Walter Sedgwick stands with the sculpture he gifted to Harvard Art Museums.

Photo by Susan Young Photography

Reunited with a ‘transcendent’ figure

Walter C. Sedgwick can’t remember a time without ‘Prince Shōtoku at Age Two’ in his life

Walter Sedgwick ’69 grew up visiting the sculpture every summer at his grandparents’ home, Long Hill, in Beverly, Mass. He felt a special connection to “Prince Shōtoku,” even from a young age.

“He was a figure of great reverence — very mysterious in a way, transcendent,” said Sedgwick, “but also tangible in other ways because of his baby-like form.” Sedgwick’s grandfather, Atlantic Monthly owner-editor Ellery Sedgwick, acquired “Prince Shōtoku” during a trip to Japan in 1936.

Recently, Walter Sedgwick has made the extraordinary gesture of gifting the sculpture to the Harvard Art Museums, in memory of Ellery Sedgwick Sr. and Ellery Sedgwick Jr., ensuring that it will be available for study and appreciation for generations to come. The sculpture is the subject of the new exhibition Prince Shōtoku: The Secrets Within (on view through Aug. 11).

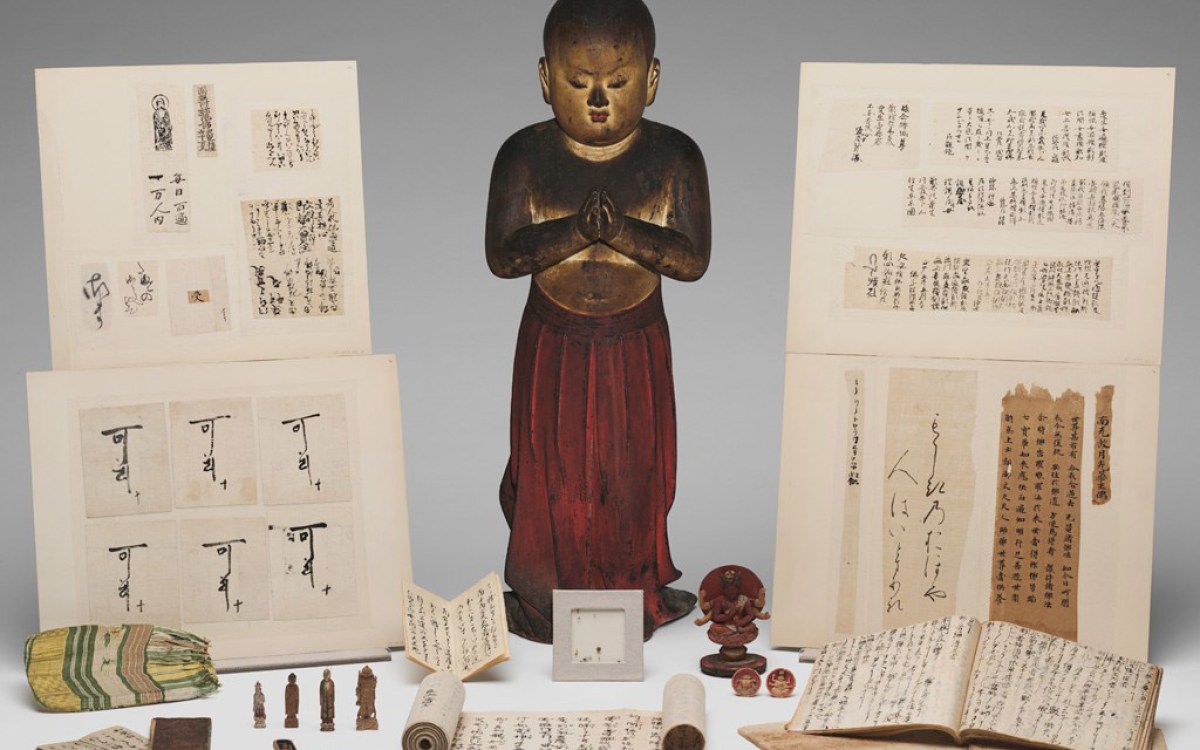

Made of Japanese cypress with inlaid rock crystal eyes, the sculpture depicts Shōtoku Taishi, who is believed to be the founder of Buddhism in Japan. At the age of 2 (1 by the Western count), Prince Shōtoku is said to have faced east, praised the Buddha, and manifested a relic between his hands; the sculpture depicts that moment. Dating to approximately 1292, the “Sedgwick Shōtoku” is widely recognized as the world’s oldest and finest surviving representation of Prince Shōtoku at age 2.

“Prince Shōtoku” is life-size and lifelike in the way it portrays the young child, complete with a large head, smooth skin, and the chubbiness typical of a baby. “When you are close to him, he has a living presence,” said Rachel Saunders, the Abby Aldrich Rockefeller Associate Curator of Asian Art, who curated the Prince Shōtoku exhibition. “This is something you sense even if you don’t know anything about Japanese Buddhist sculpture or Prince Shōtoku.”

Ellery Sedgwick displayed “Prince Shōtoku” in a Japanese shrine at Long Hill. And even though Walter Sedgwick said he and his siblings knew never to touch the sculpture, “Shōtoku was sort of a presence emanating from within the shrine — it was quite magical.”

Sparking curiosity

“Prince Shōtoku” kept company at Long Hill with oil paintings, ceramics, and centuries-old, hand-painted wallpaper. As he grew older, Sedgwick’s grandmother, Marjorie Russell, would take him around the house, answering his questions about each object. “Prince Shōtoku,” however, was generally acknowledged by Sedgwick and his siblings to be “the magnet” within the house, and was “the object I had the closest relationship with,” he said. “So, piece by piece, I learned about Shōtoku.”

Sedgwick also learned of a comprehensive 1968 article about the sculpture, written by Harvard professor and curator John Rosenfield. This scholarship not only elucidated some of the crucial historical background of the sculpture, but also detailed the 1937 discovery at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, of more than 70 dedicatory objects sealed inside the object. Marjorie introduced Sedgwick to Rosenfield, kicking off a relationship that left “a huge impression on me,” he said.

A photograph of Walter Sedgwick’s grandfather, Ellery Sedgwick, at Long Hill.

Photo by Katie Aberbach

In addition to taking some of Rosenfield’s classes, Sedgwick turned to him as a mentor. “He took me under his wing, and that’s why my interest in Asia grew so rapidly,” Sedgwick said. “He’d take you into the library and you’d go one-on-one [researching a specific question]. What more could you ask for?”

Sedgwick pursued his passion for Japanese art after Harvard, living in Japan for six months and then launching a store in Cambridge dedicated to Asian books. Although his professional life eventually took a different direction, “an interest in Asian art and culture has always been with me,” he said.

A figure to rally around

Sedgwick returned to Harvard in late May for the opening of Prince Shōtoku: The Secrets Within, where he watched as “Prince Shōtoku” did what he seems to do best: bringing people together. Specialists in various disciplines, from across Harvard and around the world, have studied the sculpture, and some of their latest findings were revealed in a public lecture by exhibition curator Rachel Saunders and Angela Chang, assistant director of the Straus Center for Conservation and Technical Studies.

“In a sense, I see him as an ambassador to the world — for all the other sculptures and works of art” that are not as accessible for study, Sedgwick said. “But I think he would have wanted to be studied,” he added with a laugh. “Prince Shōtoku really is an ambassador, and an inheritance of humanity.”