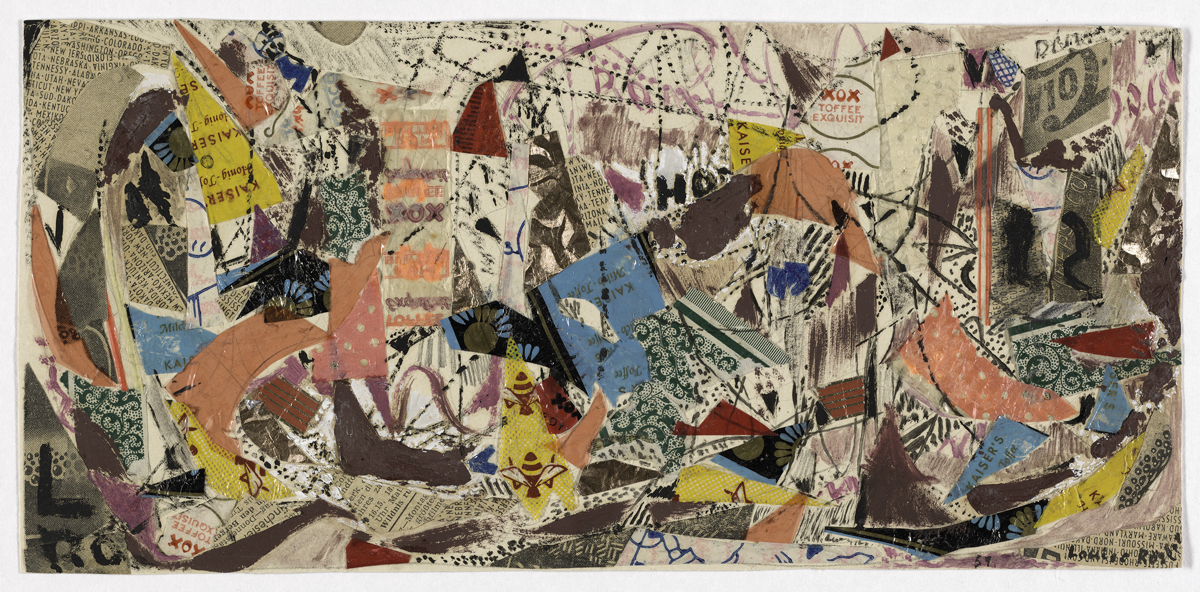

“Street” by Louise Rösler. American soldiers stationed in Germany after World War II dropped candy wrappers in the street in the artist’s small town outside Frankfurt, and she began using them in collage.

Harvard Art Museums/Busch-Reisinger Museum, Purchase through the generosity of Renke B. Thye

Visions pursued through darkest shadows

‘Inventur’ shines light on work by German artists during and after World War II

In 1930s Germany, modern art collided with Nazi hate. Works by abstract pioneers clashed with the classical tradition that fed Adolf Hitler’s Aryan fervor, and contemporary works were stripped from German museums. Munich’s “Degenerate Art Exhibition” of 1937 famously mocked a range of designs. Many artists lost their teaching positions and were banned from practicing. Yet many continued to create in secret, and their output blossomed after the war.

Now some of those creations are on view at Harvard.

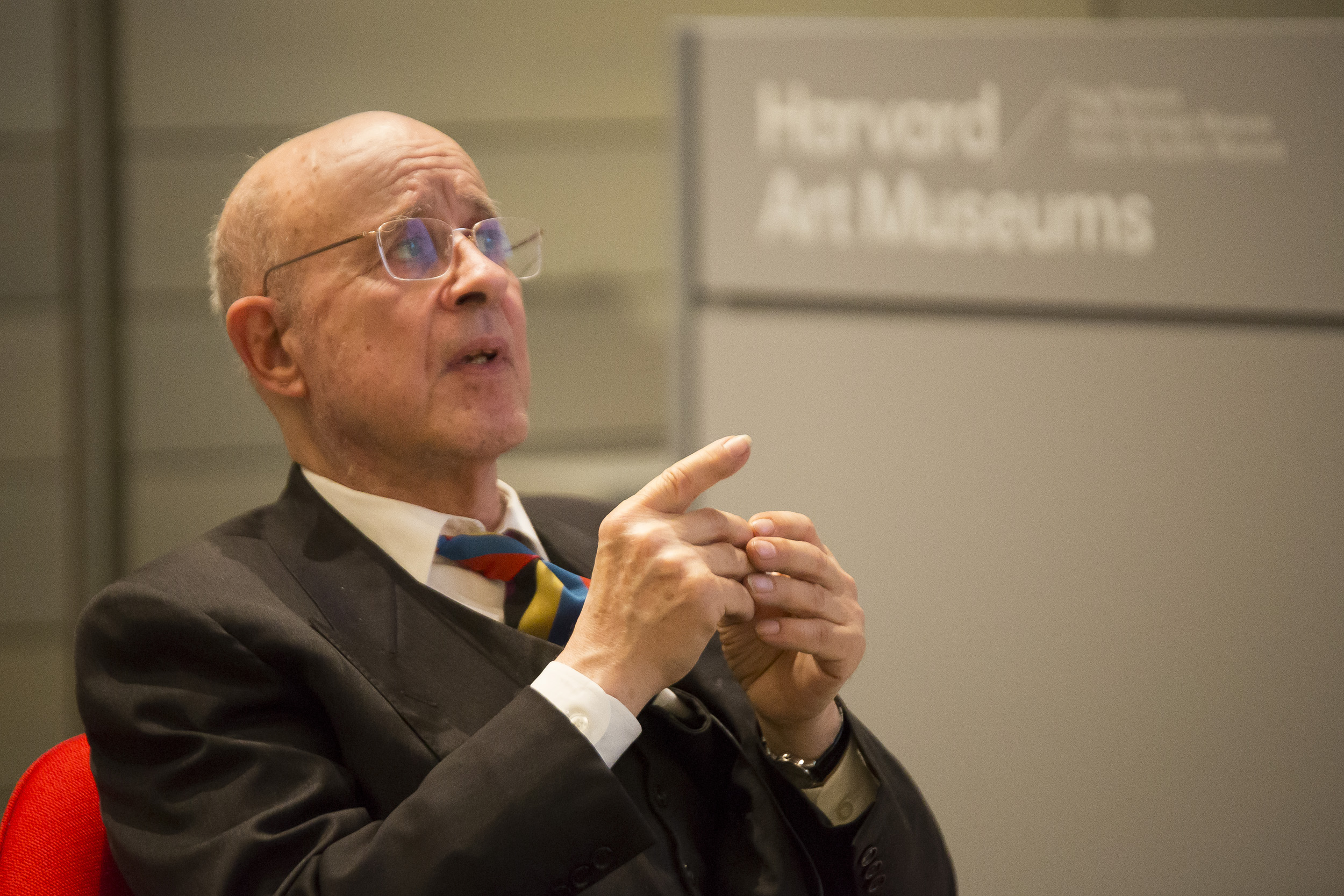

“These are modern artists who for the most part could not work or exhibit publicly during the Nazi period,” said Lynette Roth, curator of “Inventur — Art in Germany, 1943‒55,” on view at the Harvard Art Museums through June 3. The show explores an era of German art-making that has drawn scant attention from American art historians and museums, said Roth, the Daimler Curator of the Busch-Reisinger Museum. But the more than 160 works by close to 50 artists, ranging from photographs and paintings to sculpture and collage, document a 12-year span marked by creativity, invention, and national torment.

Lynette Roth curated a new exhibit, “Inventur — Art in Germany, 1943‒55,” on view at Harvard Art Museums through June 3.

Jon Chase/Harvard Staff Photographer

Inventur — “inventory” in English — suggests a “physical and moral” stock-taking, Roth notes in the show’s catalog, as German artists re-examined and reinvented their work while grappling with “the aftermath of the atrocities of World War II and the Holocaust, Germany’s defeat and occupation by the Allies, and social and economic circumstances enacted through currency reform.”

Scholars understand that there are difficult dimensions to the show. They note that the narratives of the featured artists represent a range of wartime experiences, including both conscription into the war effort and fierce opposition to Nazi rule. They also point to the historical significance of work that inspired future artists and movements.

“I am intrigued by the question of why historians have been able to delve in and really look at what happened in that decade, but art historians and museums largely have not,” said Martha Tedeschi, the Elizabeth and John Moors Cabot Director of the Harvard Art Museums. “We recognize there are some potentially very controversial conversations to be had around this topic. But there is no doubt that modern art in Germany was re-emerging from the rubble of World War II during this understudied yet extraordinarily generative 12-year period.”

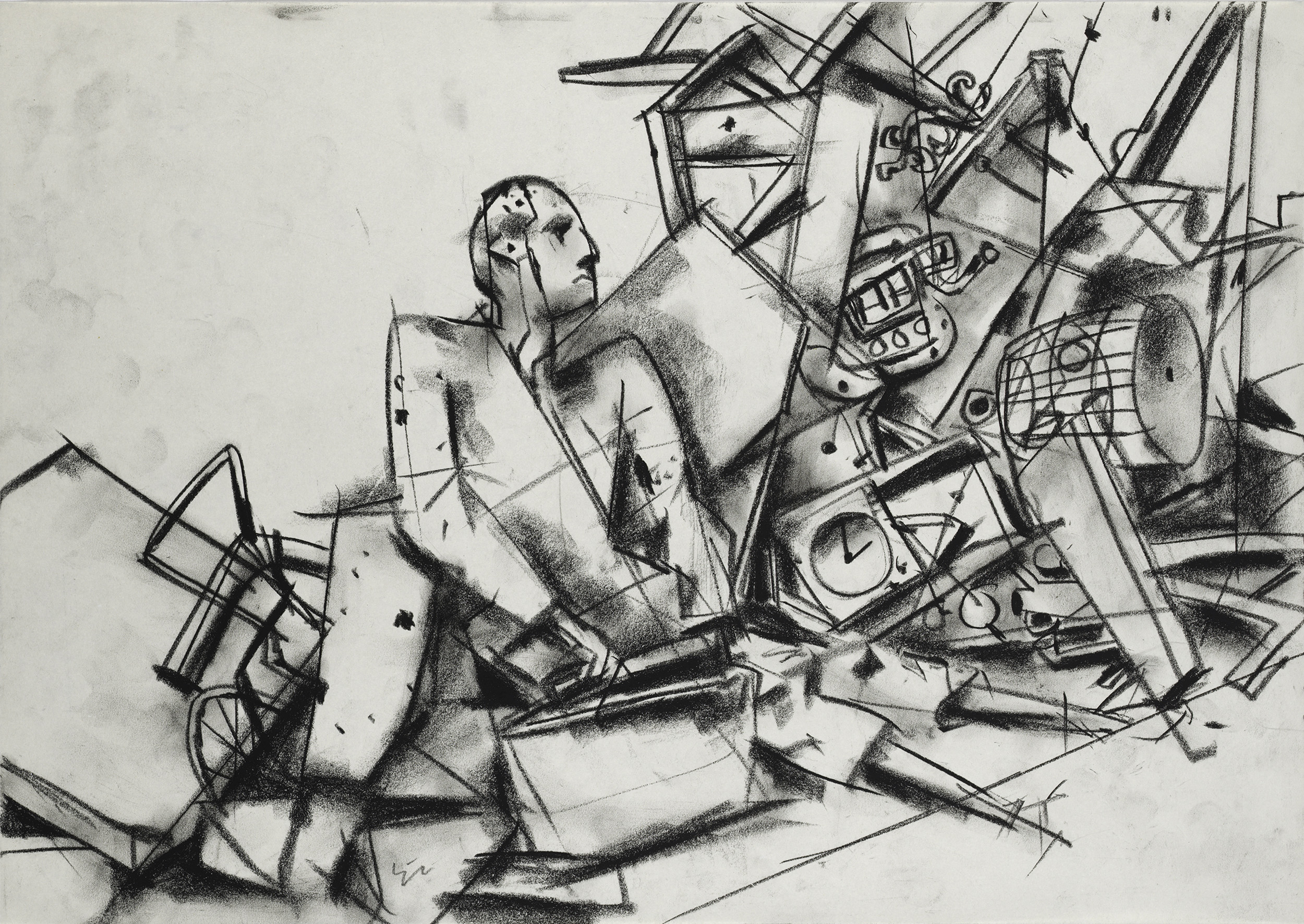

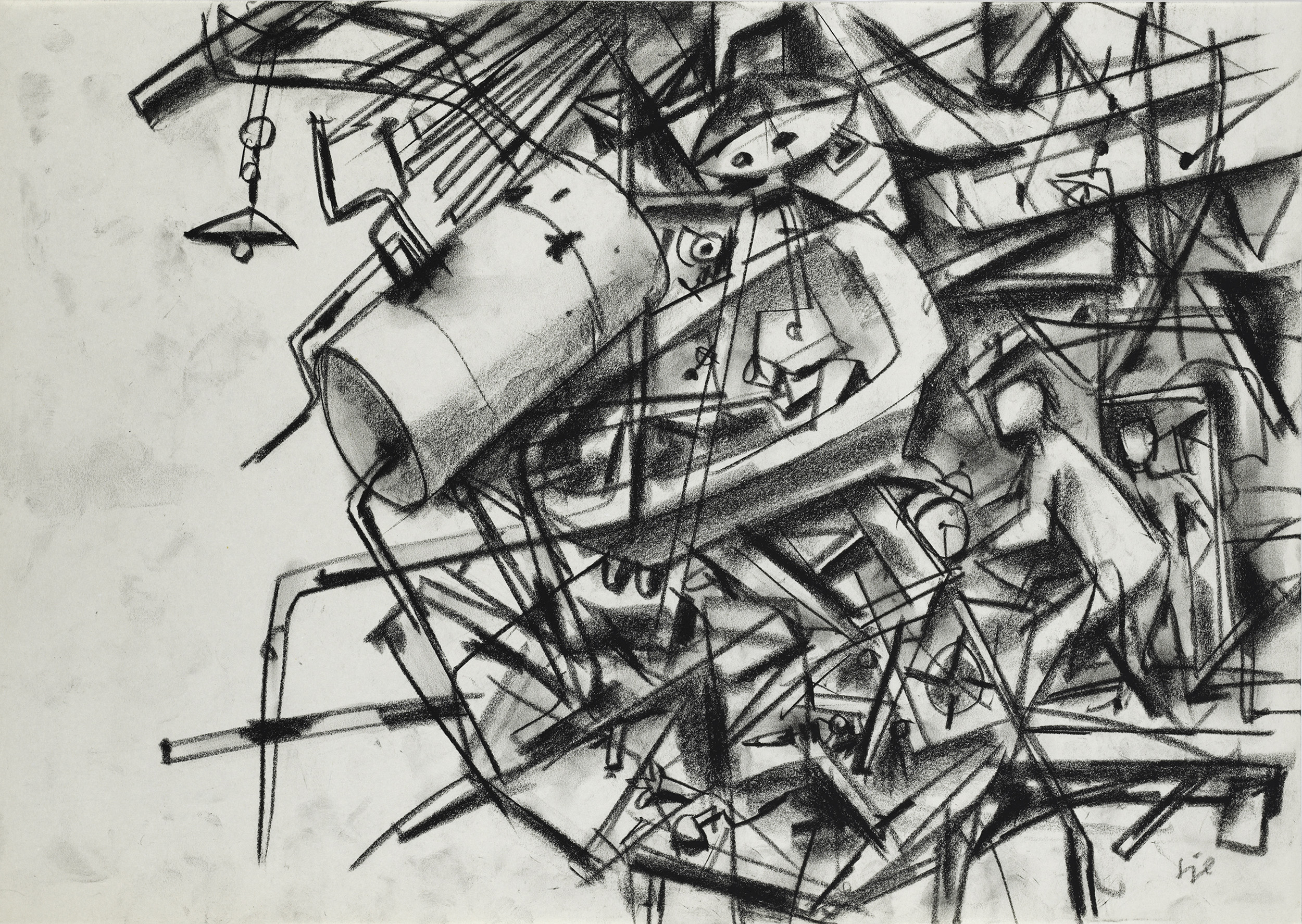

Works from the early to mid-1940s reflect the effects of the war on the private lives of the artists who stayed behind. The defeat of German forces at Stalingrad in 1943 marked a turning point in the war whose effects included a rise in Allied bombings in Germany, and many of the show’s early images capture the devastation. One such work is Erwin Spuler’s “As the Fire Fell From the Sky,” a pair of drawings from 1945 and 1946 in black chalk on white wove paper.

Erwin Spuler’s drawings “As the Fire Fell From the Sky.”

© President and Fellows of Harvard College

“The war is literally happening at their front door, and the ruin itself, which is really the marker in postwar Germany of the war, has become a part of everyone’s daily lives,” said Roth.

Scarcity of materials meant artists used whatever they could find. Karl Hartung’s 1948 sculpture “Free Form” was created with stone salvaged from a local train station.

“The debris of the war became the material of the artist to a great extent,” said Tedeschi.

The show also highlights the work of “female artists who had fallen out of the narrative,” said Roth, including a series of brightly colored abstract pieces by Louise Rösler from 1951 featuring tinfoil and cellophane. American soldiers stationed in Germany after the war dropped candy wrappers in the street in her small town outside Frankfurt, and Rösler began using them in collage.

In the 1950s, as the German economy began to rapidly rebound, many artists forged relationships with the industrial and commercial worlds, including photographer Peter Keetman, whose series of evocative shots snapped at the Volkswagen factory in Wolfsburg in 1953 are part of the exhibition.

At an event this month marking the opening of the exhibit, Roth spoke with the only featured artist still living, Konrad Klapheck, whose best-known works are pop art- and surrealist-inspired depictions of mechanical items such as sewing machines and typewriters.

Konrad Klapheck, the only artist featured in the exhibit who is still living, spoke at its opening event.

Photo by Schippert+Martin Photography

“What I have to say, what I can give you, is honest and authentic,” Klapheck told the capacity crowd at Menschel Hall.

Born in Düsseldorf in 1935, “when Nazis had taken full power of every part of the German people,” Klapheck fled with his mother to Eastern Germany during the war. When they returned home in 1945, abstraction was emerging as the “leading modern art style.” Wary of competing with abstract masters such as Piet Mondrian and Jackson Pollock, and inspired by the work of German figurative artist Bruno Goller, Klapheck turned his efforts in art school to “making one isolated object the subject of a painting.”

One of Klapheck’s iconic typewriter paintings is part of the Harvard exhibition, as is his 1950 vision of a war-torn German town, “Landscape with Ruins.”

Klapheck made “Landscape with Ruins” in 1950.

© 2017 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York/VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn

In discussing the Germany of his youth, the 83-year-old said “a few gifted artists sold their soul to the devil, blinded by the idea of fame and fortune,” but others either fled, or tried to resist the Nazi regime. The latter included his father, a teacher at the art academy in Düsseldorf. When his colleagues insisted he salute Hitler, Klapheck’s father responded with a joke and was soon fired “for lack of national spirit.”

“In a way it was the mercy of God, the mercy of heaven,” said Klapheck, “that my father died in 1939.”