Lorraine O’Grady’s “The First and the Last of the Modernists Diptych 1 Red (Charles and Michael).”

Images (1, 3) by Lorraine O’Grady/courtesy of Alexander Gray Associates, New York; photo (2) by Elia Alba ©

At 81, her first solo show at home

Lorraine O’Grady, who thrives on juxtapositions, explains her art and influences

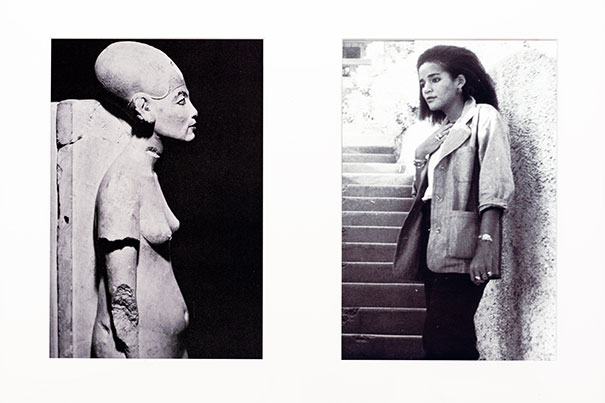

Just a year ago, the Harvard Art Museums reopened, uniting works from three museums under one roof. One of the inaugural exhibition’s most alluring discoveries awaited visitors in the Egypt Room. Among the ancient objects were two paired photographs of a young African-American woman and of Egyptian queen Nefertiti and her sister.

In these diptychs, American conceptual artist Lorraine O’Grady connected a personal story — her mixed-race heritage — with a larger history spanning millennia.

Such evocative juxtapositions occur often in the art of O’Grady, whose works are in the collections of many leading museums, including the Harvard Art Museums.

O’Grady visited the Art Museums Tuesday night to deliver an M. Victor Leventritt Lecture in collaboration with Harvard’s Carpenter Center for the Visual Arts. The Carpenter Center, located next door to the Harvard Art Museums, has an exhibition through Jan. 10 titled “Lorraine O’Grady: Where Margins Become Centers.” Curated by John R. and Barbara Robinson Family Director James Voorhies, the show samples O’Grady’s works in photography, film, collage, performance, and writing from 1980 to 2012.

In a talk that unfolded like a great dinner table conversation, rich with anecdotes and touches of humor, O’Grady, age 81, voiced elation at having her first solo show in her hometown.

Elegant and trim in a black leather jacket, leggings, and cowboy boots, O’Grady began by showing pictures from her family album. She spoke of being from an “invisible” class of comfortably off, accomplished African-Americans. While rejecting a culture of cotillions in favor of a bohemian lifestyle, O’Grady brought to art a drive “to make the invisible visible.”

A Boston native whose West Indian parents emigrated from Jamaica, O’Grady was in the class of 1955 at Wellesley College. She worked as an intelligence analyst for the U.S. government and then as a translator before turning to the arts.

Despite mainstream success and an elite education, O’Grady, who lives and works in New York City, creates works that explore the experience of an outsider.

With her mixed-race heritage as her lodestone, O’Grady navigates disparate worlds and finds that two images are better than one to reveal and heal rifts. Her diptychs and hybrid images as well as performances create unexpected juxtapositions that challenge boundaries imposed by gender, class, sexuality, culture, and race.

“Most of what interests me is occurring in the in-between spaces,” O’Grady writes in the indispensible brochure that accompanies the Carpenter Center show.

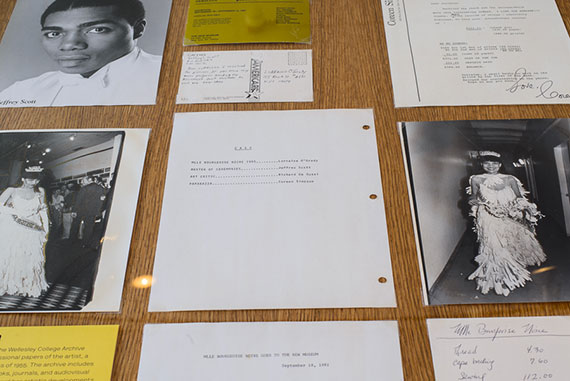

The show’s display cases reward close inspection. A photograph shows O’Grady as her performance persona Mlle. Bourgeoise Noire (1980-83). With sass and style, O’Grady spoofed the look of a high-society debutante to invade New York’s then-segregated black and white art scenes. Wearing a tiara and a white gown made out of 180 pairs of white gloves, she arrived with her own master of ceremonies, art critic, and paparazzi. While shouting her poems of protest, she snapped a white cat-o’-nine-tails, “the whip that made plantations move.”

Documents from the Lorraine O’Grady papers of the Wellesley College Archives show a level of planning fit for a siege, including a step-by-step storyboard. A sympathetic Village Voice article reports her “intervention.”

On the gallery walls at the Carpenter Center are diptychs from the “Miscegenated Family Album” series, in which O’Grady pairs images of her sister and nieces from family photo albums with those of Nefertiti and her daughters. The three pairings show poignant similarities between families separated by millennia. Other works evoke unease. A video, “Landscape (Western Hemisphere),” 2010/2011, focuses on O’Grady’s hair as it churns to the sounds of wind and cawing wildlife. A 1991/2012 diptych, “Body Is the Ground of My Experience (The Clearing: or Cortez and La Malinche, Thomas Jefferson and Sally Hemings, N. and Me),” is a surreal composite of erotic dream and nightmare that alludes to the unacknowledged relationships that created culture in the Western Hemisphere.

Showing an image that is also in the exhibition, O’Grady said, “This is my first self-portrait.” Titled “The Fir-Palm” (1991/2012), the photomontage fuses the branches of a New England fir onto the trunk of a Caribbean palm tree that sprouts from a black woman’s navel.

Advocating hybrids of all kinds, O’Grady concluded by pointing out that Egypt fulfilled its potential as a great civilization by uniting the disparate cultures of the Northern and Southern Kingdoms. “Only when united,” said O’Grady, “did Egypt become itself, a new, fully integrated culture that didn’t see race.”