In response to a recent poll that found most adults who played sports when they were younger stopped doing so as they aged, a panel of experts convened at the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health explored how to keep adults in the game.

Photo by Sarah Jones/Wikimedia

Keeping adults in the game

The health benefits for grown-ups who play sports are great; the challenge is getting people to do so as they age

The benefits of staying active as we age are striking. In addition to keeping the body strong, regular exercise can reduce the risk of heart disease, blood pressure, stroke, and some cancers, experts say. It can even improve cognitive function.

But if keeping the body moving is so good for us, why do so many adults who played sports when they were young stop doing so? The reasons, according to a new study, include a lack of time, interest, or access, in addition to health issues. The study also found a clear gender and income gap.

A panel of experts gathered at the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health (HSPH) on Thursday to discuss the findings and explore ways to keep adults in the game.

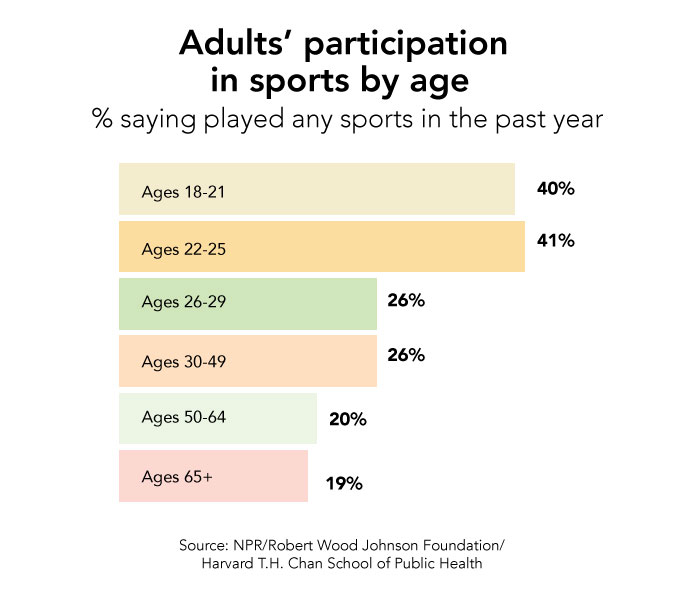

The new poll, conducted by National Public Radio, the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, and the Harvard Chan School, interviewed 2,506 adults over the age of 18. It found that the majority of those who had played sports when they were younger no longer did, with a significant drop-off coming after age 26. (The poll did find that about half of those surveyed said they exercised regularly, including by walking or weightlifting.)

The study revealed that while 40 percent of 18- to 21-year-olds, and 41 percent of 22- to 25-year-olds, play sports, only 26 percent of 26- to 49-year-olds do so, and just 20 percent of adults 50 and over.

Somewhat surprisingly, their own lack of participation did little to quell parents’ enthusiasm for their children’s engagement with sports. In the poll, 89 percent of parents with a middle or high school-aged child said their child benefitted greatly from playing sports, which improves mental and physical health, discipline, dedication, and social skills.

“The poll sums up the question: Is there some way to bridge a gap between the enthusiasm of the power of [sports] for health and other reasons for children, [and getting adults] to carry on after age 26?” said Robert Blendon, the Richard L. Menschel Professor at HSPH and a lead author on the report.

Blendon said about half of the adults surveyed indicated they no longer play sports because of a health problem, a lack of interest, or inconvenience. “So we’ve switched from all the advantages [for] kids,” said Blendon, “to all the disadvantages for me.”

Cobi Jones (photo 2), former Major League Soccer player and member of the U.S. men’s national soccer team, joined via satellite as Ed Foster-Simeon (from left), Elizabeth Matzkin, and Robert Blendon were among the panelists for “Sports and Health: The State of Play in America,” a talk moderated by NPR’s Joe Neel on why participation in sports drops dramatically as people age.

Photos by Craig LaPlante

For panelist Caitlin Cahow ’08, a former member of the U.S. Women’s National Ice Hockey Team and a member of the President’s Council on Fitness, Sports & Nutrition, one way forward is to help young people understand that lessons learned on the field or in the ice rink can offer “tools and skills necessary to succeed in life” beyond the pitch or hockey arena. Encouraging children to embrace a healthy lifestyle, one that includes sports participation and good nutrition as a norm, sets the stage for them to pursue those practices later in life, she said.

“I believe that I truly benefitted from the physical, social, and emotional self-confidence that you get through playing sports,” she said, “and personally I’ve found that to be an incredible advantage as I’ve moved on to face other challenges in my life beyond sports.”

Three factors help explain the report’s findings that men are more than twice as likely as women to say they play sports, according to Elizabeth Matzkin, surgical director of women’s musculoskeletal health and an orthopedic surgeon at Harvard-affiliated Brigham and Women’s Hospital: many older women didn’t have the same access to the range of sports that girls do today; women tend to “put themselves at the bottom of the list” behind the needs of their jobs, their spouses, and their children; and the rising number of overuse injuries in younger and younger children.

“About 3.5 million youths are presented to a physician or an emergency department due to a sports-related injury per year. … Even though we are very good at getting people back to playing, those injuries can lead to problems down the road,” said Matzkin.

She cited tears of the anterior cruciate ligament, or ACL, an injury that is eight times more common in female athletes. A 13-year-old who suffers such a tear, said Matzkin, will likely have arthritis in that knee by the time she hits her 30s.

Educating parents and coaches about the dangers of having a child specialize too early in one sport year-round is an important part of curbing overuse injuries, said Matzkin, and hopefully will lead to women playing sports longer.

“Youth bodies are not meant to specialize at a young age.”

Access to free and safe sports teams and facilities is also important in getting and keeping people of every age involved in sports, said Ed Foster-Simeon, president and CEO of the U.S. Soccer Foundation, soccer’s charitable arm in this country.

Foster-Simeon argued that one reason for the income disparity reported in the poll — which found that lower-wage earners were less than half as likely to play sports than adults with higher incomes — is the lack of free programs and safe places to play in many low-income communities.

Millions of children, he added, “don’t have the opportunity to play.”

He urged the adoption of initiatives like his foundation’s Soccer for Success, a free after-school program in which coaches use small-sided soccer games to help promote healthy lifestyles.

“Coaches are among the most influential people whom children encounter,” he said, and “leveraging that engagement is an opportunity. It’s more than just fun and games.”