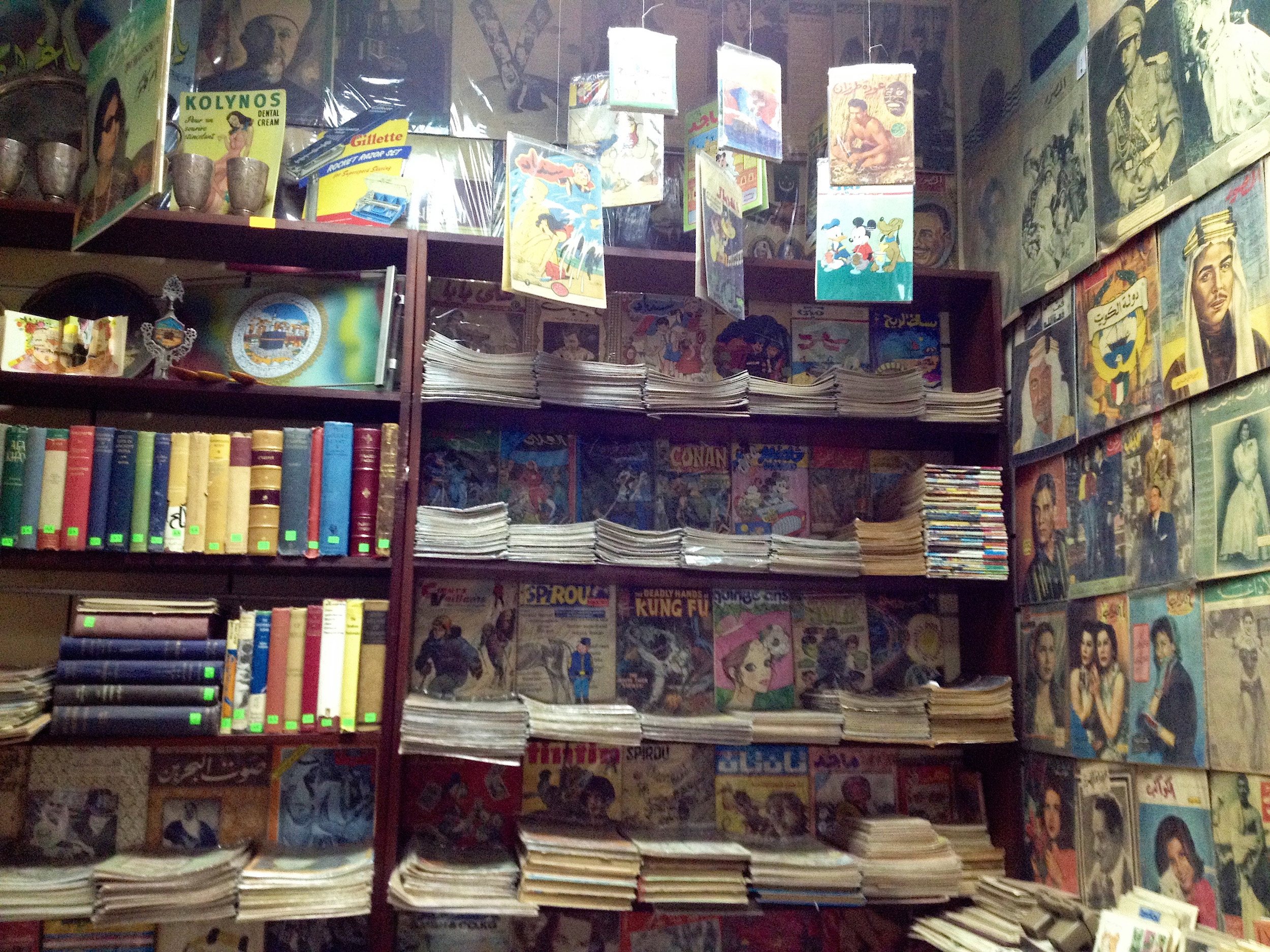

A shop in Cairo’s Khan Al-Khalili that specializes in rare magazines, newspapers, and ephemera.

Photo by Jonathan Guyer

Inspired by Cairo

Radcliffe fellow sees reflections of Arab Spring in comic art revolution

Jonathan Guyer, RI ’18, an independent journalist and contributing editor of the policy journal Cairo Review of Global Affairs, has spent the past five years researching Arabic comics. To that end, he has interviewed many graphic artists and translated hundreds of their cartoons. He is now writing a book about what he’s calling the “new wave” of comic art that has swept the Middle East and North Africa in the past 10 years.

Q&A

Jonathan Guyer

RADCLIFFE: Who are your heroes?

GUYER: I admire the tenacity of many journalists I have met across the Middle East, far too many to name. One example that comes to mind is the team at Egypt’s last remaining independent news outlet, Mada Masr, which authorities currently block access to within the country. They work against all odds, investigating ministries and institutions that seek to be opaque. In the face of existential threats — Egypt is the third-worst jailer of journalists in the world, after Turkey and China — Mada continues to publish daily.

RADCLIFFE: Best personality trait?

GUYER: I’d like to think it’s my enthusiasm or ruthlessness, but it’s probably my passion for the sartorial delights. Growing up, my dad used to take me on runs to his favorite haberdasheries and tailors on weekends rather than Sunday football games. Is being fashionable a personality trait?

RADCLIFFE: Who is your muse?

GUYER: Cairo. The city of 20 million has been my source of inspiration for a decade. Of course, there is a gendered dynamic to the notion of the muse, and I don’t totally feel comfortable with gendering such a diverse metropolis. Indeed, local artists have personified Egypt as a woman for a century or more. In the process, ideas of womanly honor and idealized feminism are activated, which demand further inquiry and serious criticism (Beth Baron, in her book “Egypt as a Woman: Nationalism, Gender, and Politics” [University of California Press, 2007], began this important conversation). Nevertheless, Cairo has been the engine of my ideas. I owe the city everything.

Image 1: Political cartoons figure prominently in the Arab Press, and Anwar is among Egypt’s best known cartoonists. Here he offers universal commentary on free speech. Image 2: An eye-catching drawing by Egyptian artist Tawfig from the 2015 exhibition “The Good, the Bad and the Crimson Shoe” at Cairo’s Medrar gallery. Tawfig has contributed to Arab comic zines and draws political cartoons for news outlets.

Anwar, Al-Masry Al-Youm (2016); Tawfig (2015)

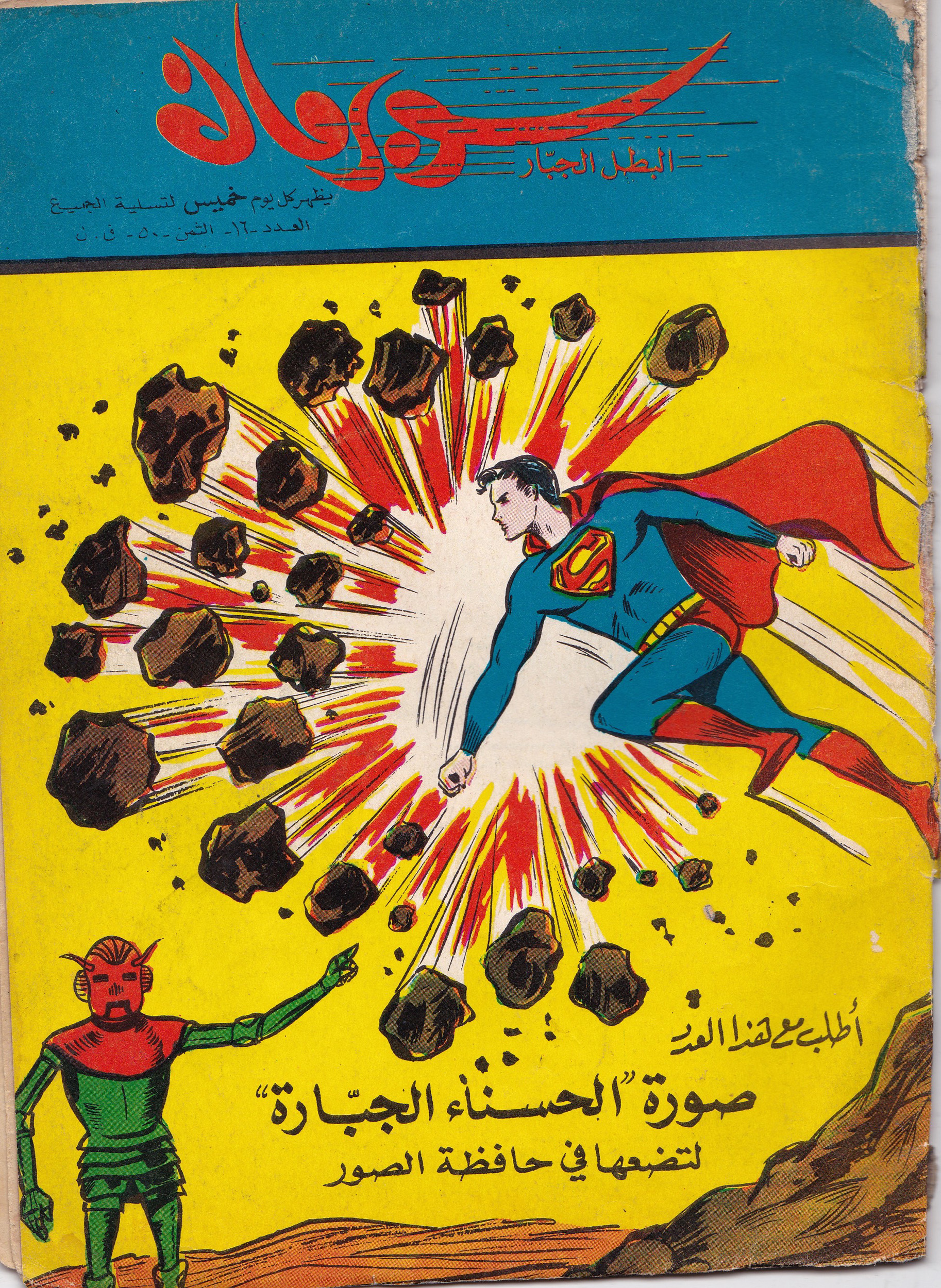

Image 1: The the first issue of the popular midcentury Egyptian children’s magazine Sindibad, with comics, puzzles, and games. Its creator, Hussein Bicar (1913-2002), is also one of Egypt’s great modern painters. Image 2: An early Arabic translation of Superman.

Hussein Bicar. Sindibad No. 1 (Cairo, 1952); Superman No. 16 (Beirut, undated circa 1966)

RADCLIFFE: Tell us your favorite memory.

GUYER: When I worked as a Mideast researcher in D.C., I staffed a swanky invite-only event at the illustrious Café Milano. By 10 p.m., my bosses had already left. I found myself at a long table drinking champagne with Quincy Jones. He recounted Aretha Franklin’s birthday party on a yacht in Detroit. How I wish I had asked him about producing “Thriller.”

RADCLIFFE: Describe yourself in six words or fewer.

GUYER: Don’t forget your Panama hat!

RADCLIFFE: What is your most treasured possession?

GUYER: The first issue of the Paris Review, from 1953. I found it at the infamous John King Books in Detroit.

RADCLIFFE: What inspires you?

GUYER: Those who can maintain a sense of humor in the face of adversity and conflict.

RADCLIFFE: Name a pet peeve.

GUYER: Credit-card payments at corner stores and local establishments. Carry cash, people. You’re really going to charge a cup of joe?

RADCLIFFE: Were your life to become a motion picture, who would portray you?

GUYER: The dream: Paul Rudd. The reality: Jason Schwartzman. And if the director knew me well: Larry David.

RADCLIFFE: Where in the world would you like to spend a month?

GUYER: Argentina. I have been taking tango lessons on and off for three years, but I’m still a novice. I need to practice.

RADCLIFFE: What is your greatest triumph so far?

GUYER: The fact that I’ve managed to get my facility in Arabic up to a level where I can be as spontaneous as I am in English, or at least fake it. Over the past year, I have interviewed poets and novelists in Arabic and even appeared on live radio on BBC Arabic. The sophomore version of me, conjugating verbs and studying word lists, could never have imagined it.

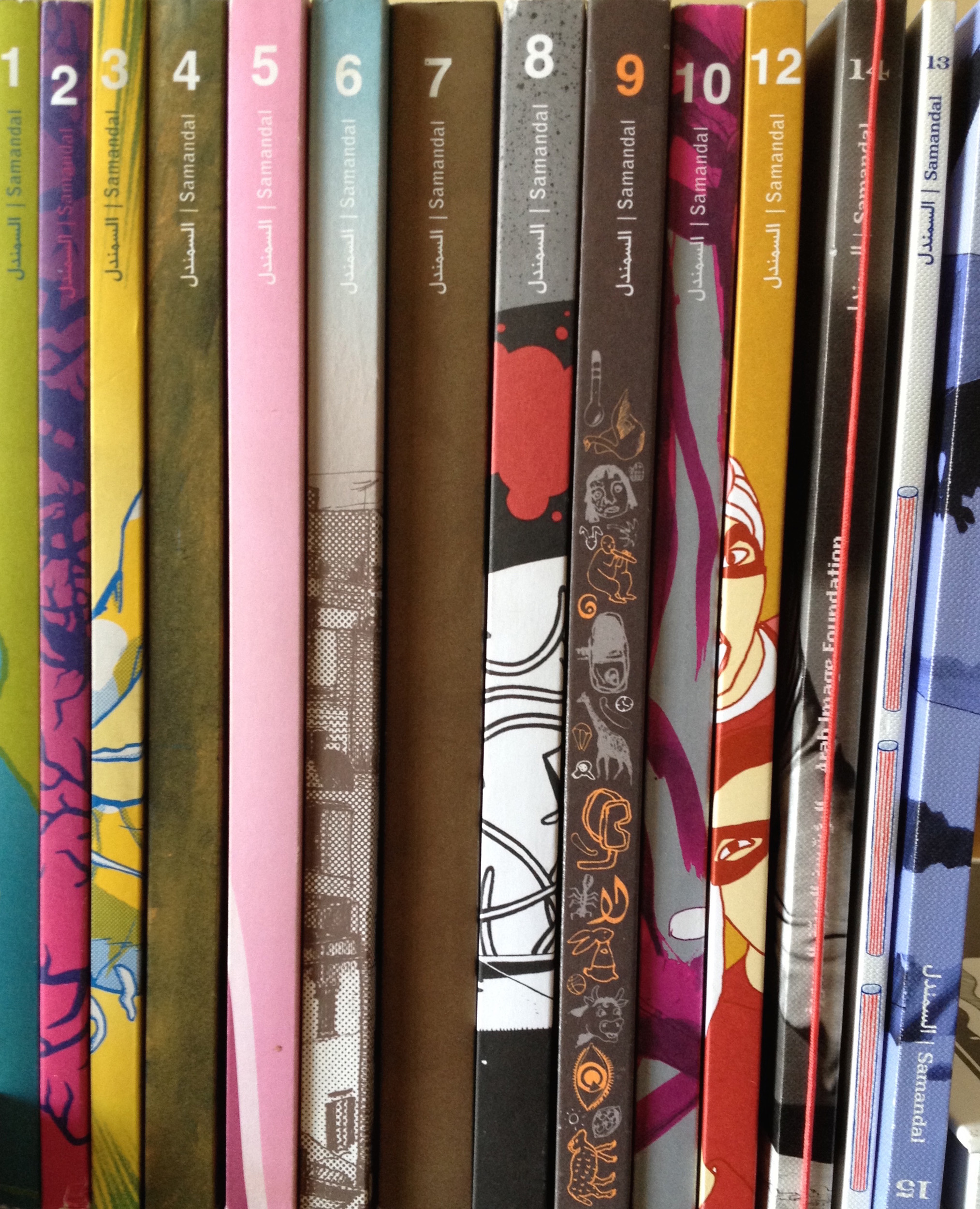

Image 1: Spines of the Lebanese comic zine Samandal, or Salamander in English, which pushed the envelope in Lebanon since its first issue in 2007. Image 2: This comic tells the story of a car valet who stumbles upon a sobbing Chinese girl in a downtown Cairo alley. Despite the language barrier, he decides to bring the lost girl to his family home, and he hails a taxi. These elegant cityscapes first appeared in a 2012 issue of the ‘zine Tok Tok, a collaborative and experimental graphic publication that has put out 14 issues since 2011.

Photo by Jonathan Guyer; Shennawy, Tok Tok No. 6 (Cairo, 2012)

RADCLIFFE: Whose tunes do you enjoy?

GUYER: Lately, I’ve been trapped in the ’60s, listening to Joni Mitchell, the Beach Boys, the Band, and Dylan. But I’m a Detroiter, so Motown is in my blood and the White Stripes are my anthem. For deep cuts, I am always hooked on classic blues, like the work of Blind Willie McTell and Memphis Minnie, as well as big-band jazz.

RADCLIFFE: What is your fantasy career?

GUYER: Honestly — and I’m pinching myself here — it’s what I’m doing right now. How many people get to write about comics for a living?

RADCLIFFE: What is the most challenging aspect of being a Radcliffe fellow?

GUYER: Sharing the glories of the ivory tower with those outside the Harvard orbit. I am eager to help scholars abroad at risk, for instance, and there is a particular urgency in countries like Turkey. When I attended an academic conference in Istanbul a month before the failed coup attempt of 2016, the situation was already tenuous, and since then, it has exacerbated considerably. The challenge is how to go beyond our research projects and contribute to something that isn’t just another book or paper.

Inside the offices of the Egyptian children’s magazine Samir, which has published comics for more than 60 years.

Photo by Jonathan Guyer

RADCLIFFE: What drew you to Arab comics and graphic novels?

GUYER: I have always been an amateur illustrator. In college, I served as cartoonist for the Brown Daily Herald and the American University in Cairo’s student newspaper, Caravan. I kept drawing for blogs while working as an editor and researcher in Washington, D.C. So when the Arab revolutions broke out in 2011, I wondered what Arab cartoonists were thinking and doing. I made a research plan and applied for a Fulbright. Little did I know that graphic novels, a relatively new medium, were budding in Cairo and Beirut and, more recently, across North Africa.

RADCLIFFE: What do these visual forms reveal about the Arab political climate?

GUYER: Even if many of the comics in question are not overtly political, the emergence of alternative comics and graphic novels in the Arab world in the past decade reflects many of the political ideas of the 2011 revolutions. In the many horizontal comic collectives that put out illustrated ’zines, one can see radical politics, experimental narrative techniques, and new aesthetic approaches in the drawings and compositions. There is also a particular interest in urban environments, which again reflect the ethos of the so-called Arab Spring protests and their anchoring within the city fabrics of Cairo and beyond.

RADCLIFFE: What’s the importance of this art form to those producing and consuming it?

GUYER: Comic strips and political cartoons have been around for over a century in Arabic, but the newness of Arab graphic novels and alt-comics is incredibly liberating for artists. While they draw upon the local visual and literary traditions, they also have the space to experiment freely. Comic artists in the Middle East are pushing the envelope and the boundaries of the art form, and readers eagerly consume these countercultural products. Sure, censorship regimes endure in many Arab states through laborious legal frameworks, and the threats are real. Yet the scores of artists I have interviewed are scarcely deterred by intimidation from governments or extremists. In the meantime, their illustrated works are inspiring youngsters to pick up pens and try their hands at telling their own singular stories.