With mindfulness, life’s in the moment

Illustration by Kathleen M.G. Howlett

Those who learn its techniques often say they feel less stress, think clearer

Second of two parts

On a cold winter evening, six women and two men sat in silence in an office near Harvard Square, practicing mindfulness meditation.

Sitting upright, eyes closed, palms resting on their laps, feet flat on the floor, they listened as course instructor Suzanne Westbrook guided them to focus on the present by paying attention to their bodily sensations, thoughts, emotions, and especially their breath.

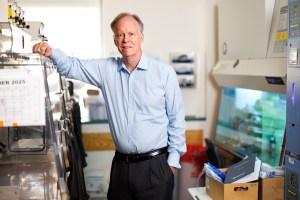

Suzanne Westbrook, a retired internal-medicine doctor, taught an eight-week program that focused on reducing stress.

Rose Lincoln/Harvard Staff Photographer

“Our mind wanders all the time, either reviewing the past or planning for the future,” said Westbrook, who before retiring last June was an internal-medicine doctor caring for Harvard students. “Mindfulness teaches you the skill of paying attention to the present by noticing when your mind wanders off. Come back to your breath. It’s a place where we can rest and settle our minds.”

The class she taught was part of an eight-week program aimed at reducing stress.

Studies say that eight in 10 Americans experience stress in their daily lives and have a hard time relaxing their bodies and calming their minds, which puts them at high risk of heart disease, stroke, and other illnesses. Of the myriad offerings aimed at fighting stress, from exercise to yoga to meditation, mindfulness meditation has become the hottest commodity in the wellness universe.

Modeled after the Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction program created in 1979 by Jon Kabat-Zinn to help counter stress, chronic pain, and other ailments, mindfulness courses these days can be found in venues ranging from schools to prisons to sports teams. Even the U.S. Army recently adopted it to “improve military resilience.”

Harvard offers several mindfulness and meditation classes, including a spring break retreat held in March for students through the Center for Wellness and Health Promotion. The Office of Work/Life offers programs to managers and staff, as well as weekly drop-in meditation sessions on campus, online guided meditation resources, and even a meditation phone line, 4-CALM (at 617.384.2256).

“We were tasked to find ways for the community to cope with stress. And at the same time, so much research was coming out on the benefits of mindfulness and meditation,” said Jeanne Mahon, director of the wellness center. “We keep offering mindfulness and meditation because of the feedback. People appreciate to have the chance for self-reflection and learn about new ways to be in relationships with themselves.”

More than 750 students have participated in mindfulness and meditation programs since 2012, said Mahon.

Part of mindfulness’ appeal lies in the fact that it’s secular. Buddhist monks have used mindfulness exercises as forms of meditation for more than 2,600 years, seeing them as one of the paths to enlightenment. But in the Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction program, mindfulness is stripped of religious undertones.

Mark Dennis (from left), Kelly Romirowsky, and Ayesha Hood practice meditation. Metta McGarvey (not pictured) teaches the practice of mindfulness, a workshop for educators inside the Gutman Conference Center.

Kris Snibbe/Harvard Staff Photographer.

Mindfulness’ popularity has been bolstered by a growing body of research showing that it reduces stress and anxiety, improves attention and memory, and promotes self-regulation and empathy. A few years ago, a study by Sara Lazar, a neuroscientist and assistant professor of psychology at Harvard Medical School (HMS) and assistant researcher in psychiatry at Massachusetts General Hospital, was the first to document that mindfulness meditation can change the brain’s gray matter and brain regions linked with memory, the sense of self, and regulation of emotions. New research by Benjamin Shapero and Gaëlle Desbordes is exploring how mindfulness can help depression.

The pioneer of scientific research on meditation, Herbert Benson, extolled its benefits on the human body — reduced blood pressure, heart rate, and brain activity — as early as 1975. He helped demystify meditation by calling it the “relaxation response.” Benson is director emeritus of the Benson-Henry Institute for Mind Body Medicine at Massachusetts General Hospital and Mind/Body Medicine Distinguished Professor of Medicine at HMS.

In the 1980s, mindfulness had yet to become a buzzword, recalls Paul Fulton, a clinical psychologist who has practiced Zen and insight meditation (vipassana) for more than 40 years. In the mid-1980s, when he was working on his doctoral dissertation on the nature of “self” among Buddhist monks, speaking of mindfulness in a medical context among scientists was “disreputable,” he recalled.

“Gradually because of the research, it became chic, no longer disreputable,” said Fulton, a lecturer in psychology in the Department of Psychiatry at HMS and co-founder of the Institute for Meditation and Psychotherapy. “And now you can’t step a foot out of the house without being barraged by mindfulness.”

Melanie Denham, head coach of Harvard women’s rugby team, recently attended a mindfulness workshop, intrigued by the idea of incorporating the techniques into her players’ training regimen to help them cope with the pressures of “expectation and performance.”

Mindfulness meditation made easy

- Settle in: Find a quiet space. Using a cushion or chair, sit up straight but not stiff; allow your head and shoulders to rest comfortably; place your hands on the tops of your legs with upper arms at your side.

- Now breathe: Close your eyes, take a deep breath, and relax. Feel the fall and rise of your chest and the expansion and contraction of your belly. With each breath notice the coolness as it enters and the warmth as it exits. Don’t control the breath but follow its natural flow.

- Stay focused: Thoughts will try to pull your attention away from the breath. Notice them, but don’t pass judgment. Gently return your focus to your breath. Some people count their breaths as a way to stay focused.

- Take 10: A daily practice will provide the most benefits. It can be 10 minutes per day, however, 20 minutes twice a day is often recommended for maximum benefit.

“In and out of the classroom, these student-athletes are immersed in a highly competitive culture,” said Denham. “This is stressful. This kind of training can develop a more-skillful mind and a sense of focus and well-being that can help them better maintain control and awareness of their thoughts, emotions, and presence in the moment.”

The growing interest in the field is reflected in Harvard’s course catalog. This spring, Lazar is teaching “Cognitive Neuroscience of Meditation,” Ezer Vierba leads an expository freshmen writing course on “Buddhism, Mindfulness, and the Practical Mind,” and Metta McGarvey teaches “Mindfulness for Educators” at the Graduate School of Education.

Due to high demand, McGarvey, who holds a doctorate in human development and psychology, teaches a three-day workshop for educators. It offers tools to enhance their work and their focus through breathing practices and self-compassion exercises.

“A lot of them are working in really tough environments, with all kinds of pressures,” said McGarvey. “The rates of burnout in some of the more challenging environments are very high.”

Ayesha Hood, a police officer from Baltimore who is interested in running a day care center, attended McGarvey’s workshop last fall, and found it helpful. “As a police officer, I live in high stress, and as a public servant, I tend to neglect myself,” she said. “I want to calm myself and be conscious about it.”

Christine O’Shaughnessy, a former investment bank executive who lead workshops at Harvard, said, “All day we’re bombarded with social media, colleagues, work, children, etc. We don’t have time to spend it in quiet reflection. But if you practice it at least once a day, you’ll have a better day.”

To skeptics who still view mindfulness as hippie-dippy poppycock, O’Shaughnessy has four words: “Give it a try.” When she first signed up for a mindfulness workshop in 1999, she said she was skeptical too. But once she realized she was becoming calmer and less stressed, she converted. She eventually quit her job and became a mindfulness instructor. (She recently launched a free meditation app.)

“Doing mindfulness is like a fitness routine for your brain,” she said. “It keeps your brain healthy.”

Metta McGarvey teaches the practice of mindfulness, a workshop for educators inside the Gutman Conference Center.

Kris Snibbe/Harvard Staff Photographer

Mindfulness practitioners admit the practice can offer challenges. It requires consistency because its effects can be better felt over time, and discipline to train the wandering mind to keep coming back to the present, without judgment. A 2014 study said that many people would rather apply electroshocks to themselves than be alone with their thoughts. Another study showed that most people find it hard to focus on the present and that the mind’s wandering can lead to stress and even suffering.

Despite the rising acceptance of mindfulness, many people still think the practice involves emptying their minds, taking mini-naps, or going into trances. Beginners often fall asleep, feel uncomfortable, struggle with difficult thoughts or emotions, and become bored or distracted. Adepts recommend practicing the process in a group with an instructor.

After the training session led by Westbrook, one participant said she couldn’t stop thinking about what was for dinner during the meditation practice; others nodded in agreement. Westbrook reassured her, saying that mindfulness is not about stopping thoughts or emotions, but instead about noticing them without judgment. Mindfulness builds resilience and awareness to help people learn how to ride life’s ups and downs and live happier and healthier lives, said Westbrook, who, after helping heal the bodies of thousands of patients in 36 years as a doctor, plans to devote her second career to caring for people’s spirits and souls, maybe as a chaplain.

“Mindfulness is not about being positive all the time or a bubblegum sort of happiness — la, la, la,” she said. “It’s about noticing what happens moment to moment, the easy and the difficult, and the painful and the joyful. It’s about building a muscle to be present and awake in your life.”

For more information about the Mindfulness & Meditation program at Harvard University, visit its website. For a list of spring courses for Harvard faculty and staff, visit the Mindfulness at Work Program website.