Courtesy of Harvard Art Museums

Probing the secrets of Sardis

Researchers explain findings, import at long-running archaeological dig in Turkey

One of the most prestigious and longest university archaeological excavations in the world, Sardis stands alone.

The two-millennia-old site in western Turkey is more than its Lydian pottery or striking acropolis. As a series of presentations and discussions at the Harvard Art Museums made clear, it is also a community, where faculty and students, interns and archivists share the important work, much of which is done after the shovels and sieves have been put away.

The talk on Friday, part of Worldwide Week at Harvard 2018, began with presentations by several faculty and museum staff members involved in the exploration. Susanne Ebbinghaus, the George M.A. Hanfmann Curator of Ancient Art and head of the division of Asian and Mediterranean Art at the Harvard Art Museums, opened the event, describing the site and the scope of the venture, which is now in its 60th year.

Adrian Stähli, professor of classical archaeology in the Department of the Classics and head of the faculty oversight committee on the expedition, said, “Sardis is among all excavations one of the most prestigious and one of the oldest.”

The first large-scale scientific exploration of the site actually began in 1910, Stähli and colleagues said. Under the direction of Professor Howard Crosby Butler of Princeton, this was a huge venture, with a staff of 300 and heavy earth-moving equipment that would no longer be considered suitable for such delicate work. But the initial excavation was interrupted by World War I, and Butler died in 1922. When George M.A. Hanfmann, professor of archaeology at Harvard, arrived in 1958, it was with a smaller crew but using the more cautious techniques that prefigure the work today.

Labeling the site “one of the few we would call a ‘big dig,’” Stähli said it is also one of a few that can offer both undergraduates and graduate students substantial experience in the field.

Students and the public can stay on top of current findings and ongoing work through the website of the standing committee on archaeology, said Rowan Flad, the John E. Hudson Professor of Archaeology. The site also contains a newsletter.

Nicholas Cahill, field director of the Sardis expedition, lectures at the site in western Turkey.

Courtesy of Harvard Art Museums

With the aid of slides, Nicholas Cahill, field director of the Sardis expedition, showed the group the site, which has stood at the crossroads of Europe and Asia from its time as the capital of an empire through its role as a regional center for the Persians, Greeks, Romans, and Turks.

Cahill, the Simona and Jerome Chazen Distinguished Chair in Art History at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, discussed how new discoveries continue to expand knowledge of Sardis and its role. Officials on previous excavations, for example, have read works by classical writers like Herodotus for clues to where the center of ancient Sardis lay. However, the hard work of excavation — such as looking at the fill used to build terraces for the dramatic acropolis — have led to new directions and revealed even older material than previously known.

“Sardis combines a little bit of everything, or rather a lot of everything,” said Cahill. “From monumental Roman arches, temples, and sculptures to religious transformations, from paganism to monotheism, Greek, and Latin inscriptions,” he said.

While technology has aided the work, including aerial photography by drone, much still must be done by hand. Bahadır Yıldırım, expedition administrator for Sardis at the Harvard Art Museums, and Frances Gallart Marqués, the Frederick Randolph Grace Curatorial Fellow in Ancient Art at the Harvard Art Museums, discussed the painstaking labor of cataloging and archiving finds, much of which is done at the museum’s research facility in Somerville.

“The work is not always glamorous or exciting,” said Cahill. “But it is always important.”

It can also, say student interns from the site, be rewarding.

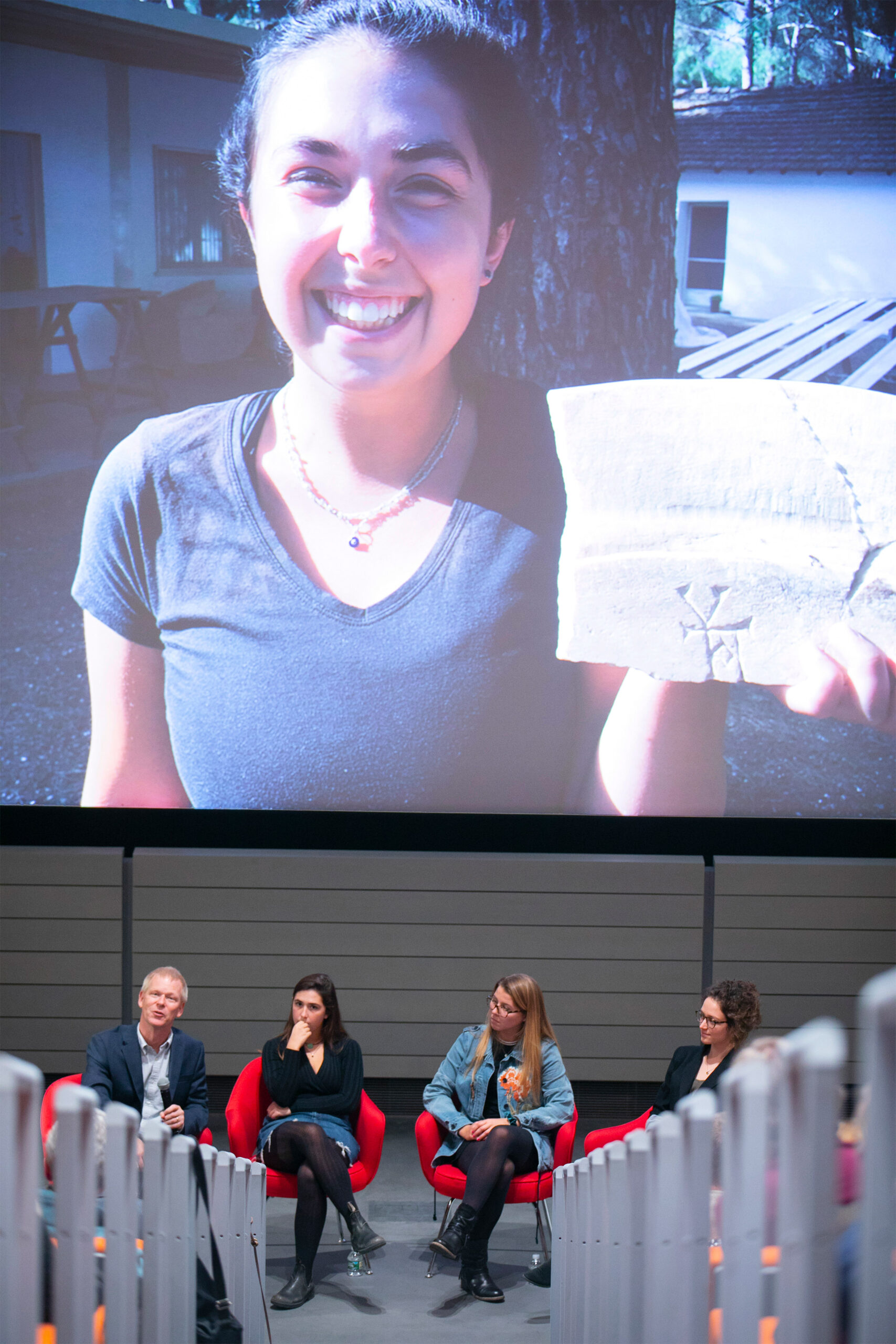

Sophomore Emma Humphrey, projected in a slide, displays what’s likely a stonemason’s monogram, “a little secret” she found while piecing together fragments. Sitting below (from left) are Cahill, Humphrey, Maria Boyle, and Julia Judge.

Stephanie Mitchell/Harvard Staff Photographer

Boyle conserves mosaic with the Turkish team.

Courtesy of Harvard Art Museums

“I have excavated at Sardis for two seasons now,” said Julia Judge, a fourth-year Ph.D. student in classical archaeology. “I think we all feel really lucky to work at Sardis because it’s very rare that you have a site that is so rich and so interesting at every phase. I had this incredible opportunity to work with a part of the site that’s truly historically significant.”

Calling herself “basically an extra set of hands,” Maria Boyle, a third-year undergraduate studying anthropology and archaeology, described her experience as “a super fun summer.”

“It’s incredible to work in the place and walk among the ruins of the Temple of Artemis,” she said.

Emma Humphrey, a sophomore studying computer science, actually made a discovery. She was helping one of the supervising conservators brush clean and re-assemble fragments, when she noticed a monogram at the back of one of the pieces. She assumed it had already been cataloged, but pointed it out anyway.

“I found out that it was actually news, which was exciting until we realized that nobody knew what it meant,” she said with a laugh. After some discussion, she recalled, the crew decided it was probably a stonemason’s mark, “like a receipt or a personal advertisement,” she said.

“I like this monogram because it feels like a little secret that I found.”