What do we know about suicide? Not nearly enough

Citing scant progress in efforts to predict self-harm, research calls for break with convention

Despite decades of research aimed at understanding the factors that might drive someone to attempt suicide, the sad fact is that scientists are no better at predicting self-harm than they were a half-century ago.

More like this

That’s the conclusion of a new paper that examined 365 studies of suicide risk factors over the past 50 years. The review, described in the Psychological Bulletin of the American Psychological Association, found that even the most modern studies predicted suicidal behavior only slightly better than random chance.

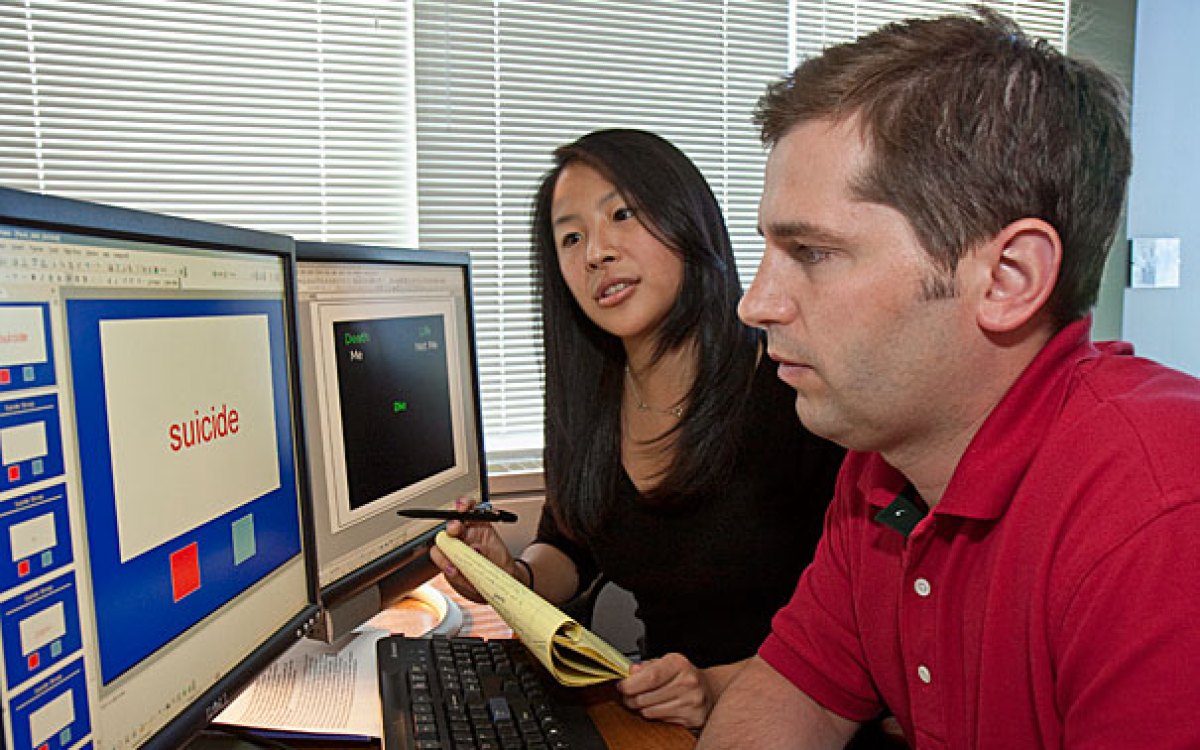

The solution, says senior author Matthew Nock, a Harvard psychology professor, may lie in taking a new approach to studying suicide by bundling multiple risk factors, much in the same way researchers consider factors like diet, exercise, and family history when evaluating heart disease risk.

Nock and colleagues argue that suicide researchers have for too long focused on the same risk factors in isolation. These include mental disorders such as depression and anxiety, substance abuse, socio-demographics, negative life events, and prior suicidal thoughts or behavior.

Co-authors on the paper include Joseph Franklin, a former postdoctoral fellow in the Nock lab who is now a faculty member at Vanderbilt University, as well as researchers from Boston University and Columbia University.

“Most studies have looked at one factor at a time, like what’s the effect of depression on suicide, or what’s the effect of alcohol or substance abuse on suicide,” Nock said. “The problem is that, as a field, we haven’t done a good enough job testing the effects of combining multiple factors together. We’re using the same predictors, but we’re not getting any better.”

One new approach, described by Nock and colleagues as “risk algorithms,” has shown some early promise in predicting suicidal behavior.

“In one recent paper we developed a machine-learning algorithm that combs through medical records and weighed each code as increasing or decreasing your risk,” Nock said. “By evaluating thousands of risk factors, we were able to predict about 40 percent of suicide attempts, on average, about three to four years before they occurred.”

While those results suggest a dramatic improvement over more traditional studies of suicidal behavior, Nock emphasized that such algorithms need more refining before they can be deployed in a clinical setting.

“Right now, we can use what we have to point clinicians toward people who might be at risk,” he said. “But to have something that’s really actionable, we need to be much more accurate.”

For the new research, Nock and colleagues evaluated hundreds of papers that had taken a conventional approach to understanding suicidal behavior by recruiting large groups of participants and following them for years to identify which factors played the largest role in self-harm. Because nearly all of the studies, from the 1960s to the 2000s, relied on the same handful of risk factors, it was not surprising that most came to similar conclusions, Nock said.

If that approach hasn’t worked, why, then, have researchers been so slow to try others? Lack of support is one barrier.

“I think a big limiting factor is the stigma around the topic of suicide,” Nock said. “We haven’t prioritized it as a society … and that’s preventing a huge amount of research on suicide.”

In the United States alone, suicide accounts for more than twice as many deaths as homicide, and more than five times as many deaths as HIV-AIDS. Yet despite such harrowing statistics, the federal government annually devotes more research dollars to studying headaches than suicide, said Nock. The new paper serves as a sobering message on the need for creative thinking around the problem, he added.

“We need new theories and new tests of theories that take a number of factors into account at once,” Nock said. “We also need better short-term studies so we can understand how these awful behaviors unfold. If you look at other causes of death, like heart disease or HIV, as we’ve invested in those problems … death rates have dropped enormously. But for suicide, the rate 100 years ago is virtually identical to the rate today. Hopefully, this kind of work can get us to focus more on this problem and help us to start to really make progress.”