Q&A with Harvard President Drew Faust

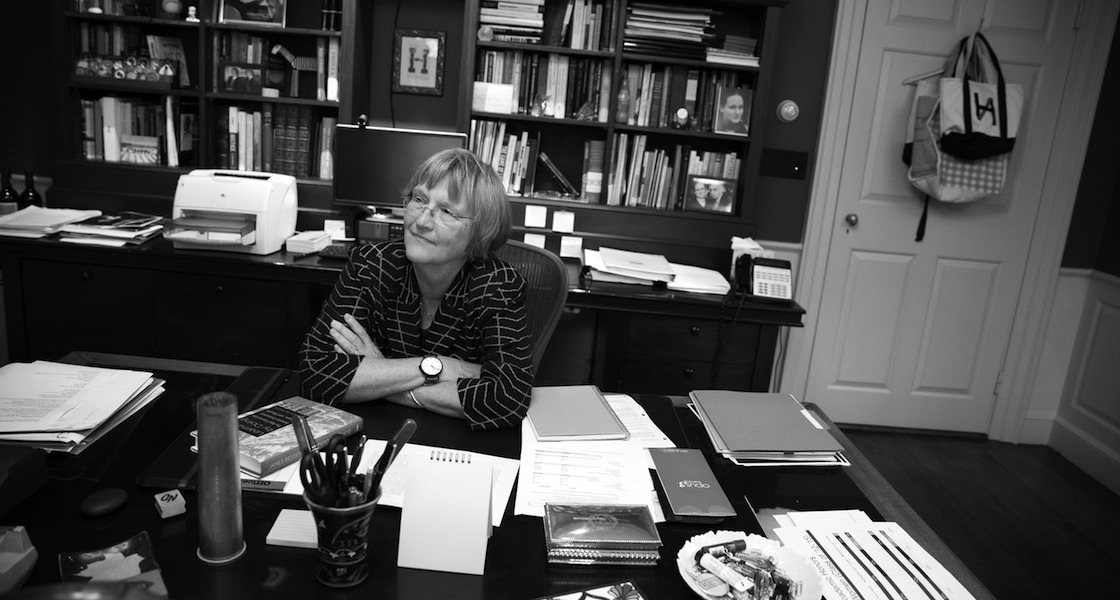

Harvard University President Drew Faust is pictured in her Massachusetts Hall office at Harvard University. Stephanie Mitchell/Harvard Staff Photographer

Stephanie Mitchell, Harvard Staff Photographer

Faust discusses University’s priorities and challenges

Entering her ninth year as the president of Harvard University, Drew Faust has much to celebrate. With two years still to go, The Harvard Campaign has already helped ensure that the College will remain affordable for all students, created new professorships, supported expanded faculty research opportunities, and endowed two Schools, the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health and the Harvard John A. Paulson School of Engineering and Applied Sciences (SEAS).

Harvard’s plans for Allston, which include a new home for SEAS and an Enterprise Research Zone, are steadily moving forward, as is Harvard’s House renewal program that recently unveiled a transformed Dunster House after a 15-month overhaul. Last November, the reimagined Harvard Art Museums opened its doors, and it continues to welcome students and classes as a robust arts teaching and learning lab. And this fall marks the start of an eagerly anticipated Theater, Dance, and Media concentration that will integrate arts even more fully into the life of the University.

But there are challenges ahead, too. Making all students feel “fully included in the Harvard experience” is a top priority in the year to come, said Faust, as are “the issues of sexual assault and safety and full inclusion and participation in Harvard student life for women in the community.” Pushing for more federal funding for science is also at the top of her agenda, Faust said, as is her continued support of the importance of a liberal arts education.

Faust recently sat down with the Harvard Gazette in her Massachusetts Hall office to discuss her priorities and her plans for the coming year at Harvard. She offered up her thoughts on a range of topics, including Harvard’s endowment, the University’s approach to climate change, the continuing importance of the liberal arts and humanities, as well as plans for her next book project and her love for country and western singer Willie Nelson.

GAZETTE: To start, President Faust, could you tell us what you see as your priorities for this year?

FAUST: There are a number of exciting things going on that we want to push forward and pursue. And also a number of challenges.

The [Harvard] Campaign is entering its third year, and we’ve done extremely well so far, but we’d like now to drill down on some areas where we think we need some extra pushing and extra attention. Those include House renewal and financial aid, the Allston science building, and then some extra push for some of the Schools that have gotten slower starts. For example, the Ed School had a brand-new dean when the campaign launched.

As the campaign moves forward, we are also focused on making sure it reaches its goals in terms of what we want it to do for Harvard, such as ensuring access and affordability by supporting financial aid for students, improving the student experience through initiatives like House renewal, and underpinning academic programs, including the type of cross-disciplinary research and teaching that can bring us into the knowledge environment of a 21st-century university. It is less about the dollars than the impact those dollars can have for our students, faculty, and the world.

Allston is another priority that is obviously related to the campaign. We recently received from John Paulson a very exciting gift to endow the School of Engineering and Applied Sciences. As we imagine its presence in Allston and move forward on that building, we see real progress.

There are a number of other aspects of Allston that we’d like to pay attention to this year. One is the enterprise research zone, the 30-plus-acre area that will have business research activity that isn’t necessarily directly sponsored by the University.

The Continuum building, a mixed-use apartments and retail complex at the intersection of North Harvard Street and Western Avenue in Allston, is opening now and has its first residents, and more people are going to be pouring into the area over the weeks and months to come. That will introduce a kind of activity and energy into the neighborhood, and it will be accompanied by additional development in retail and streetscapes.

Then we’re also planning for the next academic venture, thinking about the Gateway building and what academic presence will be there, thinking about the variety of probably quantitatively related activities that will intersect well with the Business School and SEAS. We’re hopeful that a big-data initiative can be moved forward intellectually and also in terms of a physical presence there in the years to come. So Allston is a big area of commitment as well.

I’m also very much looking forward to the launch of the Theater, Dance, and Media concentration, which will embody the goals of the Arts Task Force from eight years ago now. This represents a kind of signal moment for bringing the arts more firmly into the curriculum.

I was thinking about this concentration and chatting with Diane Paulus about it a couple of days ago. She was saying one of her goals is that this be an attractive concentration for people who just love the arts and want to make the arts their lives, but also for students who may not be at all thinking of lives in the arts, but who can learn so much from the kind of collaboration, the kind of creativity, and also the kind of performance and presentation of self that this concentration will nurture and that can be used in so many other areas of professional life and personal life, as well. So that’ll be an exciting development.

GAZETTE: What are some of the biggest challenges?

FAUST: Over the past year or so in particular, with “Black Lives Matter” and “I, Too, Am Harvard,” students have expressed a sense that, although we’ve succeeded in creating a diverse student body, we haven’t done as well in making all of those students feel fully included in the Harvard experience. As I indicated in my Morning Prayers, that’s something that we will be attending to, especially in the context of the lawsuit related to ensure diversity in our student body through our admissions process.

Closely related to this, of course, are the issues of sexual assault and safety and full inclusion and participation in Harvard student life for women in the community. The results of the sexual-conduct survey that was administered last spring will give us some data that will enable the [Harvard] Task Force [on the Prevention of Sexual Assault] to design ways that we can make a difference in combating this terrible problem on our campus and on university campuses across the United States.

I’m also very focused on federal funding for science. This is a time when I think we’ve been getting a little bit more positive response to our arguments for science funding from the Congress for support of federal agencies like the [National Institutes of Health]. So I want to make sure to push that forward, as it is critical to everything we do.

Another area of public concern on which I’ve spoken out quite a bit in recent years might be called the case for college, and particularly the case for the liberal arts. Those are arguments that I hope to advance both here at Harvard as we consider the Gen Ed review in the College, but also in the nation more broadly. We have seen this weekend the inauguration of a college scorecard, which the federal government adopted in lieu of the rankings system that they initially proposed and that I felt was completely at odds with the kinds of goals that we see as essential for college, in that they reduced the purpose of college to a financial outcome.

Although, of course, we wish our students to have successful careers in terms of monetary rewards, we see college as being so much broader than that. I worry that throughout the nation there is a kind of reductionist attitude about college that forgets about the importance of citizenship, of exploration, of creativity, of increased self-knowledge ― all the things that we hope for in the lives that we try to offer our students here. Making those arguments will be an important part of what I try to do in the year to come.

GAZETTE: You mentioned The Harvard Campaign. At last report, we’d already raised something like $5 billion toward the $6.5 billion goal, with two years left to go. Are we going to raise the goal?

FAUST: We are not considering raising the goal at this time, but instead really focusing on the areas of the campaign that must succeed for the campaign to be a success. Those are the things I’ve talked about — Allston, financial aid, House renewal, funding for research and teaching in the humanities and sciences, and the needs of the individual Schools.

GAZETTE: Along those lines, some commentators recently have been critical of the campaign, suggesting that Harvard’s already rich enough, and philanthropists like Mr. Paulson should direct their gifts elsewhere. Others have even gone as far as to say that large endowments should be taxed, should be required to spend money every year. How do you respond to that?

FAUST: I’m always struck by the degree to which many of the commentators lack understanding about how our University finances work, what endowments are and what they do. The point of having an endowment is that it is forever. It is meant to be perpetual. It is meant to fund the activities for which it’s designated over eternity. That means that it is working capital. It earns money to fund those activities each year. But we also have to preserve the corpus of endowment gifts so that they can fund those activities 50 years from now, 500 years from now.

That means we have to be very careful and account for inflation, for example, because it does cost more to fund a professor now than it did 50 years ago. So we have to consider what the endowment can earn in a year, what is the appropriate amount of those earnings to take out in order to fund activities today, and also what percentage of those earnings we should leave in the endowment so that it will be large enough to continue to fund those activities into the future.

Also, Harvard supports more than just students or the College. The endowment funds an art museum whose collection is among the largest in the United States; an arboretum that is an enormous, open public park for the people of Boston; Dumbarton Oaks, in Washington, D.C.; a Renaissance research center in Florence; the largest library system of any university in the world. It even funds a theater, the American Repertory Theater. It’s almost like a coalition of activities that is Harvard.

So when we think about what that endowment is doing, that’s how to think about is it an appropriate size.

Some critics have said we should take 8 percent out of the endowment each year. If we did that, given historic rates of return and what we anticipate in the future, we would erode the principal of the endowment, and the kinds of things that we’re doing now would not be affordable in the future.

Our endowment pays for about 35 percent of the University’s operating budget. That grows to 50 percent in the Faculty of Arts and Sciences. It has enabled us, for example, to fund the extraordinarily generous financial aid that we provide to students in the College. It means that net tuition paid by families has actually gone down in recent years for Harvard students, because we have been able to fund more of that through endowment earnings over the past number of years. Because of the endowment, we’ve been able to award $1.4 billion in financial aid to undergraduates over the past decade.

Were we to eliminate the endowment or lower the endowment or tax the endowment, where would the funding for our activities come from? In all likelihood, it would have to come from the pockets of individual families paying tuition. So it’s an odd thing to argue against endowments, when they are funding so many of the kinds of goals that matter most to the very critics of those endowments.

GAZETTE: Turning to another important topic, can you give us your thoughts on Harvard’s efforts to address sexual assault?

FAUST: It is obviously a very significant problem, as we’ve seen from the concern expressed by our students on campus in recent years. We’ll have a much better way of understanding the dimensions of the problem when the results of the sexual-conduct survey we commissioned last spring are made public. This issue is deeply concerning to all of us and we have done a lot in recent years to address it, but we expect that much more will be needed.

GAZETTE: How should universities address this issue?

FAUST: Considering this as a public-health problem is a helpful way to enable us to understand what effective responses can be, so that is part of the manner in which we’re addressing it.

As you know, the Task Force on the Prevention of Sexual Assault has been meeting now for more than a year. They were really the sponsors of this survey. They’ve made some recommendations that I’ve adopted already in the course of their work ― more and better orientation materials and training, the SHARE website, which provides clearer information about where people can turn if they need help, the doubling of resources at the Office of Sexual Assault Prevention & Response, and the survey itself. This is in addition to the creation of the new University-wide policy and the creation, for instance, of the new office ― the Office [for Sexual and Gender-Based] Dispute Resolution ― to professionally investigate reports of sexual assault.

I anticipate that with the data from the sexual-conduct survey, they’ll be able to make, and will make, further recommendations to me and give me action items. But this must be a high priority for all of us, and it is going to be a very high priority for me in the coming months.

GAZETTE: Provost Alan Garber recently updated the community about health benefits plans for 2016 after plans for 2015 met with some criticism. I wondered how you characterized the administration’s response.

FAUST: We’ve tried to listen very carefully to faculty and staff about their concerns and about the shortcomings they saw in the plans that were proposed last year. The strongest message has been that there is a real desire to have plans in which there’s a completely measurable risk — in other words, where co-insurance and deductibles are not playing a prominent role, and where you may have to pay more in terms of premiums, but you are absolutely in control of what the cost to you might be.

The University Benefits Committee recommended that we design such an option, and so we’ve tried to do that. We’re in an environment where health costs have gone up significantly this year in Massachusetts and are expected to continue to rise, so we have to incorporate that into the new plans. But we have designed different choices so that some of the concerns of those who spoke so loudly last year will be addressed.

There was also a concern about lower-paid employees, and so we have attended to that with more support for individuals at that end of the pay scale.

As a university, we remain committed to providing faculty and staff with high-quality, affordable health care options.

GAZETTE: I know that health benefits is one of the issues under discussion with the Harvard Union of Clerical and Technical Workers as part of their contract negotiations. I wonder if there’s anything you can tell us about those discussions and negotiations.

FAUST: We all depend on — and deeply appreciate — the work that the members of HUCTW do. They have a wonderful tradition here at Harvard in all they’ve contributed to the University. We should all remember that our Christmas vacation is courtesy of HUCTW. That was one of the initiatives that they brought forward, and from which we all benefit enormously. So we’re looking forward to having continued positive interactions with them and with the staff whose work is so critical to the University and all it does.

GAZETTE: I know public service has been a theme for you since you became president of Harvard. Why has it been such an important pillar for you?

FAUST: Public service been an important dimension of my life and things that I’ve wanted to practice and have believed. But I was also very struck when I was named president and started meeting with undergraduates back in the spring of 2007. That was before the financial crisis. They were saying to me that they felt choices outside of financial services were not being offered as clearly to them and not being validated and honored. So I’ve tried to find ways to redress that balance and to show pathways towards public-service careers, and also to underscore how significant those kinds of choices are and how valuable they are for all of us.

A Harvard education and being part of this community in general is such a privilege that we all should think about how we’re going to use that education to serve others. Whatever career choice people make — it could be a public-service career or it could be a private-sector career, but I think everyone’s life should have some element of public service. How do we open that up to people? How do we make them look upon that as an honorable calling, and in some sense a moral imperative? Activities like those that the Mindich family gift is going to enable are an important part of that.

Pursuing a career in public service is highly correlated with having the opportunity to do some sort of significant public service as an undergraduate. So we’ve tried to make that pathway one that students could embark upon.

Public service is a University-wide imperative and tradition. The Law School has a public-service requirement for students. And several of the Schools are almost entirely about public service. Public health and education, for instance, are about serving society. And the Kennedy School clearly is dedicated to public service. “Ask what you can do” is their ethos.

GAZETTE: Climate change was obviously a huge topic last year, with advocates of fossil-fuel divestment protesting here at Massachusetts Hall. Why do you and the Corporation feel that divestment is really the wrong tactic for Harvard? Do you believe the University has a role to play? If so, what is that role?

FAUST: The University has an enormously important role to play in addressing climate change. We educate individuals who can be leaders in advancing the science and the public policies that will help us address this terrible threat. Our faculty produce the kinds of discoveries and policy approaches that will prove both critical and substantive.

In the Engineering School, for example, researchers have been moving forward about how to store solar power better in batteries. Rob Stavins in the Kennedy School has been deeply involved in preparing for the Paris talks on climate change. In the Law School, Jody Freeman has worked on regulation, both at Harvard and in her previous role in the White House.

In addition to teaching and research, we make a contribution as a community by working to reduce our own carbon footprint. Long before some of our peers, we established a climate-change-reduction goal for Harvard’s campus. Since that time, we’ve reduced our emissions by 21 percent.

GAZETTE: What about divestment?

FAUST: I don’t think that divestment is an appropriate tool, because I don’t think the endowment should be used for exerting political pressure. It is meant to fund the wide range of activities that the University undertakes. As we said before, 35 percent of our operating budget comes from the endowment. That is why people gave their funds to create the endowment. It should not be used as a weapon to exert pressure on one group or another.

Many of those advocating divestment from fossil fuels don’t think about the variety of other causes that will be put forward as divestment opportunities. How do we decide as an institution which ones we would see as worthy of our entering the political realm to exert pressure? There’s a terrible slippery slope there.

Universities enjoy many of the privileges that they’re given in our society — tax-free status, for example, other kinds of toleration of enormous amounts of free speech and free expression — because we are seen as not acting in political ways, that it comes from our nonpartisanship, our not committing ourselves to exert political pressure. I worry that if we start using our resources to do that, we open ourselves to all kinds of interventions and political pressures exerted against us, because we have decided to participate in exerting political pressure on issues ourselves.

There are many dangers and it has little effective outcome. What would it mean if we sold our investments? Very little, because there are plenty of other people who will invest in those firms.

I believe it is better to have organizations like Harvard that can exert pressure on those companies as shareholders and say, be accountable to us about how you are going to undertake sustainable investments at a time when your future as a company depends on that. We can use our institutional shareholder status more effectively in that way than by removing ourselves from investment.

GAZETTE: But Harvard has divested in the past, from tobacco, Sudan, and South Africa.

FAUST: Yes, but there is an important difference between those examples and fossil fuels. I believe that when we decide that something is so heinous that we want nothing to do with it ― we wish to withdraw, not to be connected to it — that is a time when it’s appropriate for us to remove our investments from such activities. That was the case in Sudan. That is the case with tobacco. It certainly isn’t the case with fossil fuels that we use every day to come to campus, to travel, to light and heat our buildings.

GAZETTE: Last year, you presided over the reopening of the Harvard Art Museums. This fall, you’ll take part in the launch of the new concentration in Theater, Dance, and Media. At a time when society is ever more focused on providing students with particular skills to compete in the job market, why are the arts and humanities still such a focus for you as president?

FAUST: First of all, they are an essential part of being human, and universities are about more than vocational training. They’re about nurturing the heritage of humankind and sharing it with future generations. That’s just a part of our essential mission.

On a purely practical level, the study of the humanities prepares people for the world ahead, providing them with the tools to make discerning judgments. It is about being sophisticated in understanding the uses of language, of visual representation. It is also about creativity, about imagination, about being able to get outside your own little realm of experience and understand what used to be, so you can understand what might be.

You also are in a time when everybody is going to have a global context in which they live and work, whether they do so in Boston or whether they move to the other side of the globe. Having some sense of different cultures, different heritages, different sets of assumptions, different values among the people of the world is key to being able to operate with people who are different from yourself. The arts and humanities enable us to do so much of that, and I think are the key to the kind of human and humane insight that we all need in order to live together effectively.

GAZETTE: On a slightly more personal note, I’m wondering, as a historian, how do you feel the study of history has enriched your life, but also maybe enriched your presidency?

FAUST: It’s been very important to me. I don’t know if I became a historian because I think the way I do, or if I think the way I do because I became a historian. But when someone presents me a problem, I want to know where did it come from, what’s the history of it, how did this originate, what’s the backstory? I always feel that a conflict in the present, an opportunity in the present, is so shaped by where it came from. I operate very much as a historian, recognizing that issues don’t just drop out of the sky.

But also, history is about change. It’s about how change happens, what makes people resist change, what makes people embrace change. Leading an organization is about change. It’s about moving that institution from one place to another place in terms of moving through time, moving through challenges, and understanding change and how it happens is critical to doing that.

GAZETTE: I know you probably don’t have a lot of time to work on book projects, but in the future, when you do have more time, I wondered if there’s anything that’s been nagging at you — any thoughts, any ideas for a future project?

FAUST: When I think about that, I worry about all the books in my field that I haven’t read over the past, really, almost 15 years now, since I got to Radcliffe, though I did finish the death book [“This Republic of Suffering: Death and the American Civil War”] while I was serving as dean. But in my field, the Civil War, something like 125, 150 books come out every year, so I’m really behind.

What appeals to me, and maybe is a partial solution to this, is I wrote a biography early in my career as a historian, and I loved writing biography. So I might return to biography and use the lens of a single life as a means of getting back into a broader literature and follow an individual through some period of time and use that as the education of me, as well as a chance to write some history again.

I have found myself really fascinated in the past year or two with World War I and some of the comparisons with the Civil War. I’ve written a little bit about that, but I don’t know if that’ll go anywhere further.

GAZETTE: I heard you recently met Willie Nelson.

FAUST: Oh, my heart be still! He was fabulous. I’ve been a Willie Nelson fan since I was in graduate school at least. For a while, I was an official member of the Willie Nelson Fan Club. When I moved once, they lost my address, and I never got back on the list. But I had my little membership card. I’ve seen him perform a whole lot of times. So it was such a treat to get to meet him.

GAZETTE: What’s he like in person?

FAUST: I didn’t spend a lot of time with him, but he was just very warm and terrific, and he went out and gave, at age 82, a spectacular performance. It was really fun.