The balance in healthy aging

To grow old well requires minimizing accidents, such as falling, as well as ailments

Fourth in an occasional series on how Harvard researchers are tackling the problematic issues of aging.

The morning light is pouring into the senior living community in Canton, where six residents are performing an exquisite choreography of sweeping, lyrical movements, emulating their Tai chi instructor.

“Wave hands like clouds,” urges Kerry Paulhus, leading them in the classic low-impact and slow-motion exercises of the ancient Chinese martial art. With relaxing music playing in the background, the students shift their weight from one leg to the other, turn their waists, and rotate their arms as if they indeed were clouds.

When class ended, Elaine Seidenberg and Fran Rogovin, both 84 and close friends for four years, were glowing.

“Tai chi calms me down and has lowered my blood pressure,” said Rogovin at Orchard Cove, a facility that is part of Hebrew SeniorLife. “It’s just amazing what Tai chi has done for me.”

“In class, we wave hands like clouds,” agreed Seidenberg, a former Cape Cod resident. “And after class, we walk on clouds.”

While Tai chi may offer senior practitioners inner peace, scientists also value it for its fundamental, physical benefits. In addition to improving balance, flexibility, and mental agility, it also reduces falls, the largest preventable cause of death and injury among older adults. One way to help the aging have long and vital lives, researchers say, is to help protect them from injuries or worse.

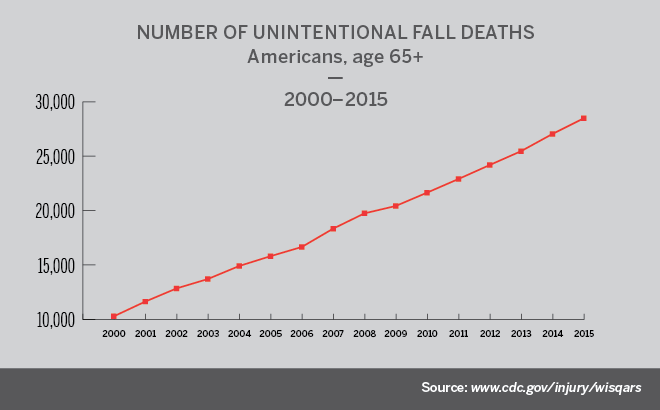

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, one in three older adults falls dangerously each year. In 2014, about 27,000 older adults died from falls, more than 2.8 million were treated in emergency rooms, and 800,000 were hospitalized. Falls are the leading cause of death among adults over 65, and the death rate from them has soared in the past decade.

Over more than 30 years, researchers at the Institute for Aging Research have been studying what causes these falls among the elderly, and how to prevent them. The institute was started at Hebrew SeniorLife 50 years ago to take advantage of the proximity to senior residents living nearby, said Lew Lipsitz, institute director and chief academic officer.

Hebrew SeniorLife, a senior health care and housing organization affiliated with Harvard Medical School (HMS), serves 3,000 seniors in nine residential communities throughout Boston. One of a kind, the Harvard affiliate is the only long-term chronic care teaching hospital in the United States. The resulting access by researchers to seniors and their everyday lives provides a major boost to the real-time value of their research.

“Researchers really enjoy working here,” said Lipsitz, who is also chief of the Gerontology Division at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center and professor of medicine at HMS, “because in fact it is an environment where researchers can identify the problems they want to study and apply studies to solve those problems.”

When Lipsitz began working at the institute in 1980 as one of the first Harvard fellows in geriatric medicine, he noticed that many residents fell frequently. His area of research was born.

Lipsitz directs the institute’s Center for Translational Research in Mobility and Falls. The center has led a number of groundbreaking studies on reducing the risk of falls among older adults, ranging from the benefits of Tai chi, to the role of high blood pressure in falls, to the use of electrical stimulation to the brain to aid executive functions, to the benefit of vitamin D to increase bone density.

Many of these studies over time were funded by the National Institute on Aging of the U.S. Department of Health & Human Services, and the National Institutes of Health.

Lipsitz calls tai chi one of the most “exciting” interventions because it benefits both balance and mobility. It aids the muscular system, coordination, equilibrium, and the brain. In 2010, researchers at the institute ran a 12-week intervention, in which seniors practiced Tai chi twice a week. At the end of the trial, the investigators compared balance and mobility of those who did Tai chi to seniors who just sat in on the classes. “And lo and behold, Tai chi not only their improved gait and balance but improved their overall functional ability,” said Lipsitz. “If we could put Tai chi in a pill, everybody would take it. But unfortunately you actually have to practice it to have an effect.”

A study by Lipsitz, Brad Manor, and other researchers concluded that Tai chi training “may be a safe and effective therapy to help improve physical function.” The Arthritis Foundation now recommends Tai chi because it reduces stress and arthritis pain. (A study led by Fuzhong Li of the Oregon Research Institute, which examined results of a Tai chi program offered in 36 senior centers in 4 Oregon counties between 2012 and 2016, showed a 49 percent reduction in the number of falls and improved physical performance.)

It’s a simple fact that balance — the ability to maintain the body’s center of mass, located in the chest area, over the base of support or the feet — declines with age. Maintaining and bolstering it requires more than strong bones and firm muscles.

“Social stimulation is an important part of our health, and this tends to decrease with aging. The social aspect of Tai chi becomes incredibly powerful, which helps with the enjoyment.”

— Brad Manor

“It’s not just a physical task; it’s also a mental task,” said Manor, director of the institute’s mobility and brain function lab, and an HMS assistant professor of medicine.

“We have to use our memory for the information that tells us how to perform the task of walking,” said Manor, “and we have to make decisions to slow down if there’s an icy road or the lighting is poor. So we need to use our attention, memory, and decision-making, which are all cognitive functions. It’s a very complex system that involves processes that take place in the brain.”

Because Tai chi requires attention, memory, and learning components to master its physical movements, its benefits go beyond improving mobility and reducing falls, the researchers say. It increases cognitive and mental functions and mindfulness. It also promotes social interaction because Tai chi is often practiced in a group setting.

“Social stimulation is an important part of our health, and this tends to decrease with aging,” said Manor. “The social aspect of Tai chi becomes incredibly powerful, which helps with the enjoyment. People really like it. It doesn’t really matter if you have a new intervention that may be more effective if people don’t enjoy doing it.”

In his lab, Manor studies the links between brain function and balance and falls. As part of his research, he monitors movements of participants while they walk and perform other mentally aware tasks such as counting backwards by threes, in what he calls a “dual-task assessment.” Often, falls among older adults happen when they’re walking while performing other tasks, because they get distracted and lose their balance.

“Walking is a cognitive task, and if we’re doing another cognitive task, like talking, one of the tasks will be diminished,” said Manor. “We’re studying how dual tasking interferes with losing balance. In one of the studies, we were able to demonstrate that people who did Tai chi improved their ability to walk and perform an additional cognitive task.”

Balance also depends on the ability to have feeling in the feet, which decreases as people age. Scientists at the institute partnered with the Wyss Institute for Biologically Inspired Engineering at Harvard to develop a vibratory shoe insole, a device that sends tiny signals to people’s feet, which a study led by Lipsitz showed improved gait and balance. “It’s not available to the public,” Lipsitz said, “but this is a promising area of research.”

Institute scientists are also studying the effects of electrical stimulation to the brain region that control mobility, balance, and dual tasking. “It’s like taking a small battery and applying it to your forehead,” said Lipsitz. “Someday, I’ll be sitting at the desk feeling tired, perhaps after a meal, and all I’d have to do is attach a ‘battery’ to my forehead to get a boost.”

Even as research continues, falls remain a major, rising worry. In 2015, the financial toll from falls among older adults amounted to $31 billion, and the costs are expected to increase as life expectancy grows. In 2014, the population of U.S. seniors was 46 million, and by 2030 more than 20 percent of the country’s population is projected to be 65 and older. Beyond the financial costs, falls can dramatically undercut seniors’ lives in ways ranging to dependence, depression, isolation, and loneliness.

As for Rogovin and Seidenberg, neither has fallen since she began practicing Tai chi, three and two years ago, respectively. Both live an active life at Orchard Cove. While they also practice yoga and meditation, they rave about how Tai chi has enriched their lives.

“It keeps me mindful of what I’m doing,” said Rogovin, who taught students with learning disabilities in Newton and Brookline for 30 years. “It relaxes me and helps my thinking.”

Seidenberg agreed. She especially cherishes the positive effects on her mental wellbeing. Tai chi not only helps her cope with the stress of dealing with her husband’s Alzheimer’s disease, but it makes her feel better.

“When I come out, I feel at peace with myself and the world,” she said. “Somehow when we age, we become less coordinated and a bit more clumsy, but I feel more graceful.”