Jacob Scherba always assumed he would be an actor, but a brush with death and his sister’s affliction with a rare disorder led him to merge engineering and medicine.

Kris Snibbe/Harvard Staff Photographer

Discovering a ‘richness’ in Harvard’s diversity

Jacob Scherba ’18 credits peers and professors with opening up his world

This is one in a series of profiles showcasing some of Harvard’s stellar graduates.

Only 750 miles separate Cambridge, Mass., from Jacob Scherba’s hometown in the heartland, but there were times when it felt like a million miles. Hartland, Mich., is “a pretty rural, conservative” township where people’s attitudes feel similar and politics aren’t talked about much, because “everyone just assumes” you share their views, Scherba said.

As the first in his high school to be accepted by Harvard, Scherba’s decision to come here to study biomedical engineering raised eyebrows among his classmates and even some advisers, he says, since the University of Michigan is the traditional destination for the area’s best students. “One person from my church, the last thing he said to me was, “Get in, get your degree, and get out before those liberals change you.’”

Scherba, who will get that degree this week, admits he arrived in Cambridge with a distorted idea of what life at Harvard would be like.

“I think I had a very caricatured perspective on it because I’d never known anyone who’d gone there. I thought it would be a very academic, formal institution and … I would do all my learning from the professors. And what I found is, while there are some absolutely incredible professors here, most of the learning that I’ve done has been from my peers,” he said.

“There’s an incredible diversity of talents and perspectives and backgrounds that creates a richness that I was able to learn from. I grew up in a very homogeneous community, so that was very different and overwhelming at first,” he said. “I think that’s probably one of the most humbling things that I got here, was how incredible my classmates are.”

But it all almost didn’t happen.

Just weeks into his first semester, Scherba was walking back from crew practice when he went into cardiac arrest. He spent the next year in and out of Massachusetts General Hospital as doctors worked to diagnose the problem. But he was determined not to let it define or derail his freshman year.

“I had this incredible opportunity in front of me, I didn’t want to give it up. I was excited to be here. So, I would be hooked up to the hospital’s Wi-Fi trying to get work done and I was adamant that I would not take an extension on anything because I didn’t want that to be used as a reason to say, ‘You’re behind on work, you need to take a leave of absence,’” he said.

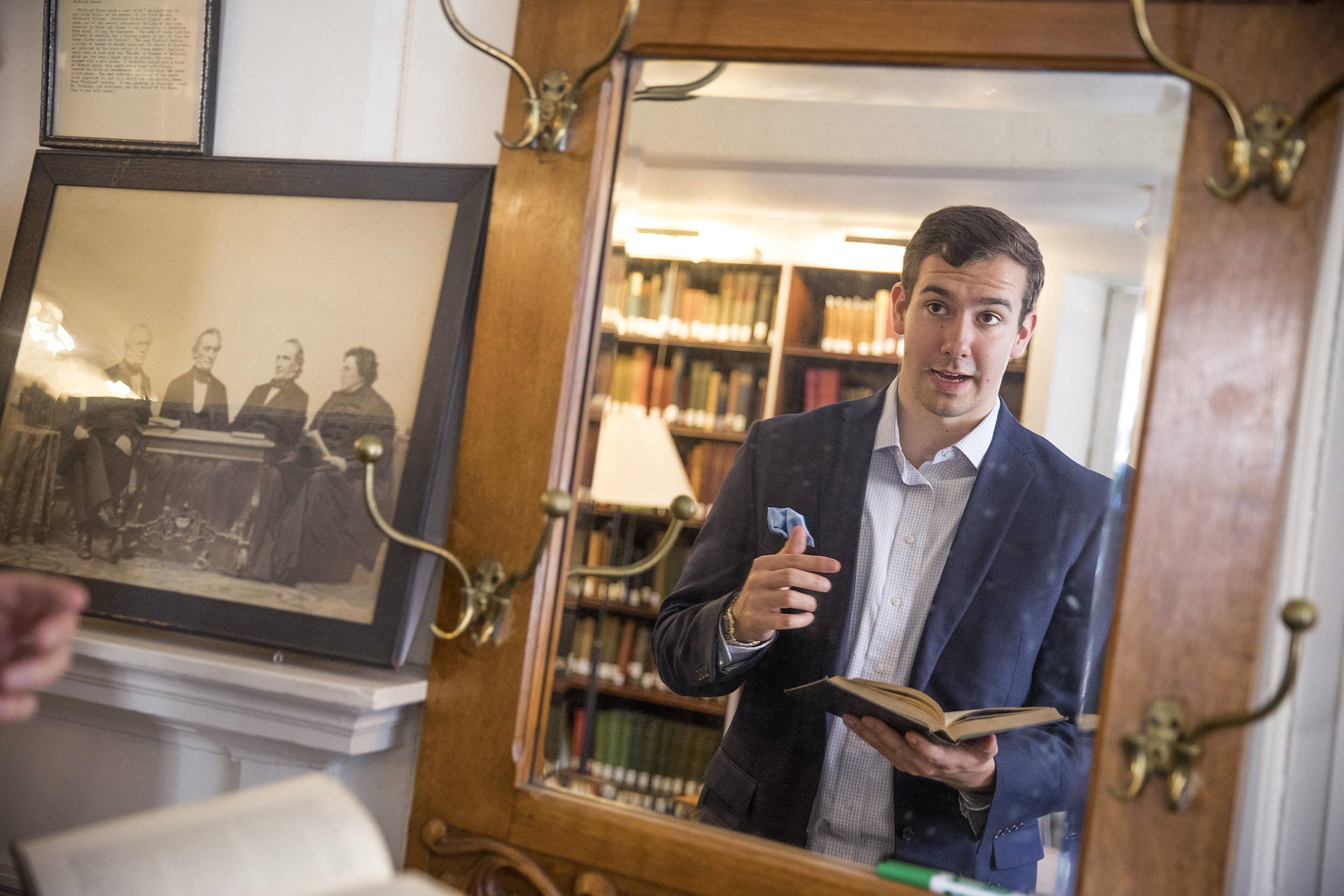

Scherba rehearses lines in the Junior Commons Room for a Kirkland Drama Society production, for which he serves as president. On the left is a photo of five historical Harvard presidents including John Adams.

Kris Snibbe/Harvard Staff Photographer

Now fully recovered, Scherba said his time as a patient helped him realize that he wanted to study medicine.

What also motivated him was his sister’s childhood struggles with Ehlers-Danlos syndrome, a connective tissue disorder that makes the joints painfully hypermobile. His thesis focused on designing a less expensive, more efficient platform for testing and manipulating genetic markers of orthopedic tissue used to study the relatively uncommon disorder and other diseases of bone and tendon. He conducted research during the academic year and continued in the John A. Paulson School of Engineering and Applied Sciences (SEAS) as a summer fellow in its Program for Research in Science and Engineering (PRISE).

Working at SEAS professor David Mooney’s lab, part of the Wyss Institute, Scherba used his bioengineering skills as a rat dentist. On a project to develop new material for dental fillings, it fell to Scherba, the least experienced team member, to test the different materials by giving lab rats fillings in their tiny molars — about half the size of a grain of rice.

Beyond the lab, Scherba served as a teaching fellow helping students get through applied math and other difficult subjects and, when he can, he indulged his longtime passions for acting and singing. In high school, he had small roles in a few films, and with his deep baritone, he did voiceover work. “For a while, I thought I was going to be a film actor and be successful enough in acting that I could self-fund some of my research and be free from the politics of government funding,” sort of like Iron Man, he joked.

A resident of Kirkland House, Scherba was president of the Kirkland Drama Society. He also regularly performed the national anthem at Harvard athletic events and has sung at the finals of the Beanpot, Boston’s annual crosstown college hockey tournament.

Scherba will attend Duke University in the fall to study bioengineering in a dual M.D.-Ph.D. program. He’s drawn to pediatric surgery but hopes ultimately to teach at a university where he can conduct research and see patients.

What he’ll treasure most from his time in here, thanks in part to Harvard’s residential House system, is getting to know students from different walks of life, with different perspectives, who study different subjects, like religion or classics.

It’s been a “powerful experience learning from people’s stories and experiences that are so radically different from mine and realizing the privileged position that I am in because of my demographics,” said Scherba.

On Commencement Day, “I’ll be thinking about how much I’ve learned from my peers and how fortunate I am to have had this experience.”