How much would you pay for a masterpiece?

Patrons view a shredded Banksy painting at Museum Frieder Burda in Germany.

AP photo

Harvard experts discuss the rising costs of competing in the fine art market

Last October, seconds after it sold at Sotheby’s in London for $1.4 million, Banksy’s “Girl With Balloon” self-destructed as a shredder hidden in the picture’s frame began grinding up the image from inside. It was a perfectly timed trick by the reclusive graffiti artist, who immediately posted a video about his art punk online and renamed the piece “Love Is in the Bin.”

Onlookers were stunned. Later, an auction house official said in a statement what was by then likely obvious to everyone: “It appears we just got Banksy-ed.”

Harvard’s Mary Schneider Enriquez wasn’t surprised.

“I think this showed his control and manipulation of us in the most brilliant manner possible,” said Enriquez, Houghton Associate Curator of Modern and Contemporary Art at the Harvard Art Museums. “He took his practice a step further in the sanctity of this heated auction house market and said, ‘Look at what I’ve done to you.’”

Experts agree that the ruined image by the anonymous artist with a flair for the dramatic and for tagging prominent buildings and landmarks with his politically charged satirical works may well be worth more now in its partially shredded state (the shredder stalled halfway through the job). Some even think the prank may have doubled the picture’s price. But how did the work of this street artist turned trickster and gallery darling become so valuable in the first place? For many, the answer involves mystique. Banksy is renowned as much for his antics and anonymity as for his art, they say. His skill, combined with his secret identity and the stealth surrounding his practice, have helped fuel his reputation and the interest of the art world.

“His trick makes [the piece] more valuable. It makes me chuckle and also recognize there’s an absurdity to this art world right now that’s both painful and ridiculous.”

Harvard Art Museums’ Mary Schneider Enriquez on Banksy’s ‘Girl With Balloon’

“At some level Banksy’s work originally had been about doing hidden graffiti, and he’s incredibly talented. Then there is the phenomenon of who he is. The mystery plays into this whole idea of the genius of the artist,” said Enriquez. “This to me seems like the perfect game he played on some level,” she added of his Sotheby’s stunt. “The flip side of that is because the market is the way it is, his trick makes [the piece] more valuable. It makes me chuckle and also recognize there’s an absurdity to this art world right now that’s both painful and ridiculous.”

If Banksy’s “ruined” work were to come back on the market, it could fetch a figure close to $3 million — but it still sits at the low end of the stratospheric art market scale. Works from old masters to contemporary hands and even a painting by a living artist have set a steady stream of record-breaking sales in recent months. In November, Edward Hopper’s 1929 painting “Chop Suey” sold for $91.9 million at Christie’s auction house. Two days later, David Hockney’s 1972 “Portrait of an Artist (Pool with Two Figures”) sold for $90.3 million, the highest amount ever paid for a work by a living artist. In November 2017, Leonardo da Vinci’s “Salvator Mundi,” or “Savior of the World,” a portrait of Christ dating to about 1500, fetched a record-smashing $450.3 million.

To get at exactly how the market drives up such numbers, the Gazette spoke with some experts in the field.

A historic perspective

When considering the value of a work of art, factors such as rarity, quality, condition, and provenance all play a role. A piece such as “Salvator Mundi” commands a high price tag because it is both unique and the product of an artist universally considered a truly great master. But the question of who formerly owned a painting is also important to its final price tag, said Soyoung Lee, the chief curator at the Harvard Art Museums. The fame or reputation of a previous owner can often elevate an artwork’s worth, she said, inspire more interest in the piece, and help confirm its authenticity.

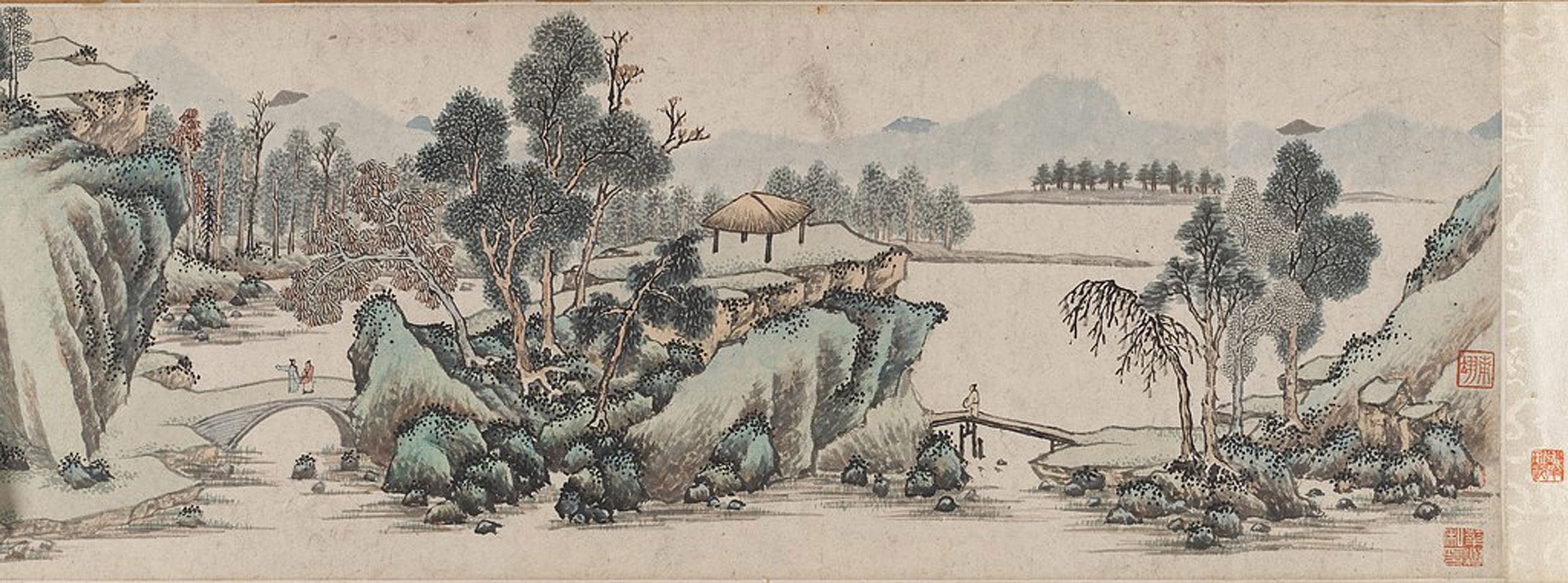

Today, celebrity owners regularly generate buzz in the market when they sell art from their collections. The chance for a buyer to know they hold some direct connection to the rich and famous can be a powerful driver. For a historic perspective on that trend Lee, a former curator of Asian art at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, looked to China and its imperial court, where the value of a painting or scroll often had as much to do with whom it may have belonged to as with its quality. And those previous owners, Lee noted, weren’t shy about adding their own flourish to a great work.

“In the Western tradition the idea that somebody other than the artist would mark the painting is blasphemy. That would ruin the value of the art,” she said. “But with Chinese painting — scrolls, for example — if produced for the emperor, it would have his seal right on the painting,” augmenting its value. Over time, she explained, as the work traded hands, subsequent owners — often artists or critics of note — would add their own seals directly onto the piece.

“The more marks you accumulated and the more you accumulated of people of worthy names,” Lee said, “the more the value of that painting increased.”

“Landscape with Mountain Village” by Wen Zhengming is marked with the seals of previous owners.

© President and Fellows of Harvard College

“It was radical at the time. Now it is the most traditional, the most beloved type of art that is just an automatic draw,” says curator Soyoung Lee about Impressionist works by Pierre-Auguste Renoir and Claude Monet.

© President and Fellows of Harvard College

Today, knowing where a painting came from can boost its worth and help assure interested buyers that the transaction is lawful. “It’s important for museums to know that the work was collected or exchanged hands legally,” said Lee. “That’s a big issue and in a sense elevates the value of a work for a museum when considering acquisition.”

Some prices turn on whimsy or personal preference. Often the value of art rises and falls depending on the public’s changing tastes, or the likes and dislikes of the critics and experts who judge artworks. When the Impressionists broke from tradition in the 1800s, turning from realism to a more undefined technique that used vivid colors and rougher brush strokes to capture light and movement on the canvas, some in the art establishment were elated; others were appalled. Today a work by Claude Monet or Pierre-Auguste Renoir commands the highest prices.

“It was radical at the time,” said Lee. “Now it is the most traditional, the most beloved type of art that is just an automatic draw. That often happens with artists who are trailblazers.”

On the auction block

The skyrocketing art market is a boon for auction houses and those with the means to buy and sell such expensive works. But for most — including museums — those weighty price tags can mean limited direct access to masterpieces.

“You go into an auction with a limit and there’s no way you can win if somebody else comes in willing to go higher,” said Lee. “And with these trends of catastrophic prices, museums really have been shut out of auctions. It’s unfortunate because most of these individuals will not be showing these works for the benefit of the public.”

However, not every collector is intent on taking masterpieces out of public view. “Just because someone is buying art and putting it in storage doesn’t mean they are just simply interested in selling or trading it as a financial asset,” said Mark Diker ’88, M.B.A. ’96, founder, managing partner and CEO of Diker Management LLC, who is also a longtime collector. Donations from Diker and his parents, Chuck Diker ’56, M.B.A. ’58, and his wife, Valerie, support the Diker Gallery, an exhibition space on the Harvard Art Museums’ first floor devoted to mid-century abstract works. “Many owners are creating private museums where the public can come and enjoy their collections,” he added.

“Many owners are creating private museums where the public can come and enjoy their collections.”

Mark Diker ’88, M.B.A. ’96

Diker family donations support a Harvard Art Museums’ exhibition space devoted to mid-century abstract works such as Frank Stella’s “Red River Valley” and Jackson Pollock’s “No. 2.”

Image courtesy of Harvard Art Museums

Collectors who use their expert eye and their passion to amass art that others will see include Mitchell Rales, the billionaire investor who opened the private museum Glenstone in 2008 in Potomac, Maryland. The Menil Collection in Houston houses the once-private holdings of its founders, the art collectors and patrons John and Dominique de Menil. California’s J. Paul Getty Museum was founded by its namesake art enthusiast and businessman, who established a museum trust “for the diffusion of artistic and general knowledge.” J. Tomilson Hill is the billionaire behind a new arts-focused development in Hong Kong and a private museum that recently opened in the Chelsea neighborhood of New York City.

Still, the soaring prices at auctions have left most museums behind.

“They don’t have the resources to buy some of these incredible artists at the prices they are now demanding. And that means that the needs we want to fill — and that many museums need to fill — is a serious challenge,” said Enriquez. “It means that you raise money or may receive important works as gifts from your gracious and wonderfully generous donors, but it adds a level of uncertainty and complication to what a museum can have in their collection.”

Yet the auctions themselves can be a time to glimpse a masterpiece, said Lee, who encourages those interested to attend preview weeks at Sotheby’s or Christie’s where such works are often exhibited to the public before going on sale. The auction’s day sales — as opposed to the evening events, which are typically reserved for the works in higher demand by the more famous artists — often feature less-expensive pieces that are within reach of first-time buyers on a budget.

“There are auctions of all kinds of art and many things are actually quite affordable,” said Lee. “It’s a kind of open-to-all, fun experience that really lets people see great master works and even dabble in buying.”

Wealth, globalization, and technology

The jump in the number of U.S. and European billionaires over the past several decades and the success of emerging markets has introduced new players to the high-stakes world of fine art collecting and driven prices up. In the past, big buyers typically hailed from the U.S. and Europe, said Diker, but as Chinese and Russian wealth has grown so too has the number of super-rich from those countries who are interested in art for its aesthetic appeal and its worth as an alternative “real” asset that can retain or even increase its value.

“For someone to buy one painting for $50 million I would think their net worth has to be at over $1 billion,” said Diker. “Thirty years ago, there were just over 100 billionaires in the world. Today there are over 2,200 who can spend that amount.” Beyond their visual beauty, the limited supply of work from famous and deceased “blue-chip” artists such as Pablo Picasso or Mark Rothko means prices will likely continue to climb as demand increases, he added. “Art has become not only an asset class for the super-wealthy, to complement holdings in real estate, stocks, and fixed income, but also a status symbol.”

Technology has also taken art global, contributing to changing tastes by exporting a vision of Western culture, art, and architecture to a range of buyers willing and able to pay, said Diker. “Twenty to 30 years ago, Chinese buyers would be buying Chinese bronzes and ceramics,” he said. “Now they are much more interested in prized Western modern and contemporary art, and that interest is raising the stakes.”

Auction houses are also helping create a buzz in the market by taking works coming up for sale on global tours that let potential buyers see the art in person before they buy. “The houses will move major works around the world in the three to six months before the auction because most people won’t buy a masterpiece with a huge price unless they can preview it,” said Diker. Helping promote the art further are auction house catalogs, which have gone from modest directories with a simple photo and brief provenance for each item to “200-page glossy publications with extensive curatorial notes on many of the higher-priced works,” he said.

Another common practice that helps keep prices high is the use of third-party guarantors who place a guaranteed bid on a piece prior to auction, ensuring the work sells at that price if no one else has offered to buy it for more when the gavel falls. If someone does place a higher bid at auction, the third party will share in the profit. “That has become a big movement in the art market over the past 20 years,” said Diker. “A collector who is comfortable acquiring a work for a specific price will ‘backstop,’ and if the piece goes for over that price, the collector shares in the upside.”

But Diker, whose interest in art was sparked as a child and fueled by the art and architecture courses and studio classes he took at Harvard, said he and his wife collect for “the intellectual challenge and visceral enjoyment of bringing together works that as a collection create a unique dialogue.”

“It’s a lifelong passion,” Diker said, “and it has brought a huge and very important dimension to my life.”

As for the shredded Banksy, its new allure has made it a keeper, at least for now. The winning bidder announced in a Sotheby’s statement that she has decided not to sell. “I was at first shocked,” said the woman, a longtime European collector, “but gradually I began to realize that I would end up with my own piece of art history.”