Capgras syndrome is a rare disorder in which patients recognize a family member but experience that person as unfamiliar, leading to the conclusion that an impostor is impersonating their loved one.

Photo by Josh Rose/StockSnap.io

Love interrupted

Researchers probe what’s behind delusional misidentification syndromes

Neuroscientists at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center (BIDMC) have mapped the brain injuries — or lesions — that result in delusional misidentification syndromes, rare disorders that leave patients convinced people and places aren’t really as they seem.

In a study published in the journal Brain, a team led by Beth Israel neurologist and Harvard Medical School Associate Professor Michael D. Fox reveals the neuroanatomy underlying these syndromes for the first time.

“How the brain generates complex symptoms like this has long been a mystery,” said Fox, director of the Laboratory for Brain Network Imaging and Modulation and associate director of the Berenson-Allen Center for Noninvasive Brain Stimulation.

“We showed how complex symptoms can emerge based on brain connectivity. With a lesion in exactly the right place, you can disrupt the brain’s familiarity detector and reality monitor simultaneously, resulting in bizarre delusions. Understanding where these symptoms come from is an important step toward treating them.”

Delusional misidentification syndromes are among the most striking and least understood disorders encountered in neurology and psychiatry. First documented nearly a century ago, Capgras syndrome is a rare disorder in which patients recognize a family member but experience that person as unfamiliar, leading to the conclusion that an impostor is impersonating their loved one. Conversely, the Fregoli delusion is the belief that strangers are actually loved ones in disguise. Misidentification delusions can also apply to pets and places.

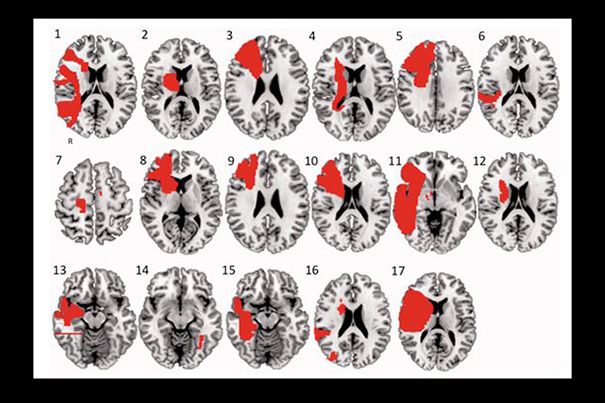

Fox and colleagues, including lead author R. Ryan Darby, the Sidney R. Baer Jr. Foundational Fellow in the Clinical Neurosciences at the Berenson-Allen Center, identified 17 patients with delusional misidentification syndromes and mapped them onto a standardized brain atlas. Then, using the lesion network mapping technique they had recently developed, Darby and colleagues determined that all 17 lesions were functionally connected to an area of the brain called the retrosplenial cortex, which is thought to be involved in perceiving familiarity. Sixteen of the 17 lesions were also connected to a region in the right ventral frontal cortex, which is associated with belief evaluation. The scientists compared the data to 15 control brain injuries that led to delusions other than misidentification delusions.

“Lesions causing all types of delusions were connected to belief violation regions, suggesting that these regions are involved in monitoring for delusional beliefs in general,” Darby said. “However, only lesions causing delusional misidentifications were connected to familiarity regions, explaining the specific bizarre content — abnormal feelings of familiarity — in these delusions. In other words, lesions had to be connected to both regions to develop delusions like Capgras.”

The scientists noted that their network mapping technique does not involve functional neuroimaging (fMRI). Rather, data from normal patients determine which regions of the brain are normally connected to the mapped lesion locations. While this methodology carries several advantages, it does not prove these two regions are dysfunctional in delusional patients following the lesion. Doing so would require recruiting a large number of patients with the rare disorder to a follow-up study, noted Darby.

However, the new information gleaned from the research may help patients’ families cope with a loved one’s misidentification delusions — which can disappear as mysteriously as they emerged.

“The impact on the patient’s family can be heartbreaking,” said Darby. “I’ve seen patients who, thinking their homes were replicas, would pack their bags every night, hoping to return to their ‘real’ home. Patients who believe a spouse is an impostor often lose intimacy. In these cases, even just knowing that the delusion has a name and is part of a neurological disorder can be helpful for family members.”

Co-authors included Simon Laganiere and Alvaro Pascual-Leone of the Berenson-Allen Center for Noninvasive Brain Stimulation, and Sashank Prasad of the Department of Neurology at Brigham and Women’s Hospital.