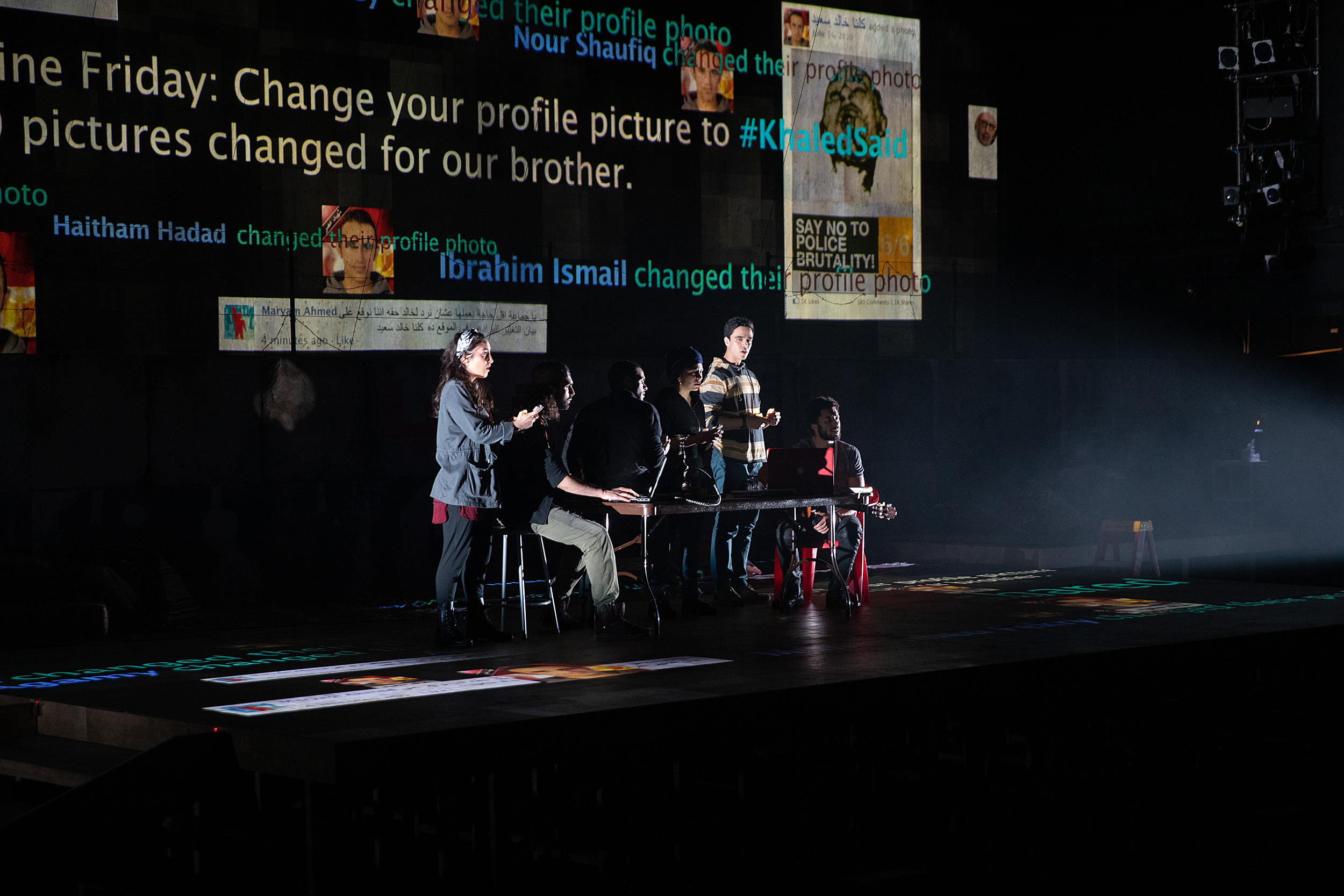

“We Live in Cairo” tells the story of coming of age during the 2011 uprising in Egypt and the age of social media.

Photo by Evgenia Eliseeva

A revolutionary musical

‘We Live in Cairo,’ about the 2011 Egyptian uprising, premieres at A.R.T.

Love. Music. Freedom. These are the universal themes at the heart of “We Live in Cairo,” a new musical by Daniel and Patrick Lazour, which is having its world premiere at the American Repertory Theater. Set during the January 25 Revolution, the 2011 uprising in Egypt, the work, under the music direction of Madeline Smith and music supervision of Michael Starobin, celebrates the hope and exuberance of the uprising, even as it acknowledges the turmoil that has followed.

The brainchild of the Lazours, brothers of Lebanese descent who began writing musicals together in their early teens, “We Live in Cairo” focuses on six young people at the heart of the protests that filled that city’s Tahrir Square with music and cries of “Bread, freedom, and social justice,” ultimately bringing down the regime of President Hosni Mubarak. As the production, which is directed by Taibi Magar and choreographed by Samar Haddad King, went into its final rehearsals, the Gazette sat down with the brothers and Tarek Masoud. Masoud, who served as a consultant on the project, is the Sultan of Oman Professor of International Relations at the Harvard Kennedy School and the son of Egyptian immigrants.

Masoud’s perspective is useful, say the brothers, because he provides a scholar’s frame of reference. He will speak after the 2 p.m. performance on June 1 as part of a series of post-show discussions called Act II.

Daniel Lazour said that when the project began in 2013, “We were just really taken with the jubilation of 2011.” He cited the rapid growth of the uprising, which drew “a million people in Tahrir Square during the 18 days” of protest.

Like those protesters, the brothers were enthralled by the possibilities of the Arab Spring, which had begun a month earlier in Tunisia. “These characters are dealing with hopes and dreams about a secular government and a government of democracy, a government where they can express themselves fully and freely,” said Patrick Lazour. In this context, he said, a musical made perfect sense. “This revolution was truly a moment for the artists of Egypt and to express themselves.”

“That’s where the narrative sort of ended for our first draft,” said Daniel. “We were like, isn’t this great? As things started unfolding post-revolution, we realized that the story needed to encapsulate that as well.”

Understanding the aftermath — in which current Egyptian President Abdel Fattah el-Sisi has consolidated power through the military — was problematic. Although the brothers were able to workshop their musical at the American University in Cairo a year and a half ago, for example, what they heard varied greatly, depending on the age of the respondents. “Some were old enough to have been there,” recalled Patrick. Other students, who had been too young to be directly involved, were “sort of seeing it through a different lens,” he said.

His brother summed up the experience: “There’s no historical record to agree upon because there isn’t a historical record that’s allowed to exist.”

“There is an enormous amount of disagreement about what the January 25 Revolution really was and who owns it,” said Masoud, the co-author of “The Arab Spring: Pathways of Repression and Reform.”

“If you were to open up the constitution of Egypt, that is today being amended in order to allow Egypt’s current president to persist in office until 2030, you would see encomia to the January 25 Revolution — even though many people would view the current regime as being the exact opposite of what the January 25 Revolution was about.”

For example, although the protesters sought the end of repressive state controls, Masoud points out, “You will see often military officers or police officers with ribbons commemorating the January 25 Revolution.

“This is an event in Egypt that everybody has agreed is legitimate. But everybody uses [it] for their own ends.”

The cast of “We Live in Cairo” perform onstage as an ensemble; Jakeim Hart performs a musical number.

Photos by Evgenia Eliseeva

Overall, the professor praises the playwrights for their success in depicting such a complex situation. “They got all the important things right,” said Masoud, an unabashed fan of musicals. In particular, he cites “the incredible spirit of possibility that attended the revolution.”

“You’ve got to remember Egypt was a place that everybody thought was totally stagnant,” he said. “So when [the revolution] did happen, our jaws just dropped. It was indescribably inspiring.”

Although subsequent events have been dispiriting, with el-Sisi’s regime assuming many characteristics of Mubarak’s, Masoud credits the brothers with reviving that earlier sense of optimism. “I had gotten quite jaded about the revolution,” he recalled. “Hearing their music I have all those feelings once again. So they were able to somehow capture that spirit of possibility and make me remember it. To me, that is the most amazing thing about this play.”

“And that’s what ‘We Live in Cairo’ reminds us of as well,” said Daniel Lazour. “By helping us recapture that moment of potential, it reminds us that none of that stuff went away. Those people are still around. These yearnings are universal — yearnings that got people to risk their lives and livelihoods in order to demand something better. That’s still there. That didn’t go away. And so that possibility that existed may still exist. And if you leave the theater with just that thought, I think that’s pretty remarkable.”

American Repertory Theater (A.R.T.) at Harvard University, the Ash Center for Democratic Governance and Innovation, and the Belfer Center’s Middle East Initiative at Harvard Kennedy School will co-present the Act II Speaker Series, discussions with leading artists, journalists, and scholars in conjunction with A.R.T.’s production of “We Live in Cairo” on topics inspired by the show. The show runs until June 23.