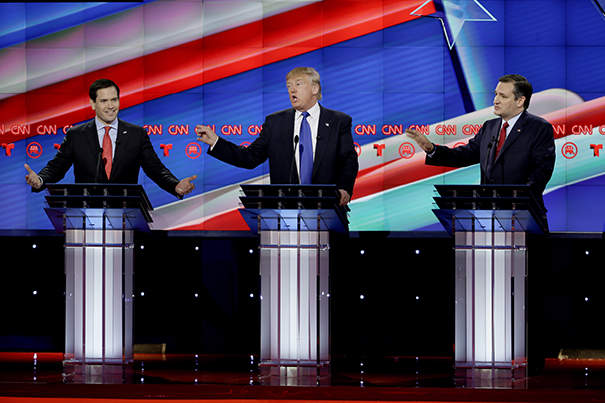

Republican presidential candidates Marco Rubio, Donald Trump, and Ted Cruz are pictured during the most recent GOP debate.

AP Photo/David J. Phillip

In GOP race, rage is all the rage

Discontent behind Trump’s rise has deep roots, analysts say

American politics is having a Howard Beale moment.

The fictional anchorman in the 1976 movie “Network” who famously rails “I’m as mad as hell and I’m not going to take this anymore!” — to the perverse delight of his ratings-obsessed producers — embodies both the tone and the tactics of the 2016 presidential election thus far.

Widespread voter anger at the perceived failures of lawmakers has driven the unexpected resonance of populist messages spread by Democratic Sen. Bernie Sanders and Donald Trump, the celebrity business mogul who holds a commanding lead in the fast-dwindling Republican field.

Deep hostilities vented at President Obama, immigration reform, America’s foreign policy, Muslims, the media, and marriage equality — along with a blanket rejection of anything that smells of politics-as-usual — have been the norm for GOP candidates vying to convince voters they’re tougher and smarter than their opponents.

Perhaps most surprising to observers is that Trump, a former Democrat, has vaulted to prominence despite lacking both political experience and conservative credentials. In fact, his popularity has relied largely on torching the tried-and-true playbook and targeting sacred cows of the GOP establishment, including free trade. Most recently, Trump’s refusal to immediately condemn support from white supremacists has intensified efforts by party leaders and more moderate Republicans to halt his bid for the White House.

It’s a bewildering civil war that many analysts say threatens to derail the party’s quest to retake the White House and could leave permanent damage in the process.

“What’s been remarkable all the way along is that the candidates with the least experience and the most anti-establishment positions are the ones doing the best on the Republican side,” said David Gergen, who served as an adviser to four presidents and is now a senior political analyst for CNN. It’s a dangerous dynamic that “could shatter the Republican Party in the long term.”

“I think there are conservatives and Republicans who know in their bones that the party is going off the rails. You hear [Gov.] John Kasich talk about that quite explicitly,” said E.J. Dionne Jr. ’73, an opinion writer for The Washington Post.

“I think a lot of Republican politicians were eager to use the discontent that the Tea Party and other forces on the right represented, but then found themselves cornered by that very discontent,” he said.

E.J. Dionne Jr.: American Conservatism and the Republican Party

Goldwater’s ghost

Although the party’s ideological fissure appears fresh, its history runs deep.

“There’s always been a more progressive, moderate wing of the party and there’s been a more conservative one and they frequently clash,” said Gergen, who traces the current party rift to the chaotic 1912 race between Woodrow Wilson; Theodore Roosevelt, Class of 1880, who represented the Eastern establishment; and the more conservative William Howard Taft.

But Dionne points to Barry Goldwater’s bitterly fought 1964 nomination as a comparably divisive race for the GOP that “set in motion the takeover of the Republican Party by its conservative wing.”

In a new book, “Why the Right Went Wrong,” Dionne argues that the Goldwater primary battle purged liberals and moderates from the party, and prompted defections by some Republicans. It was then that the power base began its shift from the Northeast and Midwest to the South, further alienating many Northern, Midwestern, and West Coast moderates who eventually abandoned the GOP, creating a party less inclined to compromise.

“So that when you look at who votes in Republican primaries now, it is a far more conservative group than voted in Republican primaries, say, in 1998 or 1992,” he said.

Besides anxiety over the direction of the country, an acute resentment and distrust of GOP leadership is at work, said Douglas Heye, a fall 2015 fellow at the Kennedy School’s Institute of Politics who has held top communications posts inside the Republican National Committee and the U.S. House of Representatives.

“I hear a lot that ‘We were promised that if only we took back the Senate, too, then we can do whatever we want to do.’ I don’t think a lot of people ever said that. The other thing I hear a lot is, ‘I want people who are going to fight!’” he said.

“I think there’s an outsized expectation about what can actually be done and therefore, there’s a pitting of ‘I’m fighting and you’re not,’ when the reality is all of our members are fighting pretty hard.”

“This is not an election so far about issues, this is an election about personalities,” said Gergen, who co-directs the Center for Public Leadership at Harvard Kennedy School (HKS). People see Trump as a turnaround CEO who “will finally turn this system around and make it work for working people.”

The public backlash against time-honored political rules is an “indictment” of not just elected officials in Washington, but of those in power in broader political circles and the media.

“We all ought to realize there’s a lot of anger out there and people feel they need to be heard and if we’re going to put this country back together, we’re going to have to listen to everybody, not just the voices of the commentariat, of which I’m a part, or the voices of the elites,” said Gergen.

There’s blame all over the map for the party’s crisis, said Heye. “I think our leadership can listen to our members better; I think our members can have more realistic expectations of what can be done.”

“If the Trump phenomenon dies … the party still has to figure out what do we do to appeal to those people who feel they’ve been completely left behind by the American political structure.”

Calamity with a silver lining

As the candidates head into the delegate bonanza known as Super Tuesday, Trump appears poised to win a majority of the 12 states in play. A broad and decisive victory could inflict near-fatal damage to the hopes of his closest rivals, Senators Ted Cruz, J.D. ’95, and Marco Rubio, and pave the way for Trump’s nomination.

“I don’t fear a Cruz nomination, [but] I think a Trump nomination would be an absolute calamity for the Republican Party,” said Heye, one that would cause the GOP to lose Senate and House seats along with state-level power, and would “absolutely” drive Democrats and others to the polls just to vote against Trump.

Though there has been some talk that party leaders might try to head off a Trump nomination at the convention, Gergen said “nobody knows” what will happen.

“Historically, the cliché has been on nominations that ‘Republicans fall in line and Democrats fall in love,’” he said. “Usually the Republicans line up behind whoever the candidate is and I would imagine you’ll see a lot of that.”

“The hope of moderate Republicans is if the party were to lose badly, that that would cause a major reassessment,” said Gergen. “There will still be factional fighting, but if you talk to Republican strategists, by and large, they will tell you, ‘If we lose this, the silver lining could be that it will give us a chance to put ourselves back together.’”

Election for the ages

Whoever wins, analysts see a historic election that’s likely to be studied for years to come.

“What we’re going to talk about is the end of mainstream politics as we knew it,” said Steve Jarding, a lecturer in public policy at HKS and an expert on campaign management. “It’s the advent of big money; it’s the advent of traditional institutions falling by the wayside; it’s the advent of media not playing its needed role.”

It’s also the first cycle in which the campaign-finance sea change ushered in by the Supreme Court’s ruling in Citizens United is in full bloom, he said.

“However the Republican Party reshapes itself after this election, whether they win or lose — and, to an extent, I think the same with the Democrats — this election has changed the way we do presidential politics,” said Jarding. “Unless we get money out of the equation, I don’t see how you go back.”

Dionne said he hopes the 2016 election represents the low-water mark in presidential politics and that the country will return to a more reasonable electoral process.

“The other thing that upsets me most is that the United States has some real problems right now, particularly the problem of an awful lot of blue-collar and middle-class Americans in this new economy: They are really hurting. Both parties need to take a warning from Trump that attention has to be paid to these voters and there are a lot of Americans who deserve a better shake than they’re getting.”

The flip side is that the country is in “remarkably good shape” compared with other countries coming out of the 2008 recession, said Dionne. “We can solve these problems and the only thing that might get in our way is political dysfunction and that is really disconcerting.

“I do think the answer to Trump’s ‘Make America Great Again’ hat is ‘America is Still Great.’ We have work to do and we need a political system that can get some of the work done.”