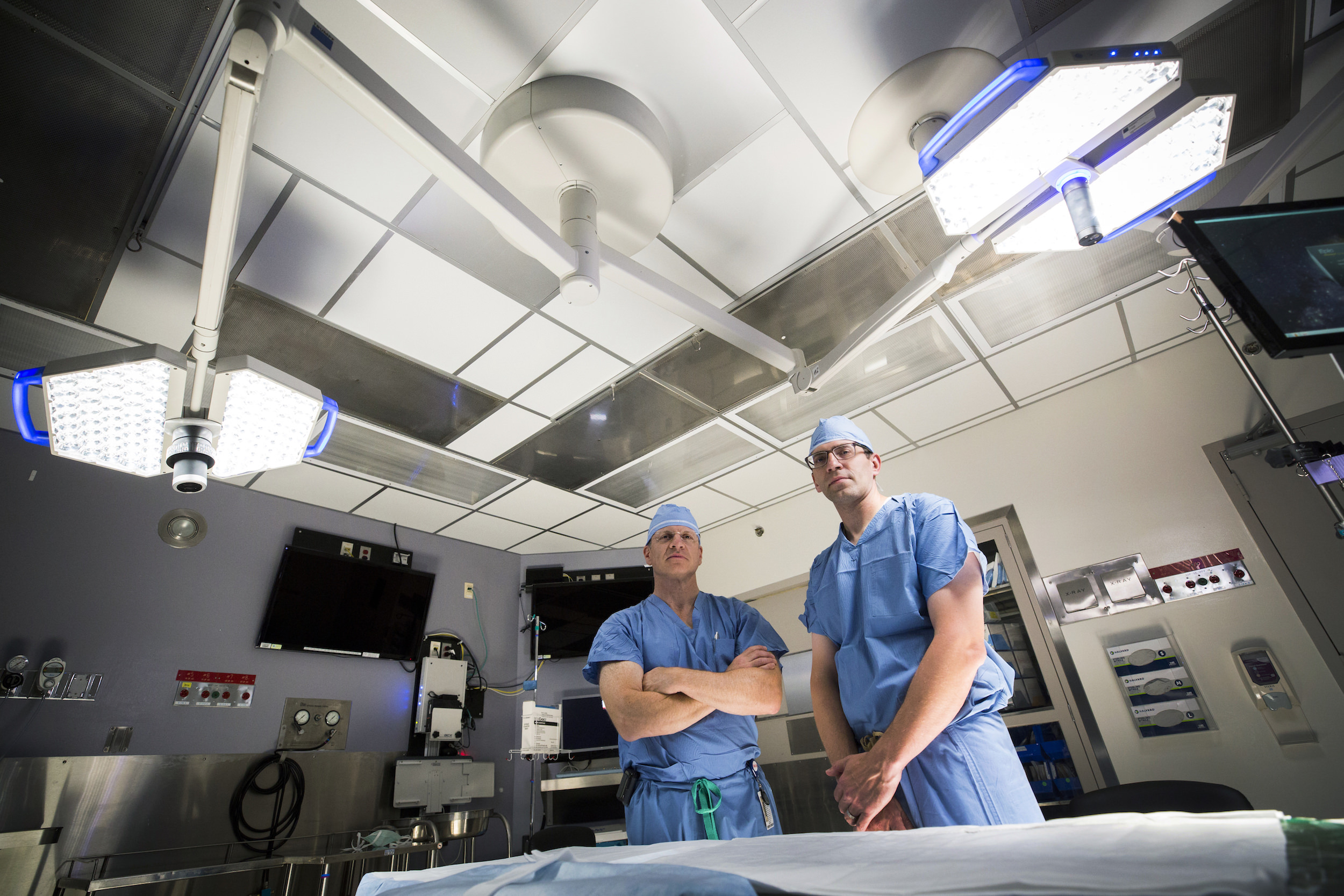

MGH physicians Allan Goldstein (left) and Brian Cummings were faced with ethical and surgical challenges when they separated conjoined twins.

Stephanie Mitchell/Harvard Staff Photographer

For family, doctors, life and death were inseparable

Wrenching decision at MGH: ‘We probably knew there was no hope and yet I just maintained hope the whole time’

Doctors knew from the start that the procedure wasn’t going to be easy, but when images showed the patients’ tangled insides, they realized that more than a surgical challenge lay ahead.

It was 2016 and a team at MassGeneral Hospital for Children was examining 22-month-old twin girls conjoined at the abdomen and pelvis whose parents had brought them from East Africa to Boston in search of physicians willing and able to take on the profound complexities of separation surgery.

The girls’ care over the following weeks involved some 200 people — physicians, nurses, social workers, technicians, and religious leaders — and a single, searing question: When — if ever — is it OK to sacrifice one life to save another?

The parents, who have requested anonymity, had the final say. But doctors and other hospital personnel, no strangers to illness and death, were plunged into a wrenching examination of both their personal values and the responsibilities of their profession: the obligation to do no harm, the duty to act to save a life, and what happens when those concepts conflict.

“My 14-year-old daughter just asked me … ‘Did you violate the Hippocratic oath?’” said Allan Goldstein, who directed the procedure as the hospital’s surgeon in chief. “I said, ‘First, thank God you’re not a reporter. And second, it’s a great question and I don’t know the answer.’”

Goldstein, also professor of surgery at Harvard Medical School (HMS), got involved in the case when he was contacted by a nonprofit on behalf of the parents, who had struggled to find physicians with the expertise to separate the twins.

The search had come up empty in their home country, where stigma attached to the girls’ condition had made it difficult to take them out of the house, according to a recent report in the New England Journal of Medicine. After the parents shifted their focus to the U.S., some 20 institutions turned them down before Goldstein answered the phone.

“Maybe if you asked me, purely on an intellectual level, I would have admitted there was no hope, but I didn’t want to think about it that way.”

Surgery on conjoined twins is rare, and such a procedure hadn’t been performed at MGH for more than 15 years. Still, Goldstein had been involved in complex surgeries before, and, after reviewing the available diagnostic imaging, he invited the family to fly to Boston.

“They were desperate — certainly eager — to do something to help their children,” he said.

Ethical ordeal

When the family first arrived at the hospital, doctors examined the twins, completed new imaging scans, and then began to think through whether and how the separation could be accomplished.

The girls had faced each other since birth, heads and shoulders separate but lower trunks fused. They shared a liver, bladder, and intestinal tract, their pelvises were intertwined, and they had three legs between them. Their conjoined circulatory systems were most worrisome of all.

Imaging showed that the larger and stronger twin, whose heart, lungs, and circulatory system were relatively normal, was supporting her weaker sister. The weaker twin’s heart had just three chambers instead of the normal four, and irregular blood vessels between the heart and lungs, a critical loop in which blood takes up oxygen and delivers it to the rest of the body.

The most crucial connection was between the stronger twin’s oversized superior mesenteric artery, which normally supplies blood to the intestine and pancreas, and the weaker twin’s abdominal aorta, the main pipeline that brings blood to the lower body.

Tests of the weaker twin’s blood-oxygen levels showed values near normal in her leg and lower body — likely due to her sister’s support — and reduced levels in her upper extremities, where she was more reliant on her own malformed heart and lungs. Doctors realized that if the connection between the girls was cut, the weaker twin’s circulatory system might give out.

They also realized that, given the conjoined circulatory systems, if the weaker twin were to die, her sister would also perish.

In this harrowing ethical territory, with surgery to save one girl almost certain to mean death for the other, Goldstein sought guidance from Brian Cummings, chair of Mass General Hospital for Children’s pediatric ethics committee, a physician in the hospital’s pediatric intensive care unit, and an assistant professor of pediatrics at HMS.

Cummings turned to medical literature, looking for guidance from past decisions, including accounts of a 1977 surgery by C. Everett Koop on twins who shared a heart, and a U.K. case in which courts determined that a separation surgery should proceed if it allowed at least one twin to live.

After review, Cummings and his fellow committee members advised that the surgery should move forward, with the parents’ consent. They also recommended that hospital personnel who objected to the procedure be allowed to step away, an option that several physicians exercised, asserting that doctors should not take actions leading to a child’s death, Goldstein said.

Separation, and goodbye

Within a few days of the initial meeting with doctors, the weaker twin had developed a respiratory infection that worsened into pneumonia. The illness reduced oxygen to her upper extremities enough that the beds of her fingernails turned blue. Admitted with her sister to intensive care, she received supplemental oxygen, antibiotics, intravenous fluids, and a nasogastric tube for food.

It took a week for the pneumonia-stricken twin to improve and 10 days before the girls could be discharged. Six days later, however, the infection recurred. The weaker twin arrived at the hospital with a temperature nearing 100 and blood-oxygen levels of just 32 percent.

“There was definitely a realization, from the ICU’s perspective … they actually might both die before we could get to an operation,” Cummings said.

The illness heightened the urgency of the situation. One sister was failing. The challenge of assembling and coordinating specialists — including nine surgeons and two anesthesiology teams — still remained. Having spoken to the parents, who made their decision after consulting with a religious leader, Cummings and Goldstein accelerated their plan.

The doctors opted to keep the girls in the hospital after the infection cleared, moving them from intensive care to a regular room, where they could be monitored to ensure they were healthy enough for surgery. The girls connected with their caretakers, Cummings said, singing songs and shaking maracas. They were affectionate with each other, the weaker twin draping her arm over her sister. They were also protective, one protesting and flailing her arms when staff tried to stick the other with needles.

The 14-hour operation involved roughly 50 people, including physicians, nurses, and technicians. It had been carefully choreographed, with one team of specialists taking over, doing its part, and giving way to the next.

Anesthesiologists calibrated the proper dose to sedate two children who shared a circulatory system. Plastic surgeons made the first incisions, heedful of how the bodies would be closed after the procedure. General surgeons separated organs, leaving intact the key artery the girls shared. Orthopedic surgeons worked to untangle the pelvis bones.

Then, stepping forward again, the general surgeons cut the mesenteric artery. The lifeline between the twins was gone.

“My 14-year-old daughter just asked me … ‘Did you violate the Hippocratic oath?’ … I said, ‘First, thank God you’re not a reporter. And second, it’s a great question and I don’t know the answer.’”

“I thought about this over and over,” Goldstein said. “We probably knew there was no hope and yet I just maintained hope the whole time. We had another operating room ready. We hoped she would live at least a little while — hours, days — so her parents would have a chance to say goodbye. Maybe if you asked me, purely on an intellectual level, I would have admitted there was no hope, but I didn’t want to think about it that way.”

But Goldstein and the other doctors had been right. With the girls finally separated, the weaker twin’s heart wasn’t up to the task and her blood pressure began to drop. She did not survive the operation.

“When she died, it was very, very difficult,” Goldstein said. “It’s definitely the only time I’ve cried in the operating room.”

After plastic surgeons closed openings in their bodies, the sisters were moved back to intensive care, one to start weeks of recovery, and the other so that her parents could say goodbye.

A hopeful reunion

Grand rounds have long been a tradition at Mass General. Unlike everyday rounds, in which a physician visits patients with medical students in tow, offering a firsthand look at treatment and care, grand rounds are less frequent and more lecture-like, a way for doctors to present unusual or important cases — details, outcomes, implications, and lessons — to students and colleagues.

In the spring of this year, Goldstein led grand rounds at a hospital amphitheater, enlisting the help of the ethicists, cardiologists, anesthesiologists, plastic surgeons, and others who had played key roles in separating the twins. It had been 13 months since the surgery and the family was in attendance.

The girl was doing well, Goldstein told his audience. Her bodily functions were relatively normal, and she was crawling on her own and standing with assistance. Several surgeries still lay ahead: to repair a malformed leg and foot so she could walk normally, to correct remaining abnormalities in her pelvis and abdominal organs. She nonetheless clapped, waved, and charmed the crowd packing the room.

“It was surgical grand rounds, which has probably been happening since the 1800s, and multiple people — some who have been there nearly that long — told me it was the best grand rounds they have ever been at,” Goldstein said. “Every time the crowd would clap, she would clap. We’d stop, she’d stop, and then we’d clap again.”

The parents are happy with the health and progress of their surviving daughter, Goldstein said. He still thinks often about the loss of her sister — in sadness, not agony. He doesn’t doubt the right decision was made.

“Step one was a willingness to hear a story,” Goldstein said. “This family had gone through so much. … It is what we do every day. Our primary goal is still to help people.”