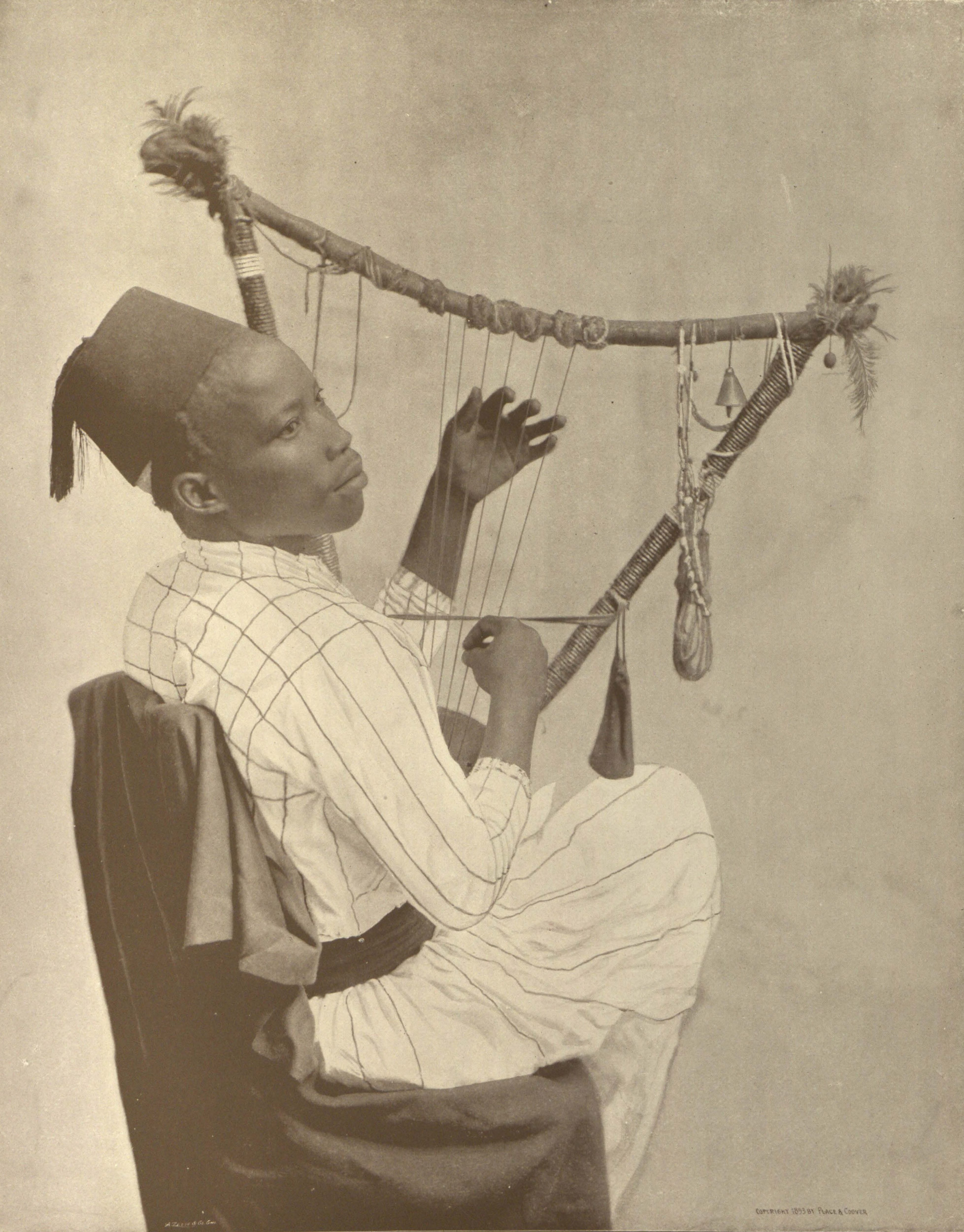

Wikimedia Commons

Putting a new face, and new faces, on the 1893 World’s Fair

Rare portraits of Midway performers spark new research

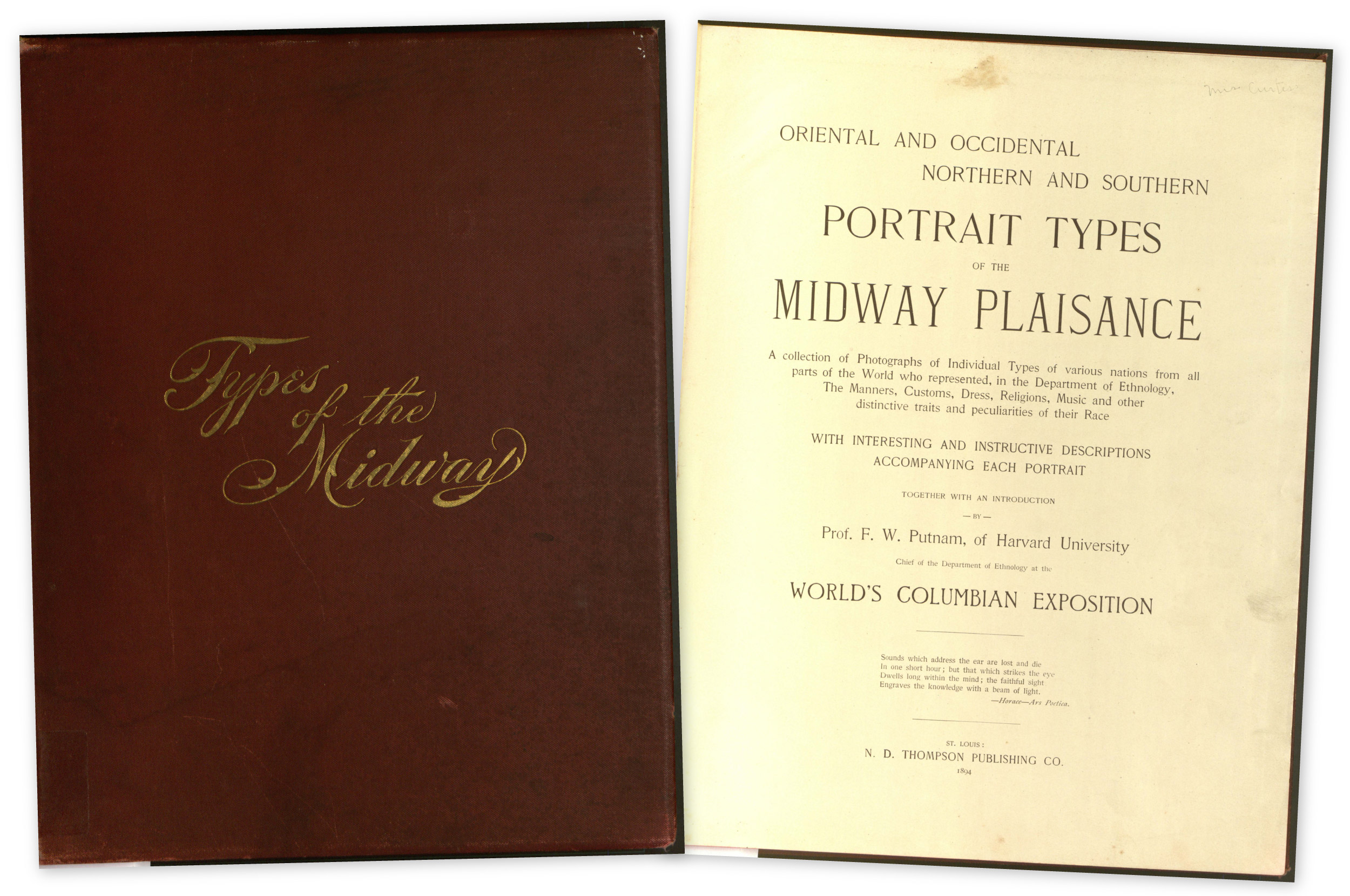

The ethnic villages of the Chicago World’s Fair of 1893 exposed Americans to different cultures, but they also promoted stereotypes — many of which are reflected in a picture book from the era displayed in Harvard’s Peabody Museum.

To counter the book’s often-condescending descriptions of the people who were recruited from around the world to work in the fair’s Midway — in attractions such as the Moorish Palace and Eskimo Village — curators enlisted students to do research. The result is a digital display pairing the book’s 80 full-page portraits of Midway performers with new bios and context provided by students.

“The descriptions in the book tend to objectify the people of the Midway, rather than recognizing them as individuals. That’s why it’s interesting to research them now,” said Nam Kim, a sophomore who searched newspapers and ads for details about two Samoans identified in the book as William and Mele.

Ilisa Barbash, the museum’s curator of visual anthropology, asked students to explore how Midway personalities were presented and perceived in addition to basic biographical questions: Where were they from? Who brought them to Chicago? What happened to them after the fair?

“The descriptions in the book tend to objectify the people of the Midway, rather than recognizing them as individuals. That’s why it’s interesting to research them now.”

Nam Kim, student researcher, pictured below

Photos by Stephanie Mitchell/Harvard Staff Photographer

Curators Diana Loren (left) and Lisa Barbash.

Katie Wu ’17 said she was surprised to read that a duo called the Farbianu sisters from Romania were musicians in the Moorish Palace.

“I thought, wait a second, they’re from Romania, but they’re performing in the Moorish Palace? You bring in these ‘exotic’ cultures that most visitors wouldn’t have experienced, and you have to unpack that,” Wu said. “Eastern European culture was conflated with Arab culture.”

After the fair’s six-month run saw nearly one-quarter of Americans visit, promoters sought to sustain interest with “Portrait Types of the Midway Plaisance,” originally published in 10 volumes in 1894, advertised in newspapers for 10 cents each.

Barbash said curators included the book to contrast the commercialized Midway attractions with the anthropology exhibits in the main court, which were supervised by the Peabody’s director at the time, Frederic W. Putnam.

More like this

“Many Peabody visitors — and curators — can identify a fictive ancestor in ‘Portrait Types,’” Barbash said. “That’s why it’s so important to research the deeper history behind the portrait subjects. … We hope that the aspects of their exploitation, exoticization, and racist treatment in the past calls attention to such problems in the present.”

In the fall, Kim will focus her research on two German performers, Mary Moser and Gustav Herold. Barbash and Diana Loren, the museum’s director of academic partnerships, said they will continue to enhance the exhibit with student work.

“All the World Is Here: Harvard’s Peabody Museum and the Invention of American Anthropology” can be viewed 9 a.m.–5 p.m. daily at the Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology, 11 Divinity Ave., Cambridge.

Portraits courtesy of the Peabody Museum

“Unnecessarily and unusually noisy,” Dama Waja reportedly answered when asked how she viewed Americans. Many workers in the Javanese Village, popular for its tea house and 1,000-seat theater, came to Chicago from a Dutch coffee and tea plantation in Java, student research found.

* * *

Student researcher Kim encountered numerous news stories sexualizing Samoans, including 13-year-old Mele Leli. Despite her age, she was characterized as a Midway heartbreaker and noted in one report for her “beautiful expressive eyes.” Kim wonders if another Samoan, William, was named after a Christian missionary, and she thinks she tracked down another photo of him.

* * *

Mary Dookshoode Annanuk, a Labrador Inuk, resided in the Eskimo Village. Despite the Chicago heat, organizers demanded her group wear traditional sealskins while demonstrating kayaking, dog sledding, hunting, and fishing techniques. After two Inuit wore jeans instead, managers locked the families in their huts until they agreed to obey the dress code. The Inuits later successfully sued for unfair labor conditions.

* * *

Sophie and Rosa Farbianu performed in the Midway’s Moorish Palace — a labyrinthine castle with a hall of mirrors, harem, and collection of wax figures. The sisters were part of the First Roumanian Royal Concert Band, whose performances were reviewed glowingly in accounts unearthed by Wu.

* * *

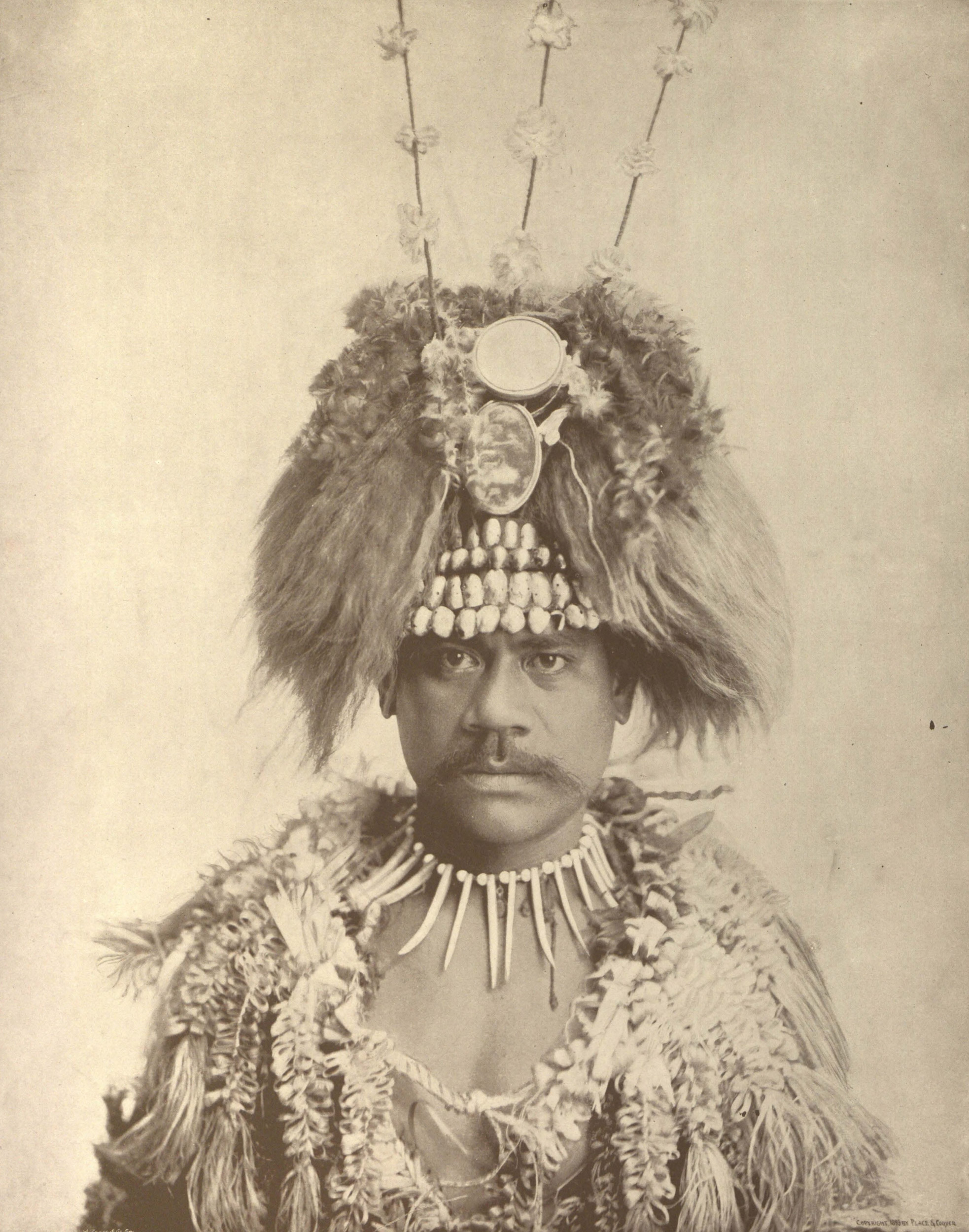

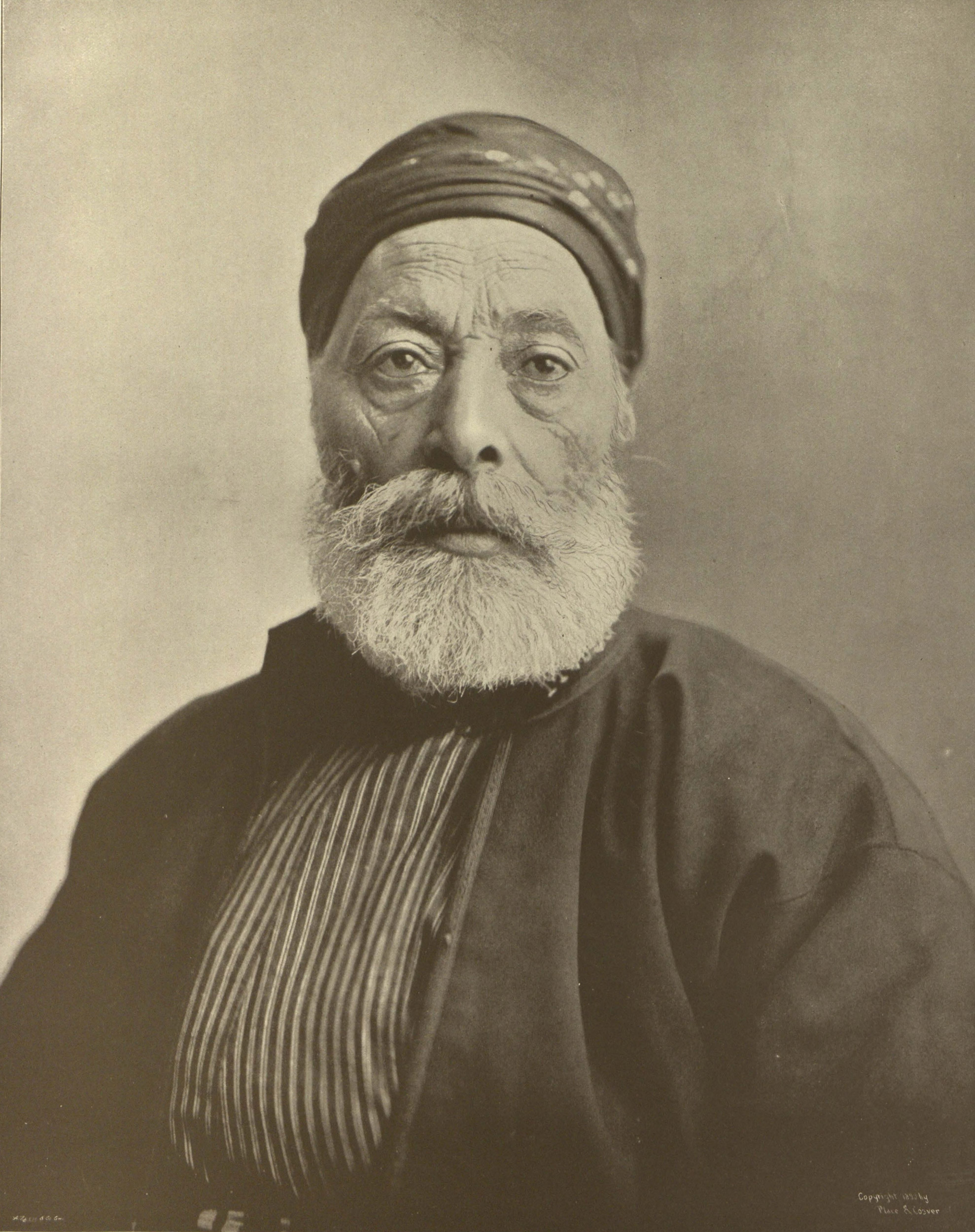

“Far-Away-Moses,” who gained fame as Mark Twain’s tour guide and dragoman in “The Innocents Abroad,” worked in a bazaar in the Turkish Village, joined there by Jamelee of Syria, who likely was a belly dancer in a cafe. Abal Kader of Southern Sudan probably played his traditional lyre-like kissar in the neighboring Street in Cairo, Barbash said.

* * *

Ki Hing and Foke Sing were among the more than 200 entertainers who lived and performed in the Chinese Theater. Despite China’s industrial achievements, the country had no exhibition building outside the Midway, reflecting anti-Chinese sentiment at the time.

* * *

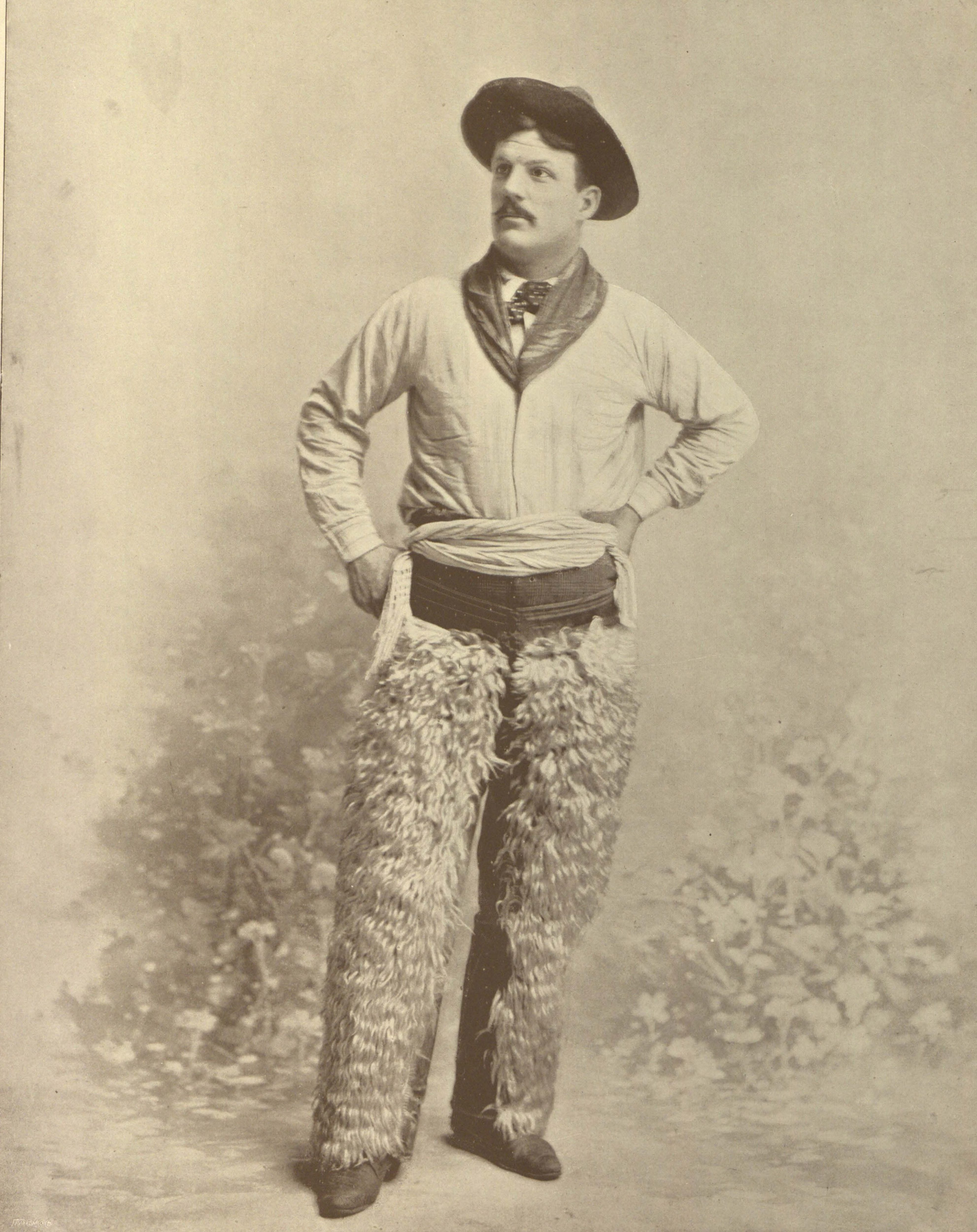

A skilled horseman, the Laramie Kid (Harry Shanton) performed in Buffalo Bill’s Wild West traveling show. He was joined in the show by Rain-in-the-Face, a warrior mythologized in a Longfellow poem about the Battle of Little Big Horn.

* * *

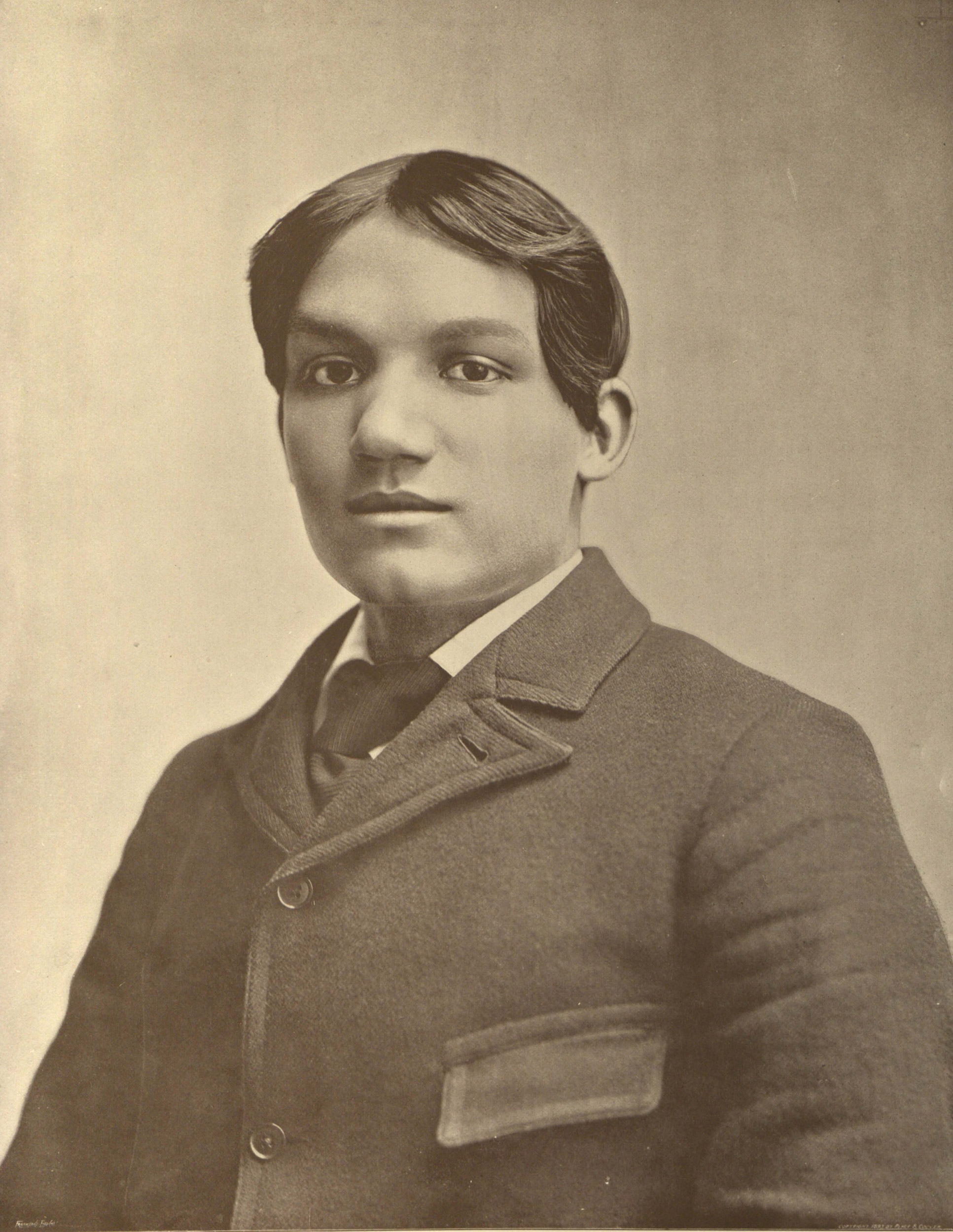

“Antonio Apache” recruited and supervised Navajo performers but wasn’t a performer himself. Western-educated and employed as an assistant by Frederic W. Putnam, head of anthropology at the fair, Antonio was held up in the “Portrait Types” caption as model of cultural assimilation, but his identity as a Native American was later contested.

* * *

In the fall, Kim will research Gustav Herold and Mary Moser, who worked in the German Village.