Stephanie Pierce, Chris Capobianco, and Blake Dickson survey the Bay of Fundy at Blue Beach, Nova Scotia.

Photo by Katrina Jones

Retracing Romer’s footsteps

Mystery drives Nova Scotia fossil quest in tidal area where famed scientist once worked

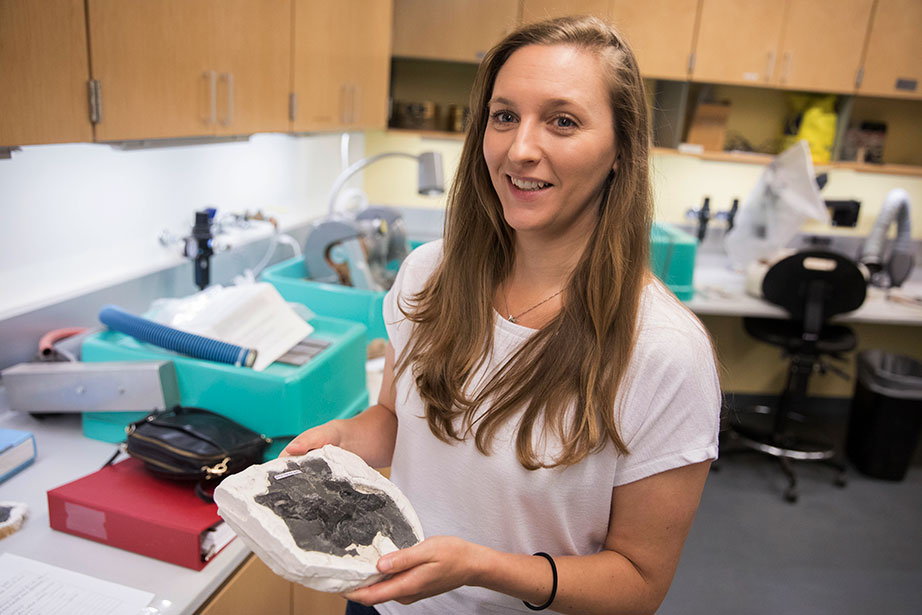

The mood was celebratory on a remote, rock-strewn beach in Cape Breton, Nova Scotia. Stephanie Pierce and her paleontology team had uncovered a fossilized jaw measuring more than a foot and were snapping selfies when they were struck by a question.

“Oh, my God, how are we going to get this out?” Pierce said, laughing.

Gap in the fossil record

The curator of vertebrate paleontology at Harvard’s Museum of Comparative Zoology and assistant professor in the Department of Organismic and Evolutionary Biology was in Nova Scotia after winning a Putnam Expedition Grant to walk in the footsteps of Alfred Romer, a Harvard paleontologist and biologist for much of the 20th century who specialized in vertebrate evolution.

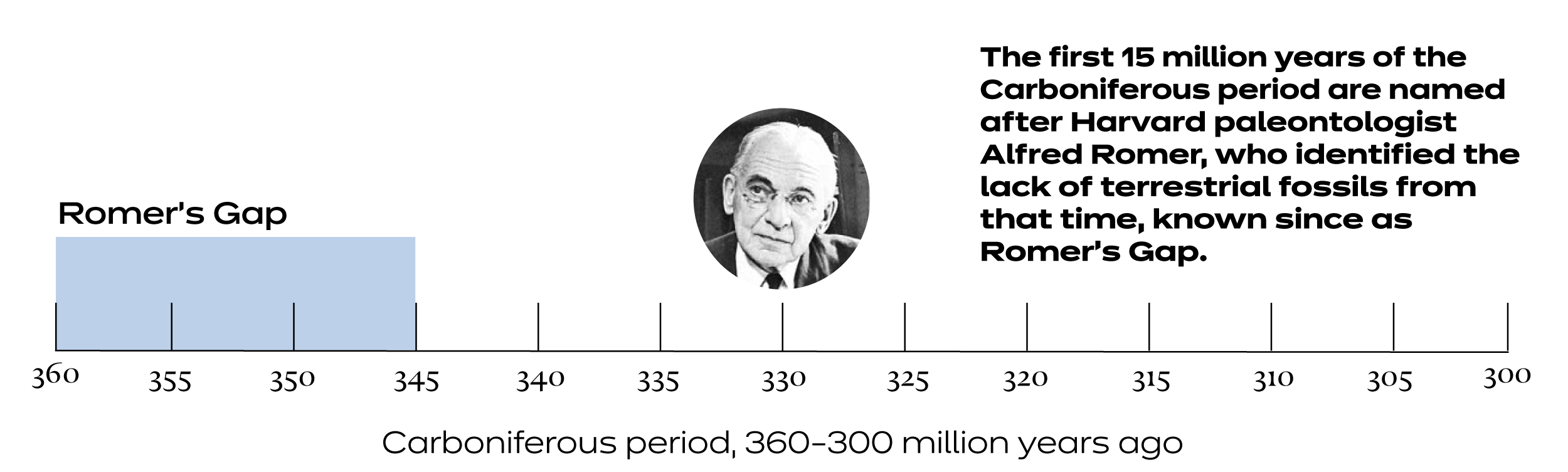

An entire era of the fossil record is named after Romer, who identified the unexplained scarcity in tetrapod fossils from the early Carboniferous Period, when animals first crawled out of the ocean and walked on four legs. “Romer’s gap” spans the period 360-345 million years ago, and to this day remains a mystery.

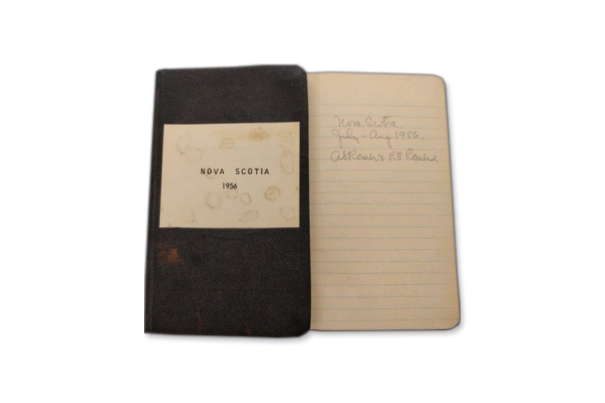

In the 1950s, Romer searched Nova Scotia for tetrapod fossils from the early part of the Carboniferous period, and his field notes, below, are archived at Harvard. Photo (below) courtesy of the Museum of Comparative Zoology

Graphic by Rebecca Coleman/Harvard staff

Clues in old field notes

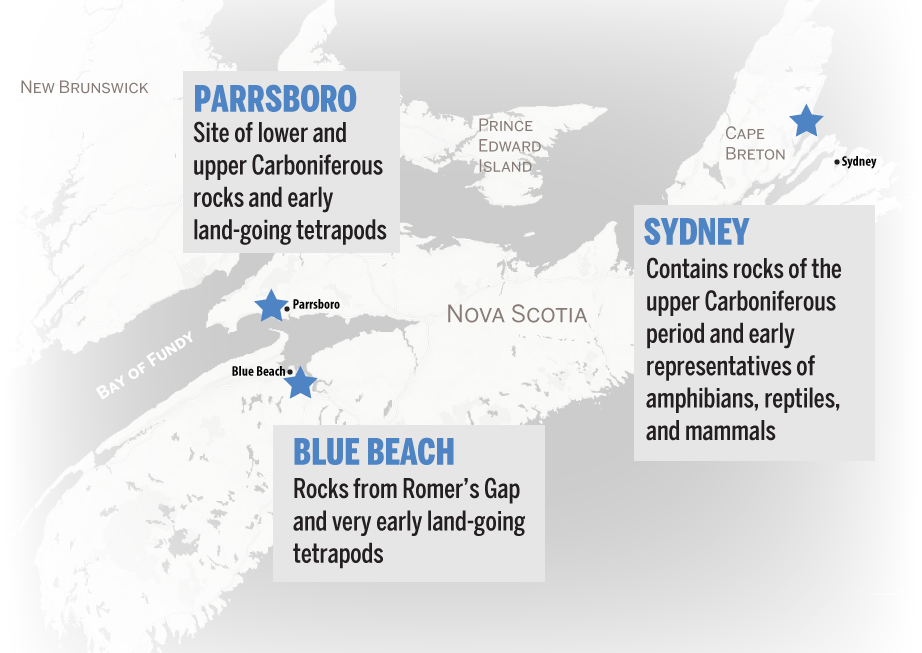

Guided by detailed field notes from Romer’s 1956 expedition combing Nova Scotia — the only site besides Scotland where terrestrial fossils from this period have been found — the group set out in June to retrace his steps and probe the area with fresh eyes. They hit three main areas: Parrsboro, Blue Beach, and Sydney.

Erosion from decades of waves crashing ashore had altered the topography, but some things hadn’t changed since 1956. Romer’s notes contained a business card from an inn where his team had stayed, so in the spirit of tradition, Pierce’s crew slept there, too. All members of the 2017 team also kept detailed field notes from their expedition, which will be archived alongside Romer’s at Harvard for future reference.

Blake Dickson and Chris Capobianco haul a giant boulder containing a tetrapod jaw across the beach.

Photo by Stephanie Pierce

When determining their route, the team consulted Alfred Romer’s field notes, geological maps, and Harvard databases and specimens. Source: Stephanie Pierce

Graphic by Rebecca Coleman/Harvard Staff

‘Racing against the tide’

The team moved quickly each day along the rugged coast Romer had studied.

“The tide goes out, and you have a window of about six hours before it comes back in,” Pierce said. “And it comes in fast! About 10 vertical feet every hour.”

When they found fossils, there was little time to waste before they had to haul the heavy rocks back to their base, “bruised and battered, racing against the tide” — the Bay of Fundy has the world’s highest, with waves cresting up to 50 feet.

Worth the weight

Pierce called the work both “exhilarating and frustrating.”

All the highs and lows of fossil hunting were in effect the day they trekked north to an uncharted site and tried to access a remote beach flanked by private property. They sought help from a friendly passerby, who, in a stroke of luck, happened to be the harbormaster. Soon she was sweeping them down an unmarked road in her vehicle to a largely unexplored stretch of beach.

Pierce remembers spotting “an unusual rock.”

“It didn’t even look like it would be a fossil,” she said. But it was. Then they found another one, and another. The jewel was a jaw from a large tetrapod.

“The rock didn’t seem to be the type to have fossils in it, but something on the surface made me reach for it and take a closer look,” Pierce said.

It took four people four hours to lug the fossils a little less than half a mile. But the slog was worth it.

“I think we found something new for Nova Scotia Carboniferous tetrapod evolution,” Pierce said.