Researchers have identified a group of neurons in the basal forebrain that help synchronize activity in the cortex, triggering brain waves that are characteristic of consciousness, perception, and attention.

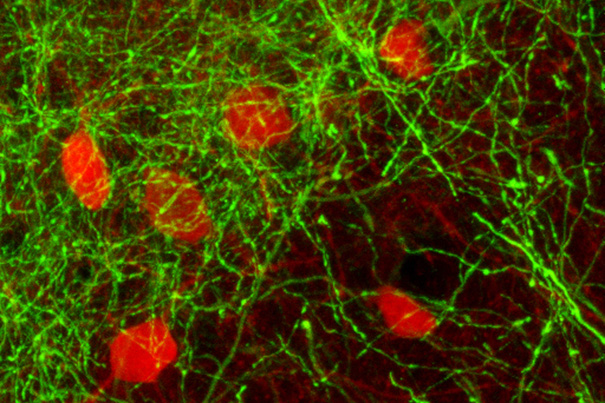

Image by Stephen Thankachan

Tuning in on brain waves

Certain neurons act as conductors, suggesting possible therapies for disorders such as schizophrenia

Like musical sounds, different states of mind are defined by distinct, characteristic waveforms, recognizable frequencies and rhythms in the brain’s electrical field. When the brain is alert and performing complex computations, the cerebral cortex — the wrinkled outer surface of the brain — thrums with cortical band oscillations in the gamma wavelength. In some neurological disorders like schizophrenia, however, these waves are out of tune and the rhythm is out of sync.

New research led by Harvard Medical School (HMS) scientists at the VA Boston Healthcare System (VABHS) has identified a specific class of neurons — basal forebrain GABA parvalbumin neurons, or PV neurons — that trigger these waves, acting as neurological conductors that trigger the cortex to hum rhythmically and in tune. (GABA is gamma-amniobutyric acid, a major neurotransmitter in the brain.)

The results appear this week in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

“This is a move toward a unified theory of consciousness control,” said co-senior author Robert McCarley, HMS professor of psychiatry and head of the Department of Psychiatry at VA Boston Healthcare. “We’ve known that the basal forebrain is important in turning consciousness on and off in sleep and wake, but now we’ve found that these specific cells also play a key role in triggering the synchronized rhythms that characterize conscious thought, perception, and problem-solving.”

McCarley added that understanding the mechanism the brain uses to sync up for coherent, conscious thought may suggest potential therapies for disorders like schizophrenia, in which the brain fails to form these characteristic waves.

“Our brains need a coherence of firing to organize perception and analysis of data from the world around us,” McCarley said. “What we found is that the PV neurons in the basal forebrain fine-tune cognition by putting into motion the oscillations required for higher thinking.”

When they began their investigation, the researchers suspected that the subcortical PV neurons might play a role in regulating cortical gamma band oscillations because they are found in the basal forebrain, an area of the brain that is responsible for switching the brain between waking and sleeping states. While many researchers believed that the cholinergic neurons — another class of neurons located nearby — were the key to the process, McCarley’s team thought that the PV neurons seemed like more likely candidates because they physically reach out toward PV GABA neurons in the cortex.

To test this theory, the researchers needed to be able to selectively activate different types of neurons. Using a technique called optogenetics, in which cells are genetically altered with photosensitive switches, the researchers toggled the PV neurons on and off using laser light.

When the PV neurons were switched on, the cortices of the animals showed more of the gamma activity typical of conscious states. Other experiments were performed to rule out the nearby cholinergic neurons, and to test neuronal firing in vitro. The results showed that PV neurons are necessary to initiate cortical band oscillations, and that they did not rely on other neurons to help trigger synchronized oscillations.

The cortex, where higher-level thinking takes place, is the home of consciousness. If the basal forebrain plays a role in switching the cortex between waking and sleeping states, perhaps the PV neurons play a role in more fine-grained aspects of consciousness.

The chemical that the PV neurons use to transmit their signal, GABA, is a neural inhibitor. When the PV cells fire, they inhibit the PV receptor neurons in the cortex, switching them all off at the same time. A beat later, the neurons in the cortex switch back on, firing all at once. Repeated again and again, this process creates a synchronized, pulsing rhythm, with all of the neurons firing in coordination like musicians playing the same notes in a round over and over again.

McCarley, who has spent much of his clinical career working with patients with schizophrenia, said it was particularly gratifying to be able to bring together his research and his clinical interests, and noted that the study was the result of cross-disciplinary work by a team with expertise in brain anatomy, mathematics, wave theory, and both in vivo and in vitro neurophysiology. Collaborators included co-first authors Tae Kim and Stephen Thankachan, both HMS instructors in psychiatry at the VABHS, and co-senior author Ritchie Brown, HMS assistant professor of psychiatry at the VABHS.