Fentanyl deaths alone spiked 45 percent in 2017, according to the CDC.

AP photo

A nation nearer to the grave

Another decline in U.S. life expectancy signals urgent need for more comprehensive strategy against opioids, suicide, specialist says

Life expectancy in the U.S. declined in 2017, largely because of increases in suicide and lethal overdose, according to reports from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

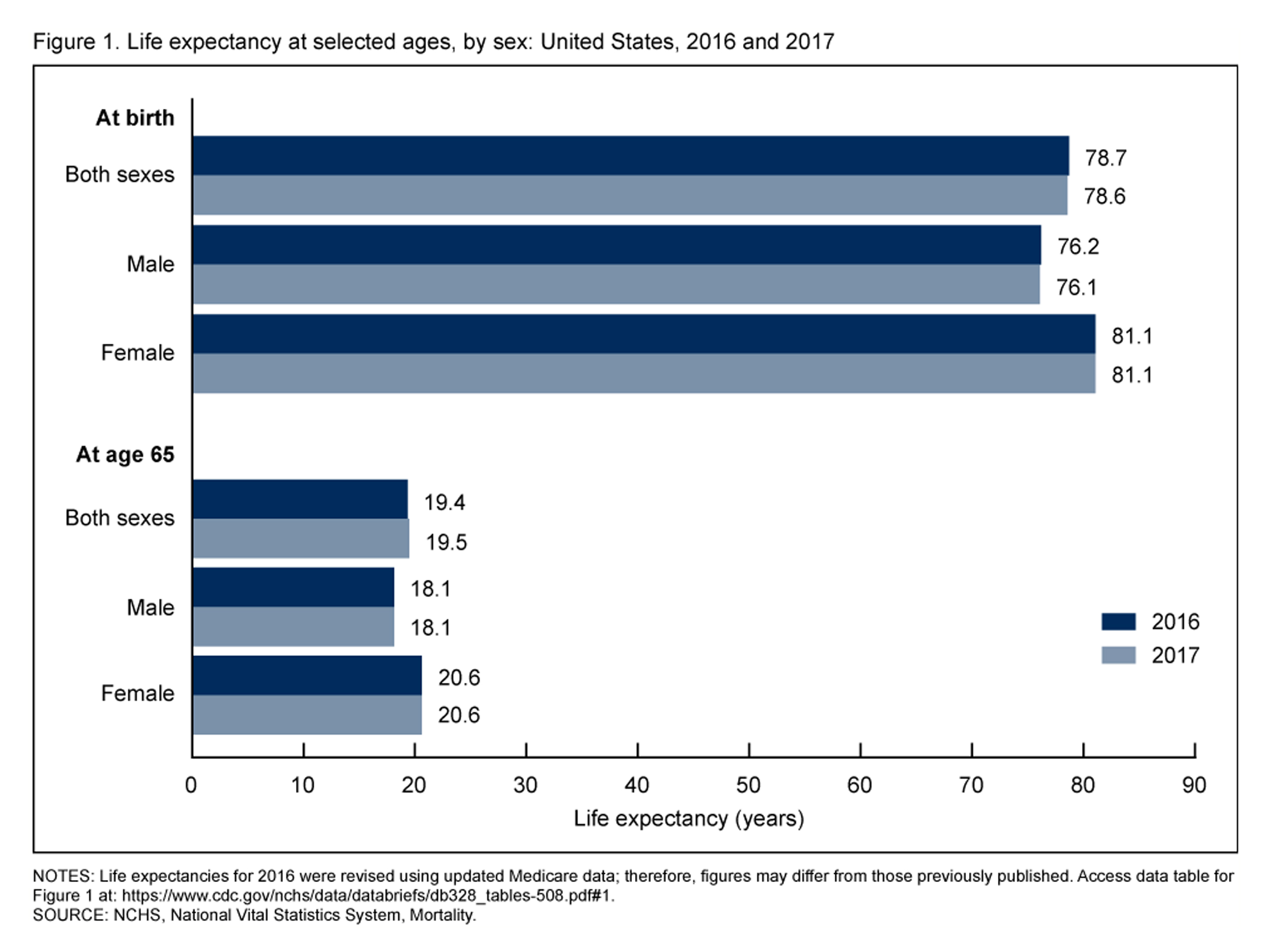

Though slight, the drop from 78.7 in 2016 to 78.6 in 2017 marks the third consecutive year of decline in a statistic that in 1900 stood at 49.24.

Experts see the fingerprint of the opioid epidemic in the numbers, as well as the economic inequality, depression, and despair that elevate suicide risk. R. Kathryn McHugh, an associate psychologist at McLean Hospital and an assistant professor of psychology at Harvard Medical School, responded to the CDC data in an interview with the Gazette.

Q&A

R. Kathryn McHugh

GAZETTE: One report showed that life expectancy fell between 2016 and 2017 and two others detailed the key factors in that decline: suicide and overdose deaths. Did those trends surprise you?

McHUGH: Unfortunately, no. Both the suicide trend and drug overdose trend have been going on for many years now. Drug overdose in particular has been on an exponential growth curve since the late 1970s/early 1980s, with tremendous escalation since around 2013.

GAZETTE: The overdose statistics — up 9.6 percent — indicate a huge one-year increase. Does that reflect what you’re seeing in your clinical practice?

McHUGH: Yes and no. The folks I see are all generally receiving frontline care, consisting of medications as well as behavioral therapies. However, we know that when someone leaves treatment their risk for relapse and overdose is very high.

The good news in this story is we actually have effective treatments that can both decrease opioid use and decrease overdose deaths. We actually know how to treat this disorder. It’s an issue of getting more people into treatment and retaining people in treatment.

GAZETTE: How do we do that better? I’ve heard other experts say the same thing about medication-assisted treatment: We know how to deal with this. But the number of overdose deaths is still going up. What are the main hurdles and how do we get over those?

McHUGH: This is not a one-problem issue. We can’t just pull one lever and solve this crisis. It’s not just about opioid prescribing. It’s not just about pain. It’s not just about economic disparity. Really, there are a number of factors that come into play. This includes everything from access to health insurance and access to effective treatment, to physician prescribing practices and regulations on pain treatment, to issues of stigma, to the potency of the opioid supply.

Access to mental health care is another major issue. Psychiatric illnesses, exposure to trauma, and certainly suicidality are all part of the overdose crisis. We know psychiatric disorders are a risk for opioid medication misuse and for opioid-use disorder, as well as for suicide. However, access to effective mental health care remains extremely limited. So there are many levers that we need to pull.

CDC.gov

GAZETTE: Do you see the overdose epidemic continuing?

McHUGH: It’s hard to say. Unfortunately, last year’s increase of 9.6 percent suggests that the efforts that are now ongoing — and there’s quite a bit of attention on this — are not sufficient. A big part is access to fentanyl and fentanyl analogs, which are extremely potent opioids. That’s really driving this continued increase in deaths.

There are some pockets of good news. For example, the overdose rate has been dropping in some places, like in Massachusetts.

GAZETTE: Nationwide, fentanyl deaths were up 45 percent from 2016 to 2017. That made me wonder if fentanyl alone might be responsible for most of the increase.

McHUGH: There are a couple of pieces to that. Heroin-related deaths have plateaued in the last few years. What the CDC report refers to as “natural and semisynthetic opioids” — which are mostly prescription opioids — are also starting to flatten out. The prescription opioids’ plateau is likely due to efforts to improve the safety of opioid prescribing. The overprescription of opioids was one of the driving factors in starting this crisis.

Really, the only thing increasing exponentially is fentanyl, and, since around 2013, that has really taken off. In the Boston area, the people I work with clinically will say to me that you can’t even get heroin anymore, everything on the street is fentanyl.

GAZETTE: Does that require a shift in approach?

McHUGH: There are a couple of open questions about that. For overdose, Narcan does work with fentanyl, though you typically require higher doses and multiple administrations. In terms of the acute rescue, that ends up being an issue.

Certainly you can have more medical consequences because it’s a more severe overdose. The treatment of the disorder is the same — medication-assisted treatment, although there is more research needed on whether people who are using fentanyl have additional or different treatment needs. A big issue is if you have such potent opioids available and that’s what is accessible to people, the risk of unintentional overdose is heightened. We really worry about someone in treatment, doing well, who drops out. At that point, their tolerance for opioids has dropped and they are at very high risk of overdosing if they relapse.

GAZETTE: If they get an extra-potent drug like fentanyl …

McHUGH: Exactly. And fentanyl doesn’t just show up in the heroin supply. People can buy from an illicit source something that looks like a standard prescription opioid — for example, it might look like a 30 mg Percocet — but it was produced illicitly and it has fentanyl in it. So, someone might think they know exactly what opioid dose they are getting, but they’re getting a much higher dose and are at a much higher risk of overdose. Fentanyl has also been showing up in illicitly produced benzodiazepines, which is another dangerous combination.

“We can’t just pull one lever and solve this crisis. It’s not just about opioid prescribing. It’s not just about pain. It’s not just about economic disparity.”

GAZETTE: How similar are this problem and suicide? I wonder if the underlying factors are related.

McHUGH: We’ve drawn a false dichotomy between unintentional overdose and suicide. There’s evidence to suggest that you don’t fall in one category or another, that there are actually quite a few shades of gray between the two. For example, in what we might categorize as an unintentional overdose, there might be significant desire to die, or even ambivalence: “I don’t care if I live or die,” or “I know I might die but I just want some relief.”

There’s actually more overlap between these two behaviors than we typically acknowledge. Both suicide and overdose are exceptionally common in people with opioid-use disorder. Both contribute to the high mortality rates we see in this population.

The other piece is that many of the risk factors for overdose and suicide overlap. Risk factors at the individual level — exposure to trauma, chronic pain, psychiatric illness, financial or other kinds of stress — and even at the societal level — access to insurance, economic distress, access to opportunity, etc. — are common risks for both behaviors. There’s probably more overlap than we’re aware of at this point.

GAZETTE: Early on, you talked about what a complicated problem this is. But the increase in these numbers since 1999 is really just astonishing. The average reader might ask a simple question: What’s going on in this country?

McHUGH: There’s a tendency to try to look for the smoking gun here. Is it the economy? Is it the [political] discourse? Is it hopelessness? There really are a number of different things that can be contributing.

Certainly, there’s data to suggest that economic depression is associated with both overdose and suicide. Some of the regions that have been hardest hit are regions in which opportunities have been limited, where there’s certainly economic stress. But opioid misuse is an issue that cuts across our entire society. There is no subgroup — men, women, any age, any socioeconomic group — that is immune from this problem.

You hear the term “deaths of despair” used to describe the epidemic of overdose and suicide. That certainly is a component of it, but there are also many other components that are really important to keep in mind. This is unquestionably a complex problem. We know that certain factors — exposure to trauma, untreated psychiatric illness, untreated pain — all play a role in risk for opioid misuse. And certainly access to prescriptions plays a role. The increase in opioid prescriptions over the last 20 to 30 years has been tremendous. Likewise with benzodiazepine prescriptions. These have been strongly correlated to the increases we see in overdose deaths.

GAZETTE: Your research involves finding or evaluating treatments. What are you learning from your work?

McHUGH: There are a lot of really interesting things going on now, in terms of trying to address this in the research community. Part of what my work is focused on is, how do we address not just the substance-use disorder but all of the other things that come with it? For example, we are trying to answer questions about the role of stress in opioid misuse and how do we best treat the conditions that commonly co-occur with opioid-use disorder, such as pain and psychiatric illnesses.

We have a couple of studies ongoing now that examine how to best treat anxiety and stress in people with opioid-use disorder. If we address their opioid-use disorder but don’t help lift the depression or anxiety or post-traumatic stress disorder that comes along with it, even if people do successfully stop using opioids, they are still suffering quite a bit and are at a higher risk for relapse.

What we’re still learning is how to treat the whole person, treat all elements that come with this. In many cases it is also suicidal thoughts, it is also anxiety, it is also depression.

GAZETTE: And does that involve constructing a care team with different characteristics?

McHUGH: Medication-assisted treatment is really the standard of care. It makes a tremendous difference in terms of getting people off opioids and keeping them from overdosing. Much of what we’re looking at now is how to improve the treatment-response rate.

Right now, the response to treatment is about 50 to 60 percent. Critically, that is many times better than no treatment, or medical detoxification alone. There is really no comparison in terms of outcomes. But we need to be doing better than that.

A lot of ongoing research is focusing on is how to build up the care team around people with behavioral treatments, such as cognitive behavioral therapy — which my work focuses on — as well as things like better case management, working with people to address things like social determinants of health, making sure that they have adequate health insurance and housing. There’s also increasing attention to the potential of peer-based services, whether that’s the self-help community or recovery coaches as part of the treatment team.

The data are still coming in. There really is a tremendous need for research in this area to continue to improve treatment, to improve models of care — like how to best link people from the hospital into medication-assisted treatment, and, critically, to begin to better understand effective prevention of opioid misuse so that we are catching people long before a bad outcome.

Interview was edited for clarity and length.