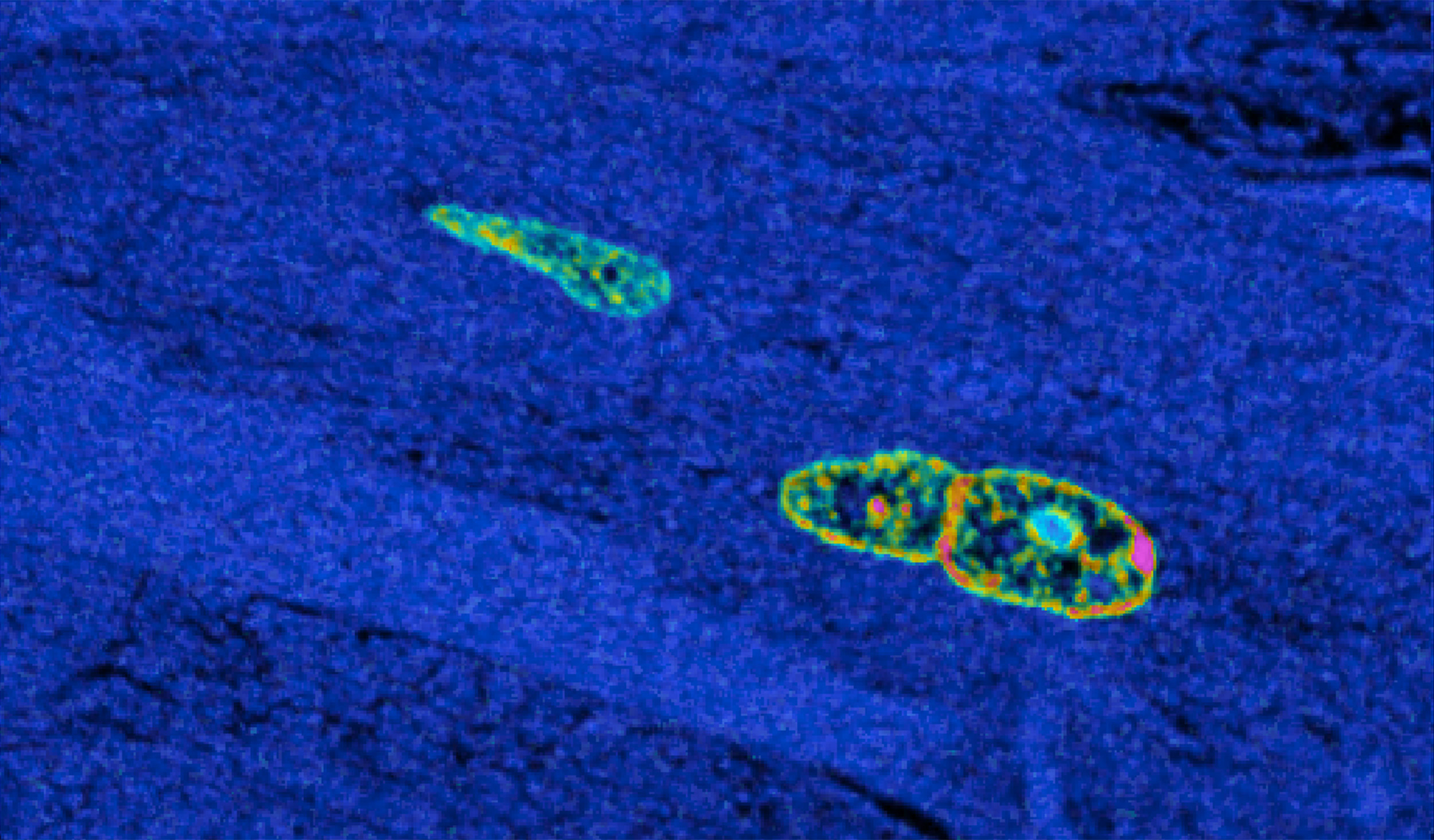

Heart muscle cells, viewed using multi-isotope imaging mass spectrometry (MIMS). Pink shows where new DNA is being produced in the dividing cell nucleus, indicating growth of heart muscle tissue.

Image courtesy of Ana Vujic/HSCRB

Exercise may help make heart younger

Active mice make more than four times as many new heart muscle cells, study says

Doctors, health organizations, and the U.S. surgeon general all agree that exercise is good for the heart. But the reasons why are not well understood.

In a new study performed in mice, researchers from the Harvard Department of Stem Cell and Regenerative Biology (HSCRB), Massachusetts General Hospital (MGH), Harvard Medical School (HMS), and the Harvard Stem Cell Institute (HSCI) uncovered one explanation for why exercise might be beneficial: It stimulates the heart to make new muscle cells, both under normal conditions and after a heart attack.

Just published in the journal Nature Communications, the findings have implications for public health, physical education, and the rehabilitation of cardiac patients.

The human heart has a relatively low capacity to regenerate itself. Young adults can renew around 1 percent of their heart muscle cells every year, and that rate decreases with age. Losing those cells is linked to heart failure, so interventions that increase cell formation have the potential to help prevent it.

The two first authors on the study were Ana Vujic of HSCRB and Carolin Lerchenmüller of MGH and HMS. Vujic said, “We wanted to know whether there is a natural way to enhance the regenerative capacity of heart muscle cells. So we decided to test the one intervention we already know to be safe and inexpensive: exercise.”

To test its effects, the researchers gave one group of healthy mice voluntary access to a treadmill. When left to their own devices, the mice ran about 5 kilometers each day. The other healthy group had no such gym privileges, and remained sedentary.

To measure heart regeneration in the mouse groups, the researchers administered a labeled chemical that was incorporated into newly made DNA as cells prepared to divide. By following the labeled DNA in the heart muscle, the researchers could see where cells were being produced. They found that the exercising mice made more than 4.5 times the number of new heart muscle cells as did the mice without treadmill access.

The results were significant, but were they relevant? To find out, the researchers brought the experiment a little closer to home.

“We also wanted to test this in the disease setting of a heart attack, because our main interest is healing,” said Vujic.

After experiencing heart attacks, mice with treadmill access still ran 5 kilometers a day, voluntarily. Compared with their sedentary counterparts, the exercising mice showed an increase in the area of heart tissue where new muscle cells are made.

The conclusion was that in mice, exercise means regenerating heart tissue — a lot of it.

The two senior authors behind the study were Richard Lee, Harvard professor of stem cell and regenerative biology and a principal faculty member of HSCI, and Anthony Rosenzweig, Paul Dudley White Professor of Medicine at HMS, chief of the cardiology division at MGH, and a principal faculty member of HSCI.

“Maintaining a healthy heart requires balancing the loss of heart muscle cells due to injury or aging with the regeneration or birth of new heart muscle cells. Our study suggests exercise can help tip the balance in favor of regeneration,” said Rosenzweig.

“Our study shows that you might be able to make your heart younger by exercising more every day,” said Lee.

It’s all very well to say that exercise is good for the heart, but how does that actually work? The researchers plan to pinpoint which biological mechanisms link exercise with increased regenerative activity in the heart.

“If we can turn on these pathways at just the right time, in the right people, then we can improve recovery after a heart attack,” said Lee.

This research was supported by the National Institutes of Health, the American Heart Association, the Leducq Foundation, and the German Research Foundation.