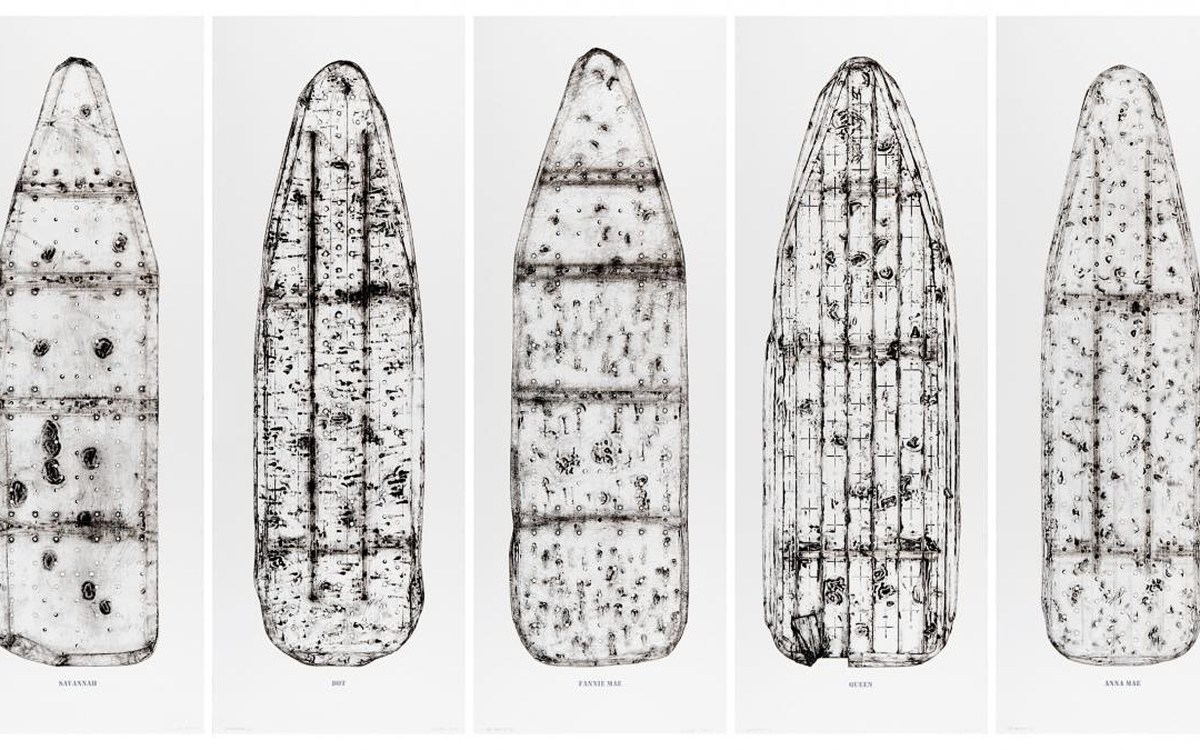

A new pairing on a second-floor wall overlooking the Harvard Art Museums’ courtyard has placed the work of contemporary artist Kerry James Marshall alongside that of 17th-century Dutch painter Nicolas Régnier.

Stephanie Mitchell/Harvard Staff Photographer

An unanticipated juxtaposition

Harvard Art Museum curators challenge expectations with new art pairing

When the Harvard Art Museums reopened in 2014 after an extensive renovation, its new design enabled curators to display art in novel ways, creating dynamic connections between the approximately 250,000 works in the collection.

That connective impulse informs a new pairing on a second-floor wall overlooking the museums’ courtyard, where the work of contemporary artist Kerry James Marshall was recently installed alongside that of 17th-century Flemish painter Nicolas Régnier.

Marshall’s untitled work from 2008 and Régnier’s “Self-Portrait with an Easel,” completed circa 1620, both depict an artist, palette in hand, gazing out at the viewer. But the differences in scale, tone, style, time period, and use of color render each painting a striking counterpoint to the other. “This combination really sets up a whole series of questions for visitors,” said Mary Schneider Enriquez, Houghton Associate Curator of Modern and Contemporary Art, who was part of the museum team responsible for selecting the works.

“The context is so different,” she said. “The role of that artist, how well we know him and what his painting was about, I think, begins to become a little more enigmatic than when it is hung by paintings from a similar period. Setting up that kind of dialogue opens up a discussion about so many things.”

Untitled work by Kerry James Marshall from 2008.

© President and Fellows of Harvard College

For Enriquez, hanging the work of Marshall, whose art is profoundly influenced by urban culture, the African American experience, and the Civil Rights Movement, beside that of Régnier, a Caravaggesque Baroque painter whose subjects include saints and figures from classical mythology, is a provocative move. It challenges viewers to think more deeply about past and present notions of the art form and the history of portraiture, she said, and reconsider long-held notions of “who the artist is, what the artist looks like, and what he or she is trying to convey.”

In Marshall’s piece, a black painter stares out from the canvas. Though his palette is brightly colored, his brush is dipped in the black paint located directly at the center of the work. The reference is unmistakable. The painting was inspired by a 1926 essay by Langston Hughes in which the author and poet wrote about the emergence of the black artist who was unafraid to fully embrace black culture in his or her work and abandon the “white is best” aesthetic.

“Self-Portrait with an Easel,” Nicolas Régnier, circa 1620.

© President and Fellows of Harvard College

Ensuring that the art on its walls speaks to all audiences is paramount to the Harvard Art Museums.

“A priority of ours is to try to change the dynamic of the past so our students and our visitors [from] all worlds can see the greats of the history of art then and now, and can think about the historical collections at many art museums from the perspective of who is represented and who is not,” said Enriquez.

“We felt it was important to give the Marshall painting real prominence both because of its visual power and because of the way that Marshall wants to challenge the story,” said Ethan Lasser, the Theodore E. Stebbins, Jr., Curator of American Art, who also helped with the selection. “I think it’s the power of challenging chronology and the power of a living artist who is not just looking to the past to get inspiration — he’s looking to the past as a place to challenge, as a place to insert himself.”

Ethan Lasser, the Theodore E. Stebbins Jr. Curator of American Art, and Mary Schneider Enriquez, Houghton Associate Curator of Modern and Contemporary Art, discuss Marshall’s work.

Kris Snibbe/Harvard Staff Photographer

Challenging assumptions has been central to Marshall’s practice.

“What I want to happen when I go to a museum is that expectations of what you find in there are completely altered,” he told a Harvard crowd during a campus talk in 2012, “so that it’s not commonplace to just see European paintings with European bodies, but it’s also as likely that you will see … black figures, Asian figures, or Hispanic figures.”

Similar in conception to Marshall’s work, Régnier’s self-portrait depicts the artist but also includes the subject he is painting. The picture represents a kind of turning point in which the artist “is showing himself at work, and thinking about the magic of painting. He wants us to see how good he is,” said Lasser.

The Baroque artist was also playing with perspective. Régnier appears to be looking at the person he is painting, which puts the viewer in the position of both observer and sitter. “That’s part of the magic of that painting that speaks across centuries,” said Lasser.

And, like Marshall’s piece, he continued, it’s “a painting always in the making.”