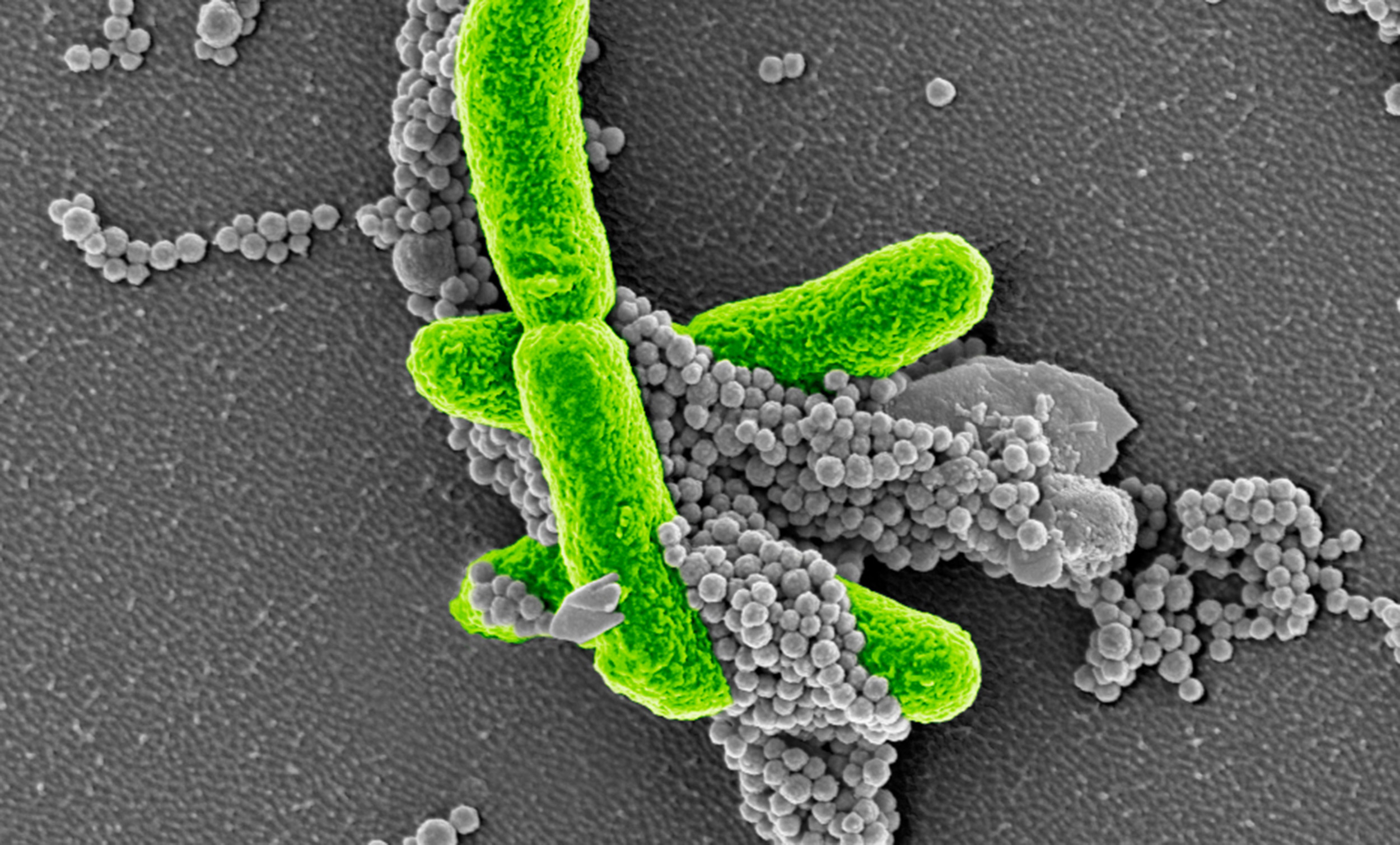

The new swine-specific sepsis assessment criteria could allow researchers to better evaluate infection and more accurately track the effect of potential sepsis treatments in preclinical pig models. The image shows E. coli (green) bacteria captured by FcMBL magnetic beads (gray spheres).

Credit: Wyss Institute at Harvard University

A new model for an old killer

After 30 years, scientists closer to finding sepsis treatment

Sepsis, or blood poisoning, occurs when the body’s response to infection damages its own tissues and organs, leading to organ failure. It kills millions each year worldwide, and is the most common cause of death in people who have been hospitalized. Despite its prevalence, the standard treatment is to give patients antibiotics and fluids, and no new therapies have been developed in the last 30 years due to the high failure rate of sepsis treatments in clinical trials.

The animals typically used to test drug candidates in preclinical trials (mice and baboons) are poor proxies for human responses to sepsis, as they are frequently resistant to the pathogens that cause sepsis-inducing infections. Pigs are a much better model organism, as their immune systems and humans’ share 80 percent of the same machinery, their blood clotting is similar, and their large size allows their vitals to be monitored in real time. However, even in pig studies, the animals’ responses to sepsis are not currently measured with the same criteria used in human clinical practice, largely because research facilities lack the personnel, equipment, and clinical facilities needed to perform the required tests on multiple animals.

To address this problem, a team of scientists from the Wyss Institute at Harvard University and Boston Children’s Hospital has created a new approach for clinical monitoring designed to measure sepsis responses in pigs. Analyzing pigs based on multiple physiological signs as well as organ failure, rather than death, could help provide a more accurate preview of a sepsis drug’s effect on humans before it reaches clinical trials. The research is reported in Advances in Critical Care Medicine.

“… no new therapies have been developed in the last 30 years due to the high failure rate of sepsis treatments in clinical trials.”

Human cases of sepsis are evaluated based on a 2016 protocol called that uses Sequential Organ Failure Assessment (SOFA) scoring criteria to classify the severity of sepsis by incorporating measurements of heart, kidney, liver, lung, brain, and blood clotting function, as sepsis leads to the failure of multiple organs. Typically, animal models are evaluated by whether the animal dies as a result of illness, with the exact cause only being determined at autopsy. Inspired by the Sepsis-3 assessments used clinically, the researchers created a swine-specific Sepsis-3 (ss-Sepsis-3) protocol with swine-specific SOFA (ss-SOFA) scoring criteria so that they could evaluate sepsis in living infected pigs in a manner that mirrored human clinical assessment.

“Our system goes beyond simply measuring the effects of pathogen injection on inflammation and animal survival. Because it mimics the life-threatening organ failure that is also seen in sepsis patients, it also might provide a better prediction of how sepsis therapies will perform in humans,” said Mike Super, lead senior staff scientist at the Wyss Institute and co-author of the paper.

Anna Waterhouse, a former research scientist at the Wyss Institute, collaborated on the study with a surgical team led by Boston Children’s Hospital’s senior veterinarian, Arthur Nedder. They infused E. coli bacteria into the blood of 18 young Yorkshire pigs and used the new protocols to evaluate the responses of their various organs in real time. Six pigs were given the bacteria while conscious, six while under anesthesia, and six did not receive E. coli but underwent the same procedures (four conscious and two anesthetized). The scientists found that increases in the total ss-SOFA scores among both conscious and anesthetized pigs were largely due to kidney and blood clotting failure, with two of the conscious animals developing acute kidney failure.

Three of the anesthetized animals were categorized as experiencing septic shock (the highest severity level in the ss-SOFA system), based on a combination of those organ failures as well as anesthesia-induced heart failure and the lack of a fever due to lowered body temperature. These results suggest that the effects of anesthesia need to be taken into account when evaluating responses to sepsis.

Real-time monitoring of animals, whether alive or anesthetized, requires a significant investment of personnel and time, but being able to more closely replicate and study human sepsis responses could have significant benefits for drug development and testing.

“Our modified pig-specific SOFA scoring approach based on the Sepsis-3 guidelines lays the foundation for future studies that can quantify the severity of sepsis when evaluated with longer time frames, different pathogen strains, and antibiotic treatments, as well as comorbidities that typically accompany sepsis in human patients,” said corresponding author and Wyss Founding Director Donald Ingber, who is also the Judah Folkman Professor of Vascular Biology at Harvard Medical School and the Vascular Biology Program at Boston Children’s Hospital, as well as professor of bioengineering at the Harvard John A. Paulson School of Engineering and Applied Sciences (SEAS).

Additional authors of the study are current and former Wyss Institute researchers, including Daniel Leslie, Dana Bolgen, Shanda Lightbown, Nikolas Dimitrakakis, Mark Cartwright, Benjamin Siler, Kayla Lightbown, Kelly Smith, Patrick Lombardo, Julia Hicks-Berthet, and Boston Children’s Hospital researchers Sam Jurek and Kathryn Donovan.

This research was supported by DARPA and Harvard’s Wyss Institute for Biologically Inspired Engineering.