Complicated legacy

Scholar explains how views have evolved, and split, on 800-year-old Magna Carta

For centuries Magna Carta, or “The Great Charter,” has been held up as an enduring symbol of freedom and democracy.

It was signed, or more accurately sealed, by England’s King John on June 15, 1215, in a field 20 miles outside London. By all accounts the move was a capitulation, not a heartfelt act of good will. The monarch was pressured into it by barons unhappy with his reign, and in particular with the taxes he levied on them to pay for his disastrous military campaigns in France.

Though initially created to appease only a select few, today the document is considered influential in the establishment of democratic governments and legal systems worldwide — an affirmation that no man, not even a king, is beyond the rule of law. But are the celebrations and the hype surrounding the 800th anniversary warranted? Many scholars argue that the Magna Carta’s importance through the centuries has been greatly exaggerated. Yet for others, its status as a symbol of freedom and a check on absolute power is undeniable.

Elizabeth Papp Kamali ’97, J.D. ’07, sees merit in both arguments.

“When it was first issued in 1215, Magna Carta was really about the 1 percent, to put it in modern parlance,” said Kamali, a scholar of medieval law who will join Harvard Law School in July as an assistant professor. The document largely addressed property rights for “very elite individuals,” she said. One had to dig to find the clauses “we now associate with due process and the things that we value.”

Complicating its legacy is the fact that King John quickly turned to Pope Innocent III to help him revoke the document, which led to civil war. But in the years that followed, the Magna Carta was repeatedly reissued. Though over the centuries it has become distanced from its roots, with large sections removed, “people just kept coming back to it,” said Kamali.

“People came to see it as all about due-process rights and all about limitations on the power of the monarch. Or later, when the American colonies took it up as something important, it was about the limited role of government and the inherent rights of the people.

“And so in that sense, I think Magna Carta has come to represent the importance of the 99 percent vis-à-vis the 1 percent. And for that reason I think, even if the meaning has drifted from its original import, it’s totally appropriate that we make a big fuss.”

The notion of trial by jury is often traced to the charter’s 39th clause. One look at the words and it’s easy to see why. An English translation posted on the British Library’s website reads: “No free man shall be seized or imprisoned, or stripped of his rights and possessions, or outlawed or exiled, or deprived of his standing in any other way, nor will we proceed with force against him, or send others to do so, except by the lawful judgement of his equals or by the law of the land.”

Those foundational principles have not lost their power, said Kamali.

“As a country we are dealing with issues of continuing racial injustice and the problem of mass incarceration. To the extent that Magna Carta calls us back to our first principles — even if, again, it’s at a remove from what the charter was originally about — I think that’s something really valuable.

“If the ‘myth’ of Magna Carta helps bring clarity and urgency to issues of current concern, reminding us of fundamental principles,” she added, “then maybe Bad King John will have inadvertently left a worthwhile legacy.”

The Harvard Law School Library has approximately 30 copies of the document, almost all of which are included in compilations of English statutes dating from around 1300 to 1500.

The Magna Carta turns 800

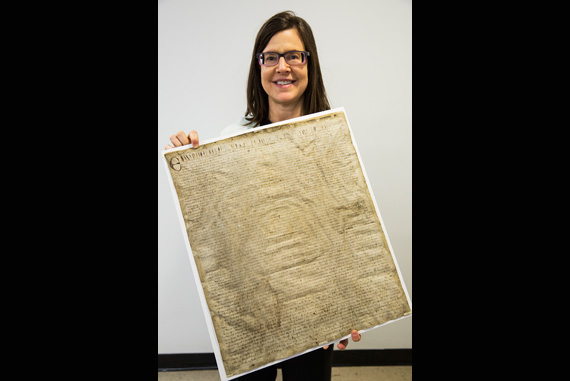

Karen Beck, manager of historical and special collections at the Harvard Law School (HLS) Library, holds a sheriff’s copy of an abbreviated Magna Carta, circa 1327. According to Beck, the document would have been read aloud four times a year in the town square. “This is my favorite Magna Carta of all,” said Beck, “because you can really see how it was used.” The HLS Library has a large collection of manuscript copies of the famous political text, which is celebrating its 800th anniversary. Unlike the sheriff’s copy, most versions of the HLS Magna Cartas are contained in early English statutory compilations dating from about 1300 to 1500. Photos by Jon Chase/Harvard Staff Photographer

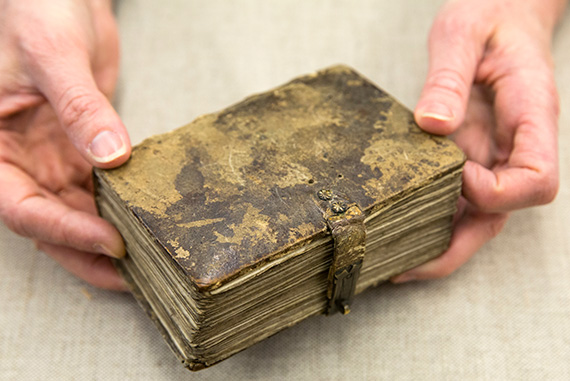

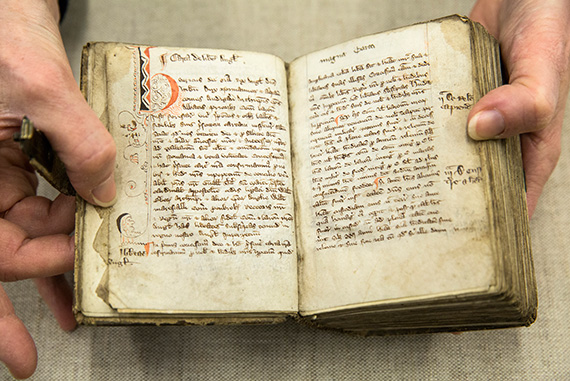

Included in the Harvard Law School Library’s collection are miniature compilations of English statutes such as this one, circa 1300. Only five inches long, this small book begins with the Magna Carta, and would have been typically tucked into a lawyer or judge’s sleeve and carried into court.

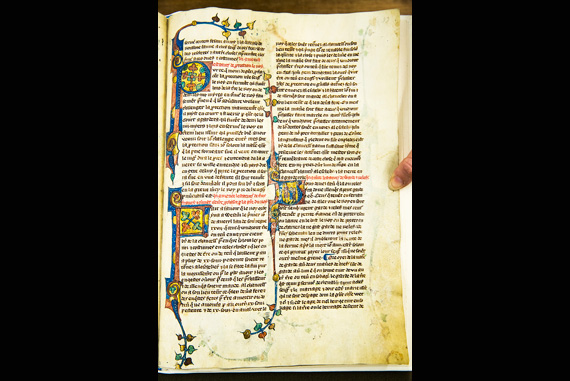

Many of the HLS Library’s statutory manuscript pages are ornately decorated, like this one, circa 1300, which features bright colors, illustrations, and gold leaf embellishments.

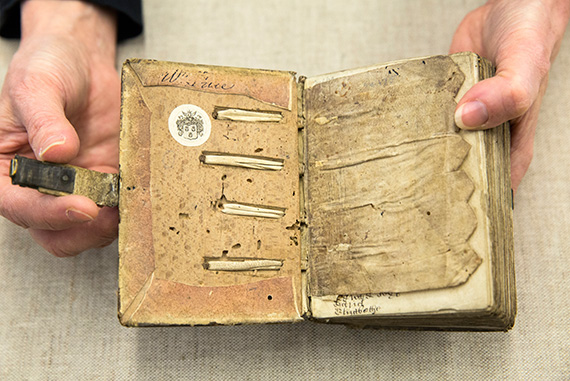

The inside of this small book of English statutes, circa 1300, reveals the intricate original binding.

This small copy of the Magna Carta, circa 1300, is embellished with color and vivid illustrations.

The library is planning an exhibit to coincide with the anniversary and to highlight its copies, which include those found in a small volume only 3.5 inches long, as well as a sheriff’s copy that would have been read aloud yearly in a public square.

Those unable to make it to Cambridge can browse the library’s online material. Early this year staff members completed the digitization of the collection with help from the Ames Foundation, which is also supporting a project to fully describe the contents of the various statutes.

Reflecting on the anniversary, Karen Beck, manager of Historical and Special Collections at the library, said that the best part of working with the rare documents is the chance to bring them to a wider audience.

“For me, the most exciting thing has been to digitize all of these to make them available,” said Beck. “It feels like … a present, a present that we are giving to the world.”