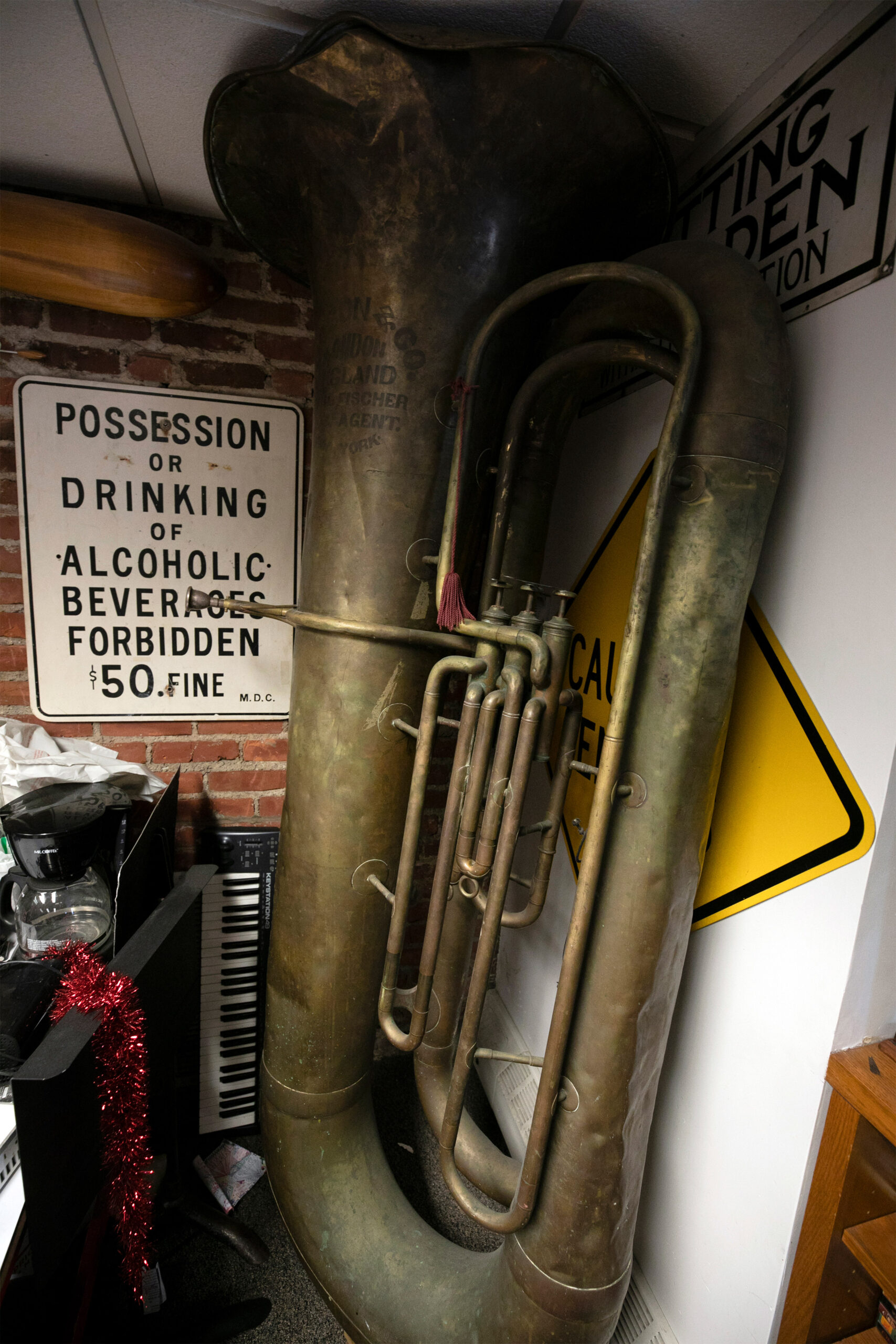

There are tubas, and then there’s this

Harvard University Band Director Mark Olson looks forward to having a fully restored tuba in time for the band’s 100th anniversary concert.

Stephanie Mitchell/Harvard Staff Photographer

The journey into the history of the mammoth Harvard instrument is nearly as epic as it is

In the basement of a house on Mount Auburn Street, behind a microwave and a coffeemaker, is (possibly) the largest tuba in the world. It’s nearly 7 feet tall, has 60 feet of tubing, weighs about 100 pounds, and takes three people to play. Known as a subcontrabass tuba, the instrument has a BBBb pitch, a full octave lower than the lowest traditional tuba.

First-time encounters typically start like this: “Why?”

The gimmick of the instrument’s size was almost definitely a consideration for its creator, says Mark Olson, director of the Harvard University Band — but not the only one. The search for a novel timbre likely also enticed the mind behind the design.

“A tuba is the foundation of a band,” said Olson, noting that an instrument an octave lower than a traditional tuba can add a unique sound to an ensemble.

The second most common question asked about the tuba — “How did this get here?” — is much harder to answer.

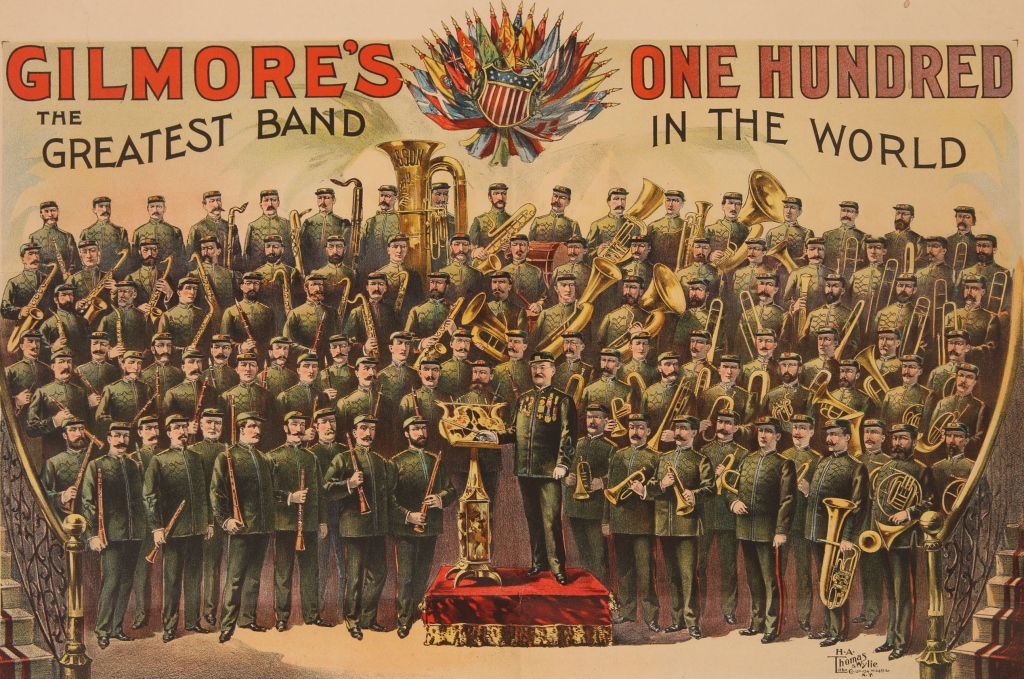

According to a 2014 New York Times article, Harvard’s subcontrabass was originally commissioned by John Philip Sousa. A dedicated group of enthusiasts on the message board TubeNet occasionally review the facts about giant tubas, and they disagree. They believe that Harvard owns the tuba commissioned by American bandmaster Patrick Gilmore for a performance at the 1893 Chicago World’s Fair.

Harvard’s tuba in the Harvard University Band’s basement space; an 1892 lithograph of Gilmore’s One Hundred band.

Photo by Stephanie Mitchell/Harvard Staff Photographer; lithograph courtesy of Soulis Auctions

Stephanie Mitchell/Harvard Staff Photographer

Dave Detwiler, whose blog, “Strictly Oompah,” covers the history of the sousaphone, is in the latter camp. He recently posted an 1892 lithograph of Gilmore’s band, which included a notably large tuba with a layout and design similar to the Harvard instrument.

Two other pictures posted by Detwiler suggest the tuba had landed in Boston by the 1920s. In the first, from 1928, a giant tuba is on the back of a truck, being played in front of the house of Massachusetts Gov. Alvan Fuller. In the second, from a 1929 Boston Globe article, it’s being played by three women, with one standing in the bell of the horn, acting as a stop.

A search for “tuba” in the Harvard archives turns up a 1948 calendar item reporting that “the Harvard Band acquired the famous 6-foot, 10-inch tuba” for $100. Another, more mysterious archival find, a Harvard Bulletin feature from 1972, refers to the instrument as “King Tuba” and mentions a second giant tuba that was cursed, with “disaster [pursuing] each successive owner until one bedeviled bandleader rowed out into Lake Michigan and scuttled the thing.”

In an effort to keep its giant piece of history from fading into obscurity, the Harvard University Band will have King Tuba restored in March, in time for the group’s 100th anniversary concert in October. Steve Dillon, whose company Dillon Music will perform the restorations, expects a “very difficult” process, and will close his shop for a week so that six workers can focus exclusively on the tuba.

Once the instrument is restored and returned to the band’s Mount Auburn Street headquarters, Olson expects it will sit nicely alongside another Harvard treasure: a baton certified by Guinness World Records as the largest on earth.