quickly to tear down Gore to make way for the Harry Elkins Widener Memorial Library. In August 1912, workers began moving the library’s 600,000 books. It took four months.

When Gore Hall was razed in 1913, its granite was used to build the foundations of Widener’s steps. Those foundations were excavated in 2002 during renovations.

Besides the plaque and the two pinnacles at Widener, four others were preserved and given to Francis R. Appleton, who was library chairman at the time. They are on display at Appleton Farms in Ipswich.

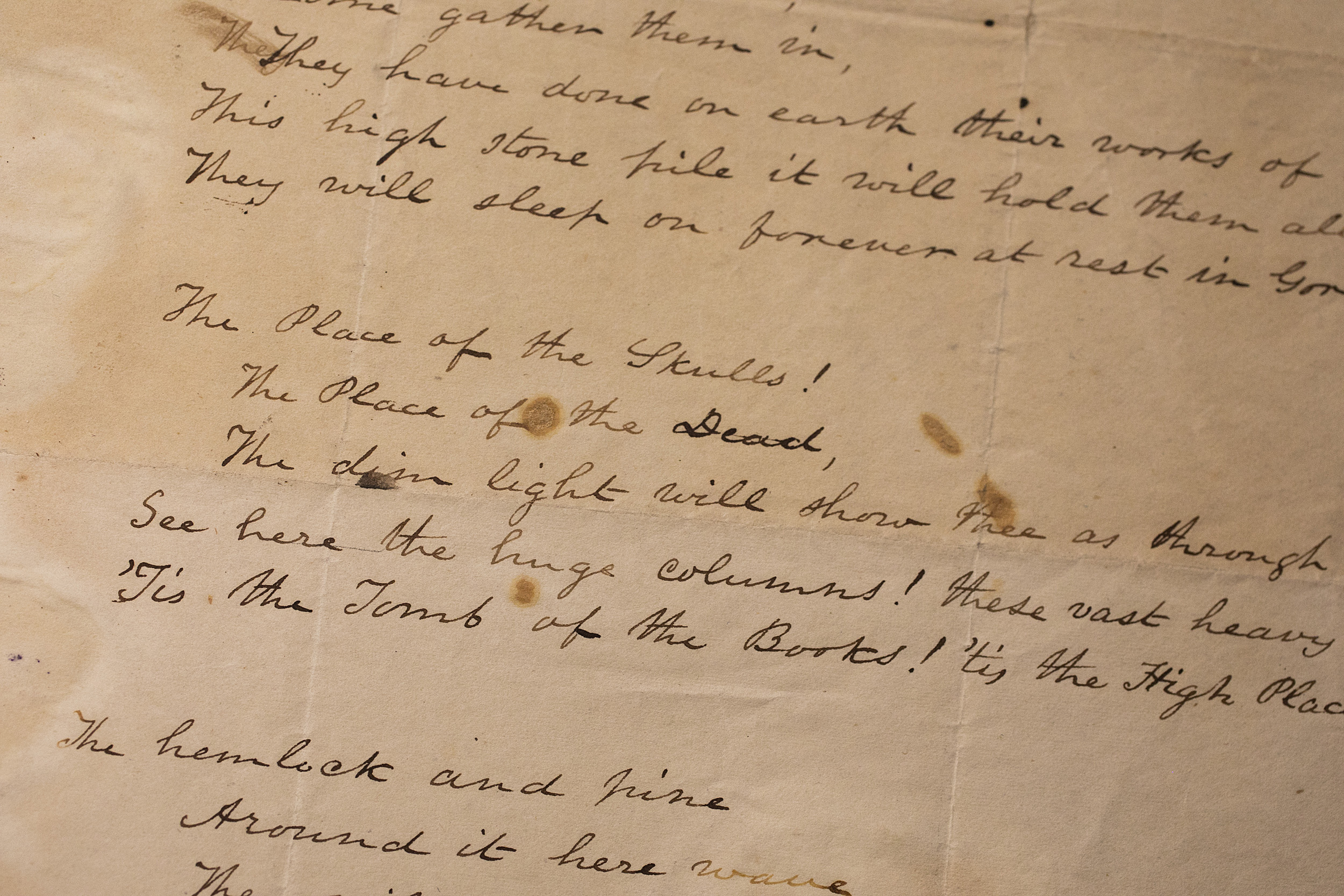

While the image of Gore can be found all over Cambridge, digging up fond personal memories of the place, which stood for a mere 72 years, requires archival research.

“I remember with the utmost satisfaction the many pleasant Sunday afternoon hours I spent in old Gore reading periodicals,” said Azariah Smith Root, Class of 1887, a former president of the American Library Association. He was one of almost 100 people who responded to a pamphlet head librarian William Coolidge Lane sent out in 1917 about the hall’s history.

“I know how much pleasure you must have in your new and convenient quarters,” Root wrote, “but to those of us who used the library at Gore Hall, that will always seem to be the Library of Harvard University.”