SEAL-tested, NASA-approved

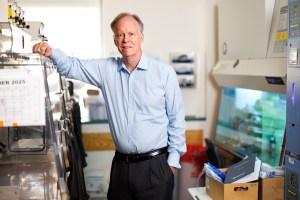

Harvard University Medical School graduate, Jonny Kim, an emergency medicine resident at Massachusetts General Hospital and former Navy SEAL, was named as part of NASA’s new astronaut class.. Rose Lincoln/Harvard Staff Photographer

Harvard Medical School grad to depart residency for astronaut training

Jonny Kim was in the grocery store when the call came: He would have to exchange his emergency room scrubs for a space suit.

“I was happy, jubilated, excited — all these emotions,” Kim said. “My wife was there. I told her and she was jumping up and down in the grocery store. So we looked silly. I was about to pay for the food.”

Kim, a 2016 Harvard Medical School (HMS) graduate, was one of a dozen candidates picked by NASA in June for its next astronaut class. A year into a four-year residency at Massachusetts General Hospital (MGH), Kim will put his medical career on hold so he can learn to fly a plane, spacewalk, operate the International Space Station’s robotic arm, and master other skills NASA considers essential.

This isn’t the first time Kim has exchanged one high-pressure career for another. Before going on inactive reserve to pursue his medical training, he was a Navy SEAL with more than 100 combat missions under his belt. His military honors include a Silver Star and a Bronze Star.

“Why wouldn’t NASA want him?” said David Brown, head of MGH’s Department of Emergency Medicine and MGH Trustees Professor of Emergency Medicine at HMS. “We wanted him. Harvard Medical School wanted him. Everyone wanted him.”

Kim, 33, has come a long way from the shyness and small dreams of his Los Angeles youth. Buffeted by family instability and a difficult time at school, he didn’t see in himself the qualities he admired in others: the courage of the astronauts whose posters adorned his walls, the quiet professionalism and odds-defying determination of the Special Forces. As high school graduation neared, it seemed only a radical step could get him off the road to nowhere. So he enlisted in the Navy and asked to become a member of one of its elite SEAL teams. The recruiter could promise only the chance to try. For Kim that was enough.

“I didn’t like the person I was growing up to become,” he said. “I needed to find myself and my identity. And for me, getting out of my comfort zone, getting away from the people I grew up with, and finding adventure, that was my odyssey, and it was the best decision I ever made.”

SEAL training was just as tough as advertised, Kim said. He considered quitting during “hell week,” a five-day stretch of near continuous training in cold, wet conditions.

“They let us sleep for a couple of hours in nice sleeping bags, one of only two naps you get in five days of training,” Kim said. “And when you’re snuggled up in this warm sleeping bag and they wake you up and immediately make you go in the frigid ocean, it was the closest I ever came to quitting. I had that taste of comfort, and then it was taken away from you. The cold was magnified because your body’s so broken. When you’re exercising, you can push through the pain. When you’re cold, you’re just by yourself.”

Once past the initial phase, Kim had additional training that prepared him for service as a navigator, sniper, point man, and combat medic. Combat was inevitably very different from what he envisioned as a high school recruit, and Kim said he still feels a duty to close friends killed in fighting.

“I don’t watch a lot of war films and documentaries anymore,” he said. “Losing a lot of good friends galvanized me and made a lot of my remaining teammates make sure we made our lives worthwhile. I still, to this day, every day, think of all the good people who didn’t get a chance to come home. I try to make up for the lives and positive [impact] they would have had if they were alive.”

Kim traces his interest in becoming a doctor to a day in 2006 in Ramadi, Iraq, when he was serving as a medic and two close friends were shot. Both eventually died. Kim treated one in the field.

“He had a pretty grave wound to the face,” Kim said. “It was one of the worst feelings of helplessness. There wasn’t much I could do, just make sure his bleeding wasn’t obstructing his airway, making sure he was positioned well. He needed a surgeon. He needed a physician and I did eventually get him to one, but … that feeling of helplessness was very profound for me.”

The doctors and nurses who worked on his friend made a lasting impression on Kim. Three years later, in 2009, having joined a Navy program through which enlisted personnel can be commissioned as officers, he left for undergraduate studies at the University of San Diego, with the intention of ultimately going to medical school.

He earned a bachelor’s degree in math in three years — the Navy required full course loads during the academic year plus summer school — and then, in 2012, arrived at Harvard Medical School.

Among the people he met early in his HMS career was Assistant Professor of Neurobiology David Cardozo, associate dean for basic graduate studies, who served in the Royal Canadian Navy and acts as an informal mentor for veterans on campus. The Medical School’s community of veterans is small, numbering about 20 at any one time. Students with special operations backgrounds are even fewer. Though Kim was one of the School’s most decorated veterans, Cardozo was struck by how modest he was.

“He’s the steadiest person you could imagine,” Cardozo said. “He’s very gifted and he has a depth of character that’s unequaled. He did wonderfully here.”

During his third year at HMS, Kim entered a mentoring program and met Brown, who heads the hospital’s Emergency Department. After graduating, Kim decided to specialize in emergency medicine and joined the Harvard Affiliated Emergency Medicine Residency, a cooperative program between MGH and Brigham and Women’s Hospital.

Kim wasn’t expecting to go to astronaut school — not yet, at least. He joined more than 18,000 other applicants for the NASA class — recruited every four years — as a first step, hoping to improve his chances in the next selection process, once his medical training was complete.

“So we were all surprised and thrilled when he was selected, but not really all that surprised,” Brown said. “He’s just a remarkable young man … incredibly committed, absolutely unafraid.”

Kim said he’s ready for whatever NASA asks. Due in Houston in late August, he recently left the residency program to prepare for the move with his wife and children.

“I’m going to be a student at the bottom of another totem pole trying to learn as much information as possible,” he said. “I’m excited for the adventure. I think it’ll be another occupation where I say, ‘I can’t believe I’m getting paid for doing this.’”