Professor Matthew Liebmann has done collaborative archaeological research with the Jemez tribe for almost two decades.

Stephanie Mitchell/Harvard Staff Photographer

Digging up the past

Archaeologist works with tribe to explore its history and to repair historic injustices

Archaeology Professor Matthew Liebmann has been collaborating with the Pueblo of Jemez in New Mexico for two decades, having served as tribal archaeologist and Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act program director for the Jemez Department of Natural Resources. Author of “Revolt: An Archaeological History of Pueblo Resistance and Revitalization in 17th Century New Mexico,” Liebmann took a group of undergraduate and graduate students to Jemez this summer to help members of the tribe excavate the site of two mission churches. Liebmann sat down with the Gazette to talk about his research, how his field has reckoned with the past, and how both influence his teaching.

Matthew Liebmann

Q&A

GAZETTE: What has been the focus of your research?

liebmann: I’ve been doing collaborative archaeological research with the Jemez tribe for almost 20 years. It started when I began my dissertation research in graduate school, and I’ve continued that relationship up to today. In the past we’ve looked at the Pueblo Revolt of 1680, the history of humans and forest fires in the Southwest, and ancestral Jemez relationships with the Valles Caldera National Preserve. Most recently, we’ve been excavating the remains of the earliest Catholic church on the Jemez reservation, established by Franciscan missionaries in 1622. All this research focuses primarily on the period of early European colonialism in the Southwest, and the ways in which Native Americans negotiated that colonization.

Analynn Toya of Jemez Pueblo, N.M., shows Harvard archaeologist Matt Liebmann broken pottery dating to the 17th century. The 10-year-old discovered the pieces near her grandmother’s home.

Courtesy of Matthew Liebmann

GAZETTE: Why is that period important?

liebmann: From an anthropological perspective, you can argue that the global changes that occurred after 1492 are on par with the other great hinge points of human history, alongside the origins of Homo sapiens and the agricultural revolution. But from a particularly American perspective, the stories we tell about Native Americans during this early “contact period” have direct impacts on the lives of indigenous people in the U.S. today. Federal law and Indian policy often draw explicitly on the notions of early American Indian history. Of course, the stories we tell about that time tend to be framed through the documents written by European men for European audiences. And those texts often cast indigenous people as inferior to Europeans, biologically, culturally, or technologically. All of those allegations are problematic for various reasons, yet they continue to be used to rationalize inequalities in modern American Indian life.

GAZETTE: Can you give an example?

liebmann: Sure, take Native American health. A few years ago we conducted a study of the population history of the Jemez people, focusing on the impact of diseases introduced after European contact. The results were surprising, but not for the reasons you might expect. We found that the Jemez were decimated after European colonization, with a population decline of 87 percent. That wasn’t the surprising part, of course. Most people are aware of the devastating impacts Old World diseases had on Native Americans. What surprised us was the timing. The data we collected revealed that population declines didn’t occur until nearly 100 years after the first contacts between pueblo people and Europeans [in the 1540s]. It was only after the establishment of Franciscan missions that diseases really took off. That leads us to ask why the population losses occurred when they did. The timing suggests that the crucial catalyst had to be more than simple exposure to new people and new germs. This suggests that pueblo people were not inherently vulnerable to disease. Rather, they were made vulnerable through European colonial policies of exploitation that led to poverty and malnutrition, rendering them more susceptible to disease.

For a long time researchers assumed Native American susceptibility to disease was inevitable, and the decimation that occurred after European contact was a historical event. One of the implications of our research is that this wasn’t a unique event. Health disparities have been a persistent reality for Native Americans from the 1600s to today. It was smallpox in the 1700s, tuberculosis in the 19th and 20th centuries, and it’s diabetes and cardiovascular disease today. Native Americans still suffer health inequalities at rates two to three times higher than the rest of the U.S. population. So if we tell stories about early European contacts that cast Native American susceptibility as natural or inevitable, we mask the ongoing health disparities that our society continues to inflict on American Indian people. On the other hand, if the archaeology shows that the scale of early disease outbreaks was affected directly by the policies of colonial governments, it makes us reexamine the facts underlying continuing Native health disparities today.

“My work with the tribe has always been not only in collaboration and consultation, but strives to work for tribal interests, instead of just my own academic interests.”

GAZETTE: How does that inform your latest research?

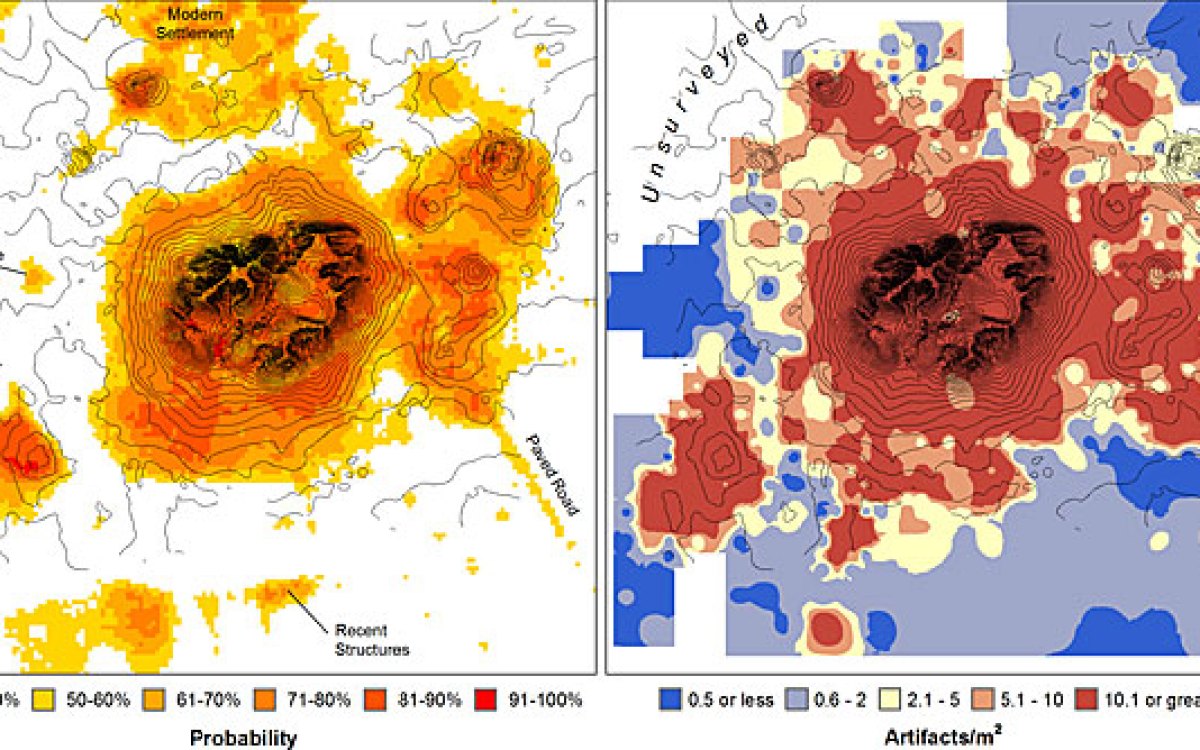

liebmann: Well, it was a logical extension of the population research to try to investigate the establishment of mission churches. The problem was we weren’t exactly sure where the earliest church was located at the pueblo. A map of the village from the 1920s includes a reference to “ruins of the old church,” but it wasn’t very specific. There are oral traditions among tribal elders that identify the general location of an old church, but no one knew exactly where that building was located, how big it was, or the date it was constructed.

Then a couple of years ago some routine road maintenance on the dirt roads in the village exposed a section of a church floor. My collaborator, Chris Toya, the tribal archaeologist at Jemez, suggested that we investigate that area before the site got damaged any further. The Tribal Council agreed that it needed to be studied and preserved, so they approved an excavation.

Our dig this summer exposed the architectural footprint of the church. Luckily there ended up being a lot more intact than we had originally anticipated. In fact, we found that there were actually two churches located in that area. The original mission church, which was established in 1622, is buried about one meter below the ground surface. That church was eventually destroyed, probably in the Pueblo Revolt of 1680. We found a layer of charcoal above the floor, most likely a result of the roof having been burned. Then a second church was built on top of that one in 1695. In archaeology, we often deal in millennia or centuries, or if you’re really lucky within a few decades. Here we have it down to within exact years. In part that’s because preservation in New Mexico is so fantastic. The climate is so dry, and the tribe is still living right around these remains, so the site has been protected from development over the years.

GAZETTE: So where do you go from here with the work?

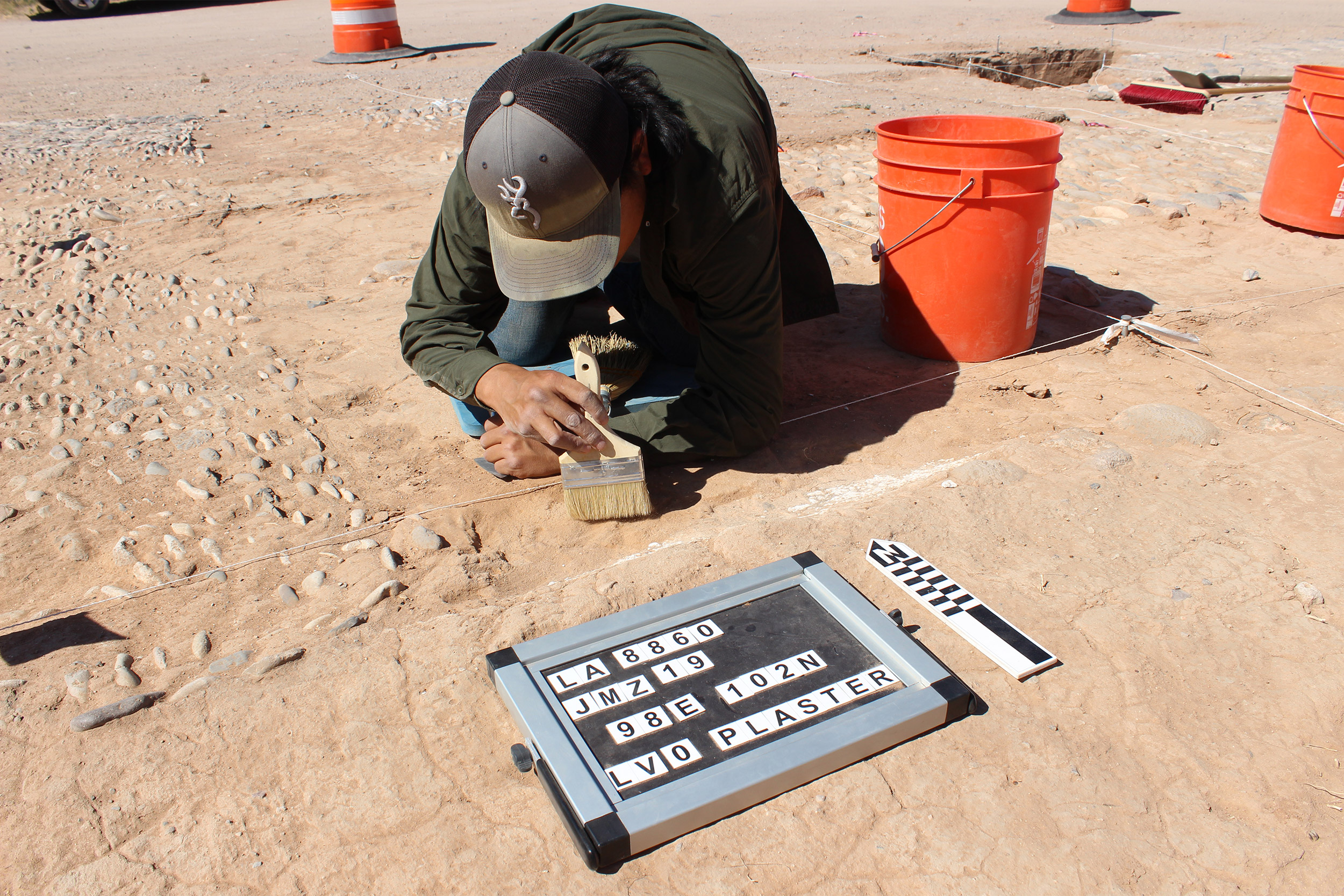

liebmann: We’ll make a presentation to the tribal council to review our initial findings, and we’ll see what they want to do to preserve the site. Our preliminary plans are to do a ground-penetrating radar study to try to locate other architectural remains around the church. Based on those results, we can do some targeted excavations to get a better idea of the impacts of the mission on pueblo life. We’re lucky to have the support of the Jemez Pueblo tribe on this project. This summer we were able to hire five tribal members to assist on the excavations, along with Harvard anthropology concentrators Nam Kim and Paul Tamburro. Two of my graduate students, Wade Campbell and Andrew Bair, worked on the site as well.

Harvard students and members of the Jemez tribe excavate the remains of the earliest Catholic church on the Jemez reservation.

Courtesy of Matthew Liebmann

GAZETTE: Given that it’s been a 20-year relationship, much of it must feel personal, even familial. But how do you see your role as a representative/voice for Harvard?

liebmann: The Jemez tribe itself has had a much longer relationship with Harvard that wasn’t always quite so rosy. It started back with the father of American archaeology, A.V. Kidder, who got his Ph.D. from Harvard in 1914. Kidder excavated a famous site called Pecos Pueblo, located east of Santa Fe, New Mexico. This work was groundbreaking for Southwestern archaeology. He established the pottery chronologies that archaeologists in the Southwest still use today.

Pecos Pueblo is historically related to Jemez. In 1838, the last inhabitants of Pecos migrated to Jemez and joined the Jemez tribe. When Kidder was doing his work in the early 1900s, he hired Jemez people to help him dig, and he commissioned an ethnography of Jemez. He excavated more than 2,000 graves at Pecos, and the remains were brought back here to the Peabody Museum. In 1999 under the National American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act, all of those individuals were transferred back to Jemez. The tribe reburied them at Pecos. So for most of the 20th century the relationship between Jemez and Harvard was pretty tense. But there was a healing that took place as a result of the Pecos repatriation. The Peabody Museum staff did a masterful job, and the tribe really wanted to continue their relationship after that.

Jemez has always valued having this continued relationship with Harvard. Many tribal members have visited Cambridge and have established relationships with Harvard faculty and staff. I started working with Jemez in 2000 after the Pecos repatriation had been completed. But I didn’t start working at Harvard until 2009.

I’ve always viewed my career as trying to help repair some of the damage done in the past by the archaeological community to Native American groups. So my work with the tribe has always been not only in collaboration and consultation, but strives to work for tribal interests, instead of just my own academic interests. There’s really been a significant shift in the relationship between archaeologists and tribes during the past 25 years, and this project is an example of the way archaeologists are starting to think about their research with the tribal interests being one of the primary motivating factors.

GAZETTE: How has that relationship framed what you teach in the classroom?

liebmann: This fall I’m teaching a Gen Ed class with Rowan Flad called “Can We Know Our Past? Archaeology’s Dirty Little Secrets.” The first part of the course showcases different methodologies that archaeologists use. It gives students insight into how archaeologists are able to say what we think we know about human life 300 years ago, 3,000 years ago, or even 300,000 years ago.The second half delves into the epistemology of archaeology. We encourage students to think critically about why we make the statements we do about the past and how much our own positions in contemporary society have informed the kinds of questions we ask about the past.

We also talk about the history of the discipline, and how we’re working much harder today to include voices that had been systematically excluded from the research process. There was a time in the past when archaeologists positioned themselves as objective, unbiased researchers who were simply measuring the archaeological record and reporting those results. Today there’s a much greater realization that where you start from makes a big difference in the kinds of questions you’re asking. It gets students to think about how the history of archaeology has affected our perceptions of the past today, and what we can do in the future to try to develop more nuanced and textured interpretations. We’re trying to get students to think critically about the statements we make about the past, what affects those statements, and what counts as knowledge.

Interview was edited for clarity and condensed.