Efforts by Harvard faculty to understand island evolution form the centerpiece of a new exhibition at the Harvard Museum of Natural History. “Islands: Evolving in Isolation” includes specimens from the collections of the Museum of Comparative Zoology, explanatory displays, video of Harvard scientists discussing their work, and living things — lizards, hissing cockroaches, and carnivorous pitcher plants.

Jon Chase/Harvard Staff Photographer

Alone with evolution

HMNH exhibit puts spotlight on islands

What if Darwin’s ship, the Beagle, halted its journey in the Caribbean, well short of the Galapagos’ celebrated finches? Would the father of evolution have found inspiration enough for his theory?

Jonathan Losos, the Monique and Philip Lehner Professor for the Study of Latin America and the curator of herpetology in Harvard’s Museum of Comparative Zoology, thinks so, mainly because the Caribbean has islands of its own. And islands, Losos says, are the great theaters of evolution: Pull up a chair and watch it work.

Efforts by Harvard faculty to understand island evolution form the centerpiece of a new exhibition at the Harvard Museum of Natural History (HMNH). “Islands: Evolving in Isolation” includes specimens from the collections of the Museum of Comparative Zoology (MCZ), explanatory displays, video of Harvard scientists discussing their work, and living things — lizards, hissing cockroaches, and carnivorous pitcher plants.

The MCZ is one of the three research museums that make up the Harvard Museum of Natural History, which itself is one of Harvard’s Museums of Science & Culture (HMSC). Island evolution makes a strong exhibition topic because its theoretical underpinnings can be explained using a range of striking samples from collections, said HMSC Executive Director Jane Pickering.

“One of our goals is always to look at how can we present Harvard research and what’s going on here,” she said. “It’s a major part of our mission.”

Future islands

Kristina Olsen, a visitor from Petaluma, Calif., checks out a display on the pitcher plants of Borneo, part of the new exhibit “Islands: Evolving in Isolation” at the Harvard Museum of Natural History. Photos by Jon Chase/Harvard Staff Photographer

A display of lemurs inside the “Islands” exhibit. More than half of lemurs are found only on the island of Madagascar.

A visitor views the great moa, an extinct bird from New Zealand that stood as high as 12 feet.

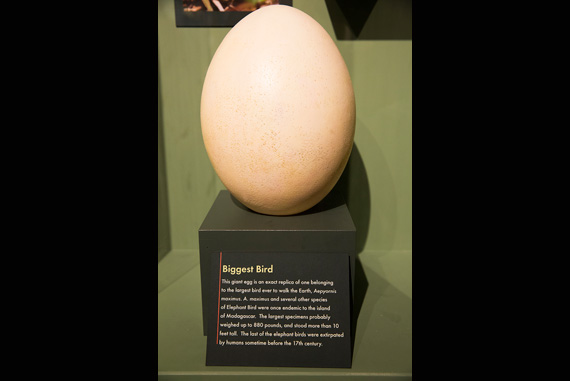

This giant egg is an exact replica of one belonging to the largest bird to walk the Earth, Aepyornis maximus, a species of elephant bird once endemic to Madagascar.

Larissa Lynch and Jackson Petro from Charlotte, N.C., examine a display.

The Komodo dragon is found only on a few Indonesian islands.

Peter Schultz of Virginia Beach, Va., studies the torso of a great moa skeleton, which stands 12 feet high.

The museum has also created a mobile guide, accessible on smartphones, to further enrich the experience, she said.

The exhibition grew out of conversations between Losos and HMNH staff, whose commitment and long hours he cited for bringing it to fruition.

“They deserve the lion’s share of the credit for putting this together,” Losos said. “It blew me away when I actually saw it in person. … There’s just so much to look at.”

Display cases large and small feature Galapagos tortoises, Madagascar’s extinct elephant birds, Australia’s strange egg-laying mammals, platypuses and echidnas, and, not least, the Anolis lizards of the Caribbean, which Losos has spent his career studying.

The reason that islands make such good places to explore evolution is that they’re so simple compared with continents, Losos said. Isolation ensures that only certain kinds of animals — those that can swim, fly, or survive a perilous voyage on floating vegetation — arrive naturally.

Given time, these few species are able to adapt and take advantage of a whole suite of ecological niches — niches filled by different species on the mainland. The result is adaptations such as the bill diversity of Galapagos finches that Darwin studied, the even more dazzling variety of Hawaii’s honeycreepers, the evolution of large bodies and flightlessness in elephant birds and New Zealand’s moas, small bodies in pygmy elephants, and a wide array of other evolutionary solutions to nature’s ecological problems.

Losos said the Anolis lizards are wonderful examples for understanding evolution. Different species have arisen to take advantage of different parts of the forest — from the forest floor and tree trunk to the canopy — highlighting adaptive radiation. Further, distantly related species on different islands have evolved similar solutions to similar problems, illustrating convergent evolution.

Though the insights on broad evolutionary themes are important, so are those produced by islands’ unusual extremes, which demonstrate that evolution in different locations responds to local conditions, sometimes with unexpected results.

“Evolution can produce so many wacky, different outcomes,” Losos said. “Evolution is very opportunistic. What evolves in a particular place depends on local circumstances. Evolution is not a predictable process.”