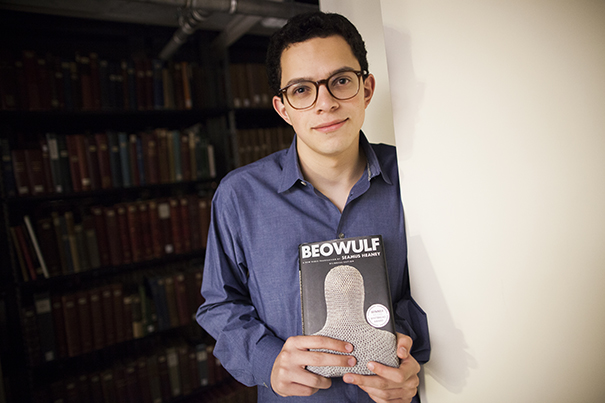

Charles Hyman ’18 is an English and history double concentrator on track to become a scholar of the Old English classic “Beowulf,” his obsession since childhood.

Stephanie Mitchell/Harvard Staff Photographer

A monstrous passion

In ‘Beowulf’ and other dead-language texts, junior finds enduring inspiration

This article is part of a series on the impact of humanities studies in and out of the classroom.

Through dead languages, Charles Hyman ’18 has found intellectual life.

In his deep study of Latin, ancient Greek, and now Old English, the 20-year-old history and English concentrator has discovered words that, far from being obsolete, are gateways to gripping narratives and powerful learning.

“They capture the imagination,” said Hyman, who recalled his earliest romance with ancient history, discovered while visiting reliefs of Assyrian hunters in the British Museum in London when he was 6. “It might seem unreachable. Yet if you learn these languages, you feel so connected with the past in an immersive way.”

At the heart of his affection for these extinct languages is an undying love of “Beowulf,” the eighth-century Old English epic he began listening to at age 10, as a book on tape, with his dad, Steven, a professor of stem cell and regenerative biology.

“At the beginning, I loved the blood and gore,” he said. “When you’re 10, it’s quite appealing and, admittedly, at 20 it still is.”

Sipping coffee at Lamont Café, Hyman recalled the monster Grendel’s arrival at the mead hall, one of many passages he’s memorized from Seamus Heaney’s translation of “Beowulf.”

Nor did the creature keep him waiting / but struck suddenly and started in; he grabbed and mauled a man on his bench, / bit into his bone-lappings, bolted down his blood / and gorged on him in lumps, leaving the body / utterly lifeless, eaten up / hand and foot.

[gz_soundcloud title=”” track_id=”287194955″ playlists=””]Student Charles Hyman reads from Seamus Heaney’s translation of “Beowulf.” [/gz_soundcloud]

It’s a moment — one of many — that makes the epic hard to put down. As an eighth-grader at Roxbury Latin, in West Roxbury, a teacher told Hyman to stop bringing it to class.

“So I brought “The Iliad,’” he said. “My teacher still wasn’t happy. He wanted literature from the 20th century.”

The Winthrop House resident noted that his parents have always convened “academically rigorous” dinner table conversation. The same is true for evening walks with his dad and the family collie, Flag.

“We get into passionate arguments and discussions that have molded me,” he said.

There have been many other formative exchanges. Hyman, an avid sports fan, remembered meeting Wole Soyinka, winner of the 1986 Nobel Prize in literature, at a Christmas party.

“I was 14 and he didn’t have a baseball card so naturally I didn’t recognize him,” he said. “When I introduced myself, I asked him who he was reading currently and he said Seamus Heaney. I started to get into a discussion with him about ‘Beowulf’ — the poetry of it — and it instilled me with drive. As soon as Derek Jeter stopped being the model for my existence, it gave me an idea of what I wanted to do.”

As a Harvard student, that’s meant immersing himself in courses like English Department Chair James Simpson’s “Arrivals: British Literature 700-1700,” taken last year. Part of the fun was writing an essay on his beloved “Beowulf.”

“I made the argument that though it was written from a Christian perspective, and its author clearly loathed paganism, ‘Beowulf’ had nostalgia for pagans or, more accurately, warrior pagan culture. I tried to be interdisciplinary, using linguistics, English, and history,” he said, before breaking into another passage from the poem.

Sometimes at pagan shrines they vowed / offerings to idols, swore oaths / that the killer of souls might come to their aid / and save the people. That was their way, / their heathenish hope; deep in their hearts / they remembered hell.

[gz_soundcloud title=”” track_id=”287194959″ playlists=”” height=””]Student Charles Hyman reads from Seamus Heaney’s translation of “Beowulf.” [/gz_soundcloud]

Simpson, Donald P. and Katherine B. Loker Professor of English, said he immediately recognized Hyman as “serious and very well informed” when, three classes into the course, he questioned his teacher’s understanding of “The Odyssey.”

“By the time he presented his essay on ‘Beowulf,’ mid-term, I understood that he was the kind of student who would profit enormously from learning to read Anglo-Saxon,” Simpson wrote in an email.

Hyman, a Newton native, is just as much a student of the past when he’s off campus. An avid gardener, he grows chives from the same seeds his grandmother used. His detailed study of his family’s genealogy has connected him to ancestors who survived the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory fire in New York City, died during the Holocaust, fought alongside Lajos Kossuth in Hungary, and served as court Jews during the Holy Roman Empire.

“These are disparate threads, but they do connect who I am,” he said. “It’s not just about family or history or literature. It’s about creating a worldview that combines these elements into what I hope is an empathetic and dynamic understanding of the world and my place in it.”