Harvard Professor Emeritus Lawrence Buell reflects on the lasting importance of Henry David Thoreau’s “Walden” on the 200th anniversary of the author’s birth.

Video: Director and editor Joe Sherman; videographers Kai-Jae Wang and Catherine Seraphin/Harvard Staff

Thoreau at Walden, and at Houghton

Visiting naturalist’s inspirational site, Harvard professor reflects on the lasting import of his seminal text, and of his world view

Lawrence Buell was a teenager when he first read “Walden,” Henry David Thoreau’s homage to simple living and the wonders of nature. Buell was 17 and on the edge of manhood, challenging assumptions, questioning authority, and watching with dismay — as Thoreau did in his beloved Concord — as the modern world encroached on his home.

“I was a country boy growing up in a place west of Philadelphia that was becoming engulfed by suburbia,” said Buell during a visit to the famous pond and woods where Thoreau lived in a rough cabin for two years in the 1840s and where “Walden” took shape.

Standing in a small hillside clearing near the railroad tracks that still hum with trains, with a view through the trees of the famous kettle pond immortalized by the book that bears its name, Buell recalled how Thoreau’s personal narrative, his love of the landscape, and his trademark candor and wit struck a deep chord.

More like this

“Thoreau’s outspokenness appeals to the adolescent mind. It also appeals to anybody with an ounce of contrarianism,” said Buell, who loves Thoreau’s line: “Beware of all enterprises that require new clothes.”

Buell’s first encounter with Thoreau marked the beginning of a lifelong interest in the naturalist writer and in Transcendentalism, the philosophical and social movement that promoted “the notion of the god within, or the unlimited power of the individual.”

Harvard’s Powell M. Cabot Research Professor of American Literature Emeritus, Buell is the author of “The Environmental Imagination: Thoreau, Nature Writing, and the Formation of American Culture,” a study of how literature portrays the natural environment, and has been a pioneer in the field of ecocriticism. He taught Thoreau’s seminal text for years, both at Harvard and at Oberlin College in Ohio. The 200th anniversary of Thoreau’s birth is July 12.

Buell said new generations of students continue to connect to “Walden,” which was published in 1854, because of its myriad themes.

“It’s been described as an aesthetic product of great elegance and sophisticated craft. It’s been described as an early piece of conservationist writing. It’s been described as a how-to-do-it book for those who want to do start-ups — free enterprise. So there are lots of handles that you can grab ahold of, and that makes it fun to teach and read, and reread.”

The book also resonates so many years after its publication in large part because of its strong environmental message in the age of global warming, said Buell. The more the natural world is under siege, “the more the eloquent testimony by the protectors of the natural world … becomes relevant.”

In Buell’s eyes, Thoreau’s message of self-reliance also resonates with those today who feel powerless.

Thoreau’s classic “is a book about breaking away from life as usual, life as stultifying and enforced by the conformity of your social group. So the worse things get in these ways, the better it is for ‘Walden,’ that is, the percolation of the book.”

If there is one main takeaway from the famous treatise, it’s the notion that anyone can “kick-start their own renewal,” said Buell. “Thoreau kind of sums it up by saying if you advance resolutely in the direction of your dreams, you will meet with success unanticipated in your common hours.”

Thoreau at Houghton

On the second floor of Harvard’s Houghton Library, three small glass cases shine light on the intellectual giant.

On view through Sept. 2, “Henry David Thoreau at 200” coincides with his bicentennial and features a selection of the library’s holdings on him. The small exhibit is organized around the writings, political leanings, and lifelong friendships of the graduate of the Class of 1837.

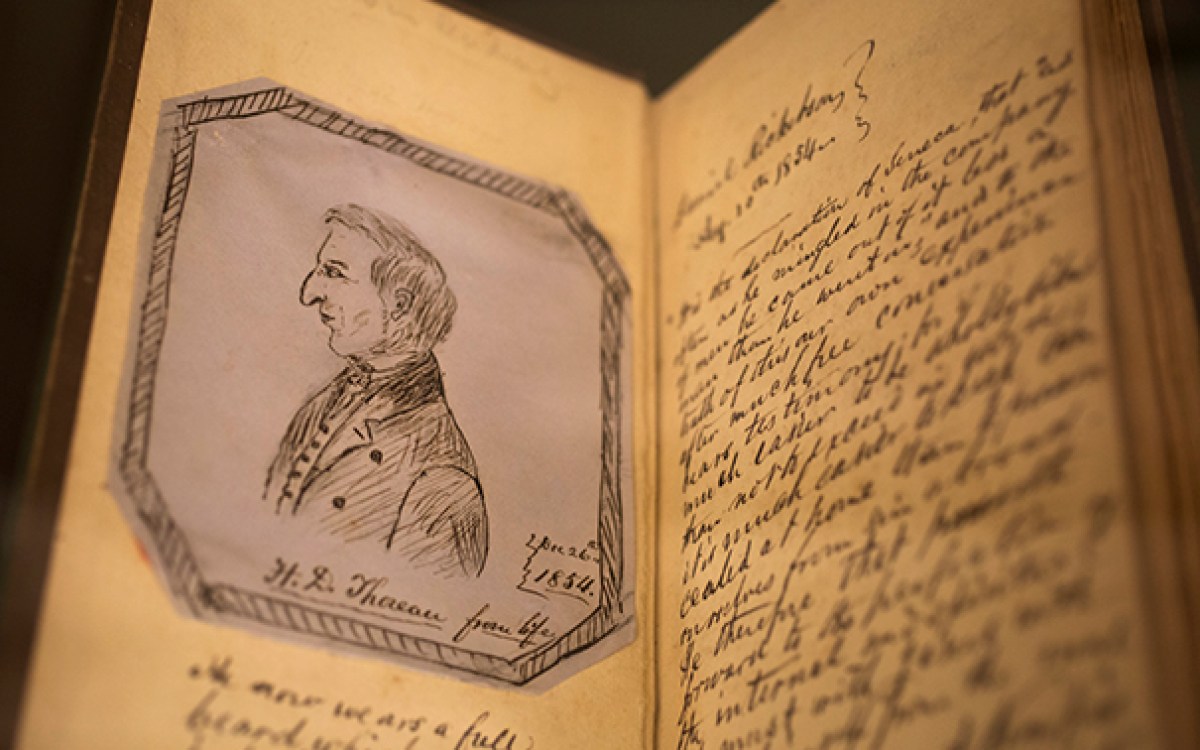

Early copies of “Walden” are part of the display, including one belonging to Thoreau’s friend Daniel Ricketson, who sketched quirky pictures of the author in its pages. Other items point to social and political elements of Thoreau’s writing, such as an autographed draft edition of his essay “Reform and the Reformers,” and a copy of his famous work “Resistance to Civil Government,” later titled “Civil Disobedience.”

According to Leslie Morris, Houghton’s curator of modern books and manuscripts, the library is fortunate to have these holdings. After his death in 1862, Thoreau’s sister sold most of his papers to a New York book dealer. Many of his journals were ultimately “cannibalized,” said Morris, sold off in pieces and bound into reprinted editions of his works to improve sales.

“We are so lucky to have so much, considering what happened to his papers,” said Morris.

The exhibit includes a “fact-book” from Thoreau’s later years, in which the author, who saw connecting with nature as a key to a meaningful existence, jotted quotations from contemporary naturalists and made observations about the world. Thoreau’s swooping script in black ink on the book’s blue pages recounts “an excursion to the white hills,” as well as “camping out many nights,” and a moose.

In one case devoted to the theme of friendship is an autographed, undated manuscript of a Thoreau poem titled “Friendship.” It also contains what staff consider the library’s most important Thoreau holding: nine pages of a manuscript recounting the author’s shoreline search for the body of his friend, the social reformer and author Margaret Fuller. Fuller drowned near New York’s Fire Island on July 19, 1850, after her ship ran aground in a storm. Thoreau was sent on the search mission by his friend and mentor Ralph Waldo Emerson.

“What I found so compelling when considering whether to purchase the notes is that it links together three people whose papers are at Houghton: Emerson, Thoreau, and Fuller,” said Morris.