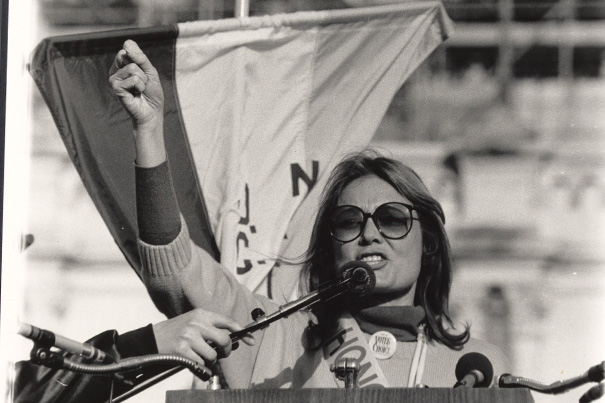

Students in a new class on feminism learned about leaders in the struggle for women’s rights, such as social activist Gloria Steinem who fought for decades for women’s reproductive rights.

Courtesy of Schlesinger Library/Radcliffe Institute, Harvard University; photo by Dori Jacobsen-Wenzel

Fresh thinking on history of feminism

Class, timeline explore lesser-known narratives in movement’s rise

For many, feminism just took a flying, sword-wielding leap with “Wonder Woman,” the new film in which Amazonian warrior-princess Diana of Themyscira serves as protector of the free world. The Patty Jenkins-directed movie, the first superhero feature with a woman in the leading role, grossed $223 million worldwide in its opening weekend, the third-biggest launch for a DC Comics movie.

Though an important milestone for some, others consider the film just one more step on the long, complicated road to gender equality, a road Harvard cultural historian Phyllis Thompson and her class of undergraduates explored during the spring term.

Thompson’s class “The History of Feminism: Narratives of Gender, Race and Rights,” a new Harvard offering that examined the evolution of major feminist narratives, aimed to replace the notion of a steady stream of progress with a more nuanced appreciation of the many actors, seen and unseen, responsible for advancing women’s rights over time.

“There have been extraordinary thinkers from many places and many intellectual orientations and a broad variety of racial backgrounds who have had extremely progressive ideas ahead of their time,” said Thompson, a lecturer in studies of women, gender, and sexuality. “And if we periodize the history of feminism strictly along a chronological basis it’s really easy to lose track of that.”

To help students dig into history and develop a more “honest appreciation for the past,” Thompson structured her course around four themes: the fight for political and economic citizenship; the regulation of family and domestic life; the struggle for the freedom of sexual expression and reproduction and identity politics; and the significance of utopian visions, idealism, and manifestos.

“My thinking was that each time the students would go through the history from a different approach they would be forced to wrestle with what they knew, what they didn’t know, what the real genealogy is for any particular person or action,” said Thompson.

Despite disrupting the “progress narrative,” the class put chronology at the center of one important assignment, a timeline designed to illuminate understudied facets of feminism. The online record created by students starts in the fourth century B.C. with Agnodice, the first Athenian female physician, and ends with Viola Davis, who became the first black actor to win an Oscar, Emmy, and Tony when she took home an Academy Award on Feb. 26 for her supporting turn in the film “Fences.”

There are other online timelines that chart feminism, but most begin sometime around 1700 and mainly support the idea of three important “waves.” The first, from the 19th century to the early 20th, stressed the vote, while the second, from the 1960s to the ’80s, emphasized equality in the workplace and in other areas of society. The third is ongoing, with a focus on cultural diversity.

But defining the movement in such a strict chronological sense ignores critical voices, Thompson said.

For example, she said, “that kind of periodization effaces the work that black feminists did in the 19th century because they are not involved in the fight for the vote in the same visible way as, say, [Elizabeth Cady] Stanton and [Susan B.] Anthony, and yet they are fundamentally more progressive.”

To address another imbalance, Thompson had her students contribute feminist-related entries to the largely male-oriented online encyclopedia Wikipedia.

“Around 90 percent of the Wiki authors are male, so there’s been a real short-shrifting of topics pertaining to women and to feminism,” said Thompson, whose students crafted submissions on topics ranging from the Project on the Status of the Education of Women to Vilma Rose Hunt, a scientist and Radcliffe College graduate who helped establish links between smoking and lung cancer.

Nora O’Neill ’18, a history of science concentrator with a secondary in women and gender studies, worked on a submission about the Junior League of Boston, a service-devoted women’s volunteer group founded in 1906. O’Neill said the course not only helped her understand how much of “history is political,” it also offered her a concrete way to make a difference.

“Much of our own history has been ignored and erased,” said O’Neill. “This class was a way for me to learn that history, but also to fight back, to force inclusion of female figures in our mainstream history, like through Wikipedia.”

Students also wrote about 70 entries for the Online Biographical Dictionary of the Woman Suffrage Movement in the United States, an archive compiling biographical sketches of female supporters of suffrage campaigns in the first two decades of the 20th century.

For much of their research, students needed only to take a quick walk across campus. Librarians at the Arthur and Elizabeth Schlesinger Library on the History of Women in America at the Radcliffe Institute for Advanced Study provided key support. Thompson said about 20 percent of the timeline’s entries came from Schlesinger material.

In addition to encouraging students to “be makers of public history — to make feminism” through research and writing, Thompson urged them to make the future. For final projects, students crafted their own visions for a more equitable world in the form of a manifesto, a work of art, or a film.

Several men took the class, including Jake Stepansky ’17, a psychology concentrator with a secondary in Theater, Dance & Media. Along with feeling like he was making “real-life contributions” through the various assignments, Stepansky said the classroom discussions helped him understand he was “coming from a place of privilege as a white male.”

“If you are really trying to be diverse and inclusive,” he said, “it’s important to go into rooms with people who aren’t like you and just listen.”