New political science research from Maya Sen (pictured) of the Ash Center at the Harvard Kennedy School and Stanford University’s Adam Bonica quantifies the political makeup of the nation’s judiciary. “The higher or more politically important the court, the more conservative it is, especially when compared to the overall population of attorneys,” the paper concludes.

Photo by Martha Stewart ©

The politics of jurisprudence

Conservatives lead upper ranks of judiciary, and liberals fare better in lower ones, research says

While U.S. Supreme Court opinions are routinely examined through the political lens of the court’s nine justices, far less is known about the ideological makeup of the thousands of judges on the nation’s federal and state benches.

Unlike with politicians, whose views are easily known through public speeches and position papers, voting records, and party affiliations, studying the politics of judges is much more difficult. State and federal codes of judicial conduct prohibit judges from engaging in most political activities or in public discussions of issues or matters that may appear before the court, as a means of preserving an independent judiciary. That stricture limits the data for broad analysis.

Now, research from Maya Sen, an assistant professor of public policy with the Ash Center for Democratic Governance and Innovation at Harvard Kennedy School (HKS), and Adam Bonica, an assistant professor of political science at Stanford University, sheds some light on the opaque world of politics in the judiciary.

Through novel analysis using data from the Martindale-Hubbell (a comprehensive directory of nearly a million lawyers, judges, and law professors) and from Bonica’s Database on Ideology, Money in Politics, and Elections (which scores all individuals and organizations making campaign contributions to state and federal candidates between 1979 and 2012), Sen and Bonica contend in a new working paper that they’re able to measure the politics of judges and attorneys, quantifying what had been known only anecdotally, if at all.

Among the findings:

- Attorneys as a group are “quite liberal” compared with the general U.S. population; judges, on the other hand, are more conservative than lawyers, despite being drawn exclusively from the existing attorney pool.

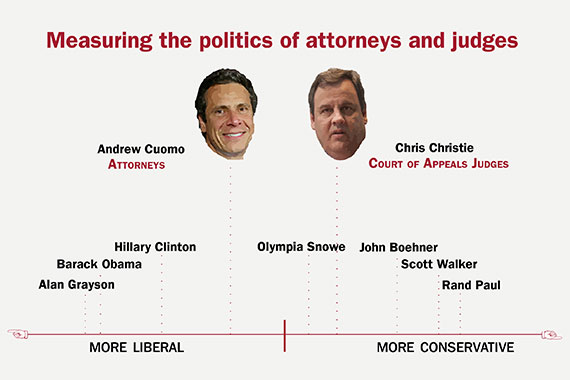

- The median attorney’s politics most closely resemble those of New York Gov. Andrew Cuomo, a center-left Democrat, while the median judge on the U.S. Court of Appeals aligns with a center-right Republican like New Jersey Gov. Chris Christie.

- In lower courts judges skew more liberal, but they trend increasingly conservative up the ranks of the judiciary to state supreme courts and the U.S. Court of Appeals.

“The higher or more politically important the court, the more conservative it is, especially when compared to the overall population of attorneys,” the paper concludes.

“In a world where politics was not part of the equation at all in the selection of judges, judges would look left of center or more left of center than they do now,” said Sen in a phone interview.

This counterintuitive distribution, evident across all federal courts and in about half (24) of all state courts, points to the overarching role that politics plays in the selection process — politicization that largely works to Republican advantage, the paper finds.

“We don’t think that there’s this smoky, backroom thing with people cutting deals and saying, ‘Let’s politicize this court and not this one,’” said Sen. “But what we think is that over time and through many actors pursuing their own interests, that what we’re seeing is a pattern where politics clearly plays a pretty important role in the way that the nation’s judges are selected. And when you look at the big macro level, it appears to prioritize higher courts, more politically important courts.”

So what explains the predominance of conservatives on the elite courts? One factor, Sen said, is that conservative judicial candidates are often “strategically funneled” toward judgeships in the highest courts by politicians and organizations such as the Federalist Society, the influential conservative legal think tank founded in 1982 by law school students at Harvard, Yale, and the University of Chicago.

“The Federalist Society represents a coordinated strategy of retaining and fostering conservative talent at the upper echelons of legal academia — with an eye toward shaping important federal courts — the precise politicization that we consider here,” Sen and Bonica wrote. Their research says that graduates of 14 top law schools who go on to become judges are more conservative than their peers, especially at the levels of federal courts of appeals and state high courts.

Just as politicization is not felt equally across the court system, the level of polarization also ranges, the study says, with the U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals the most polarized and state lower courts the least. Increased politicization of the federal courts, the research says, does lead to increased polarization. Sen said this newly available data to gauge politicization and compare judges across courts has opened new areas for future study around the political patterns of lawyers and law schools, such as who contributes to campaigns and who does not, and why some law schools appear more liberal than others.

Nancy Gertner was appointed to the U.S. District Court for the District of Massachusetts in 1993 by President Bill Clinton. She retired from the bench in 2011 and is now a senior lecturer on law at Harvard Law School (HLS). Gertner said the research “comports” with her view that Republican presidents such George W. Bush selected conservative judges, but Democratic presidents, including Clinton and Barack Obama, J.D. ’91, largely pulled their punches in an effort to sidestep contentious confirmation processes.

“[Clinton] was not about to waste his chits on people who would garner any kind of press, and so his appointments skewed moderate. Obama did the same thing, except the past two years, perhaps,” she said. “That skewing you don’t see with the Republicans. If they’re in position to get someone confirmed, they’re going to get someone confirmed.”

Charles Fried, the Beneficial Professor of Law at HLS, said the research documents what is already known: that politics has always played a decisive role in judicial appointments.

“Presidents regularly nominate judges who are more or less ideologically compatible with them, or in any case, are not ideologically compatible with the people whom they view as their adversaries. That happened with [Franklin] Roosevelt, it happened with Eisenhower except … he miscalculated in the case of [Supreme Court justices] Brennan and Warren … it happened certainly with Kennedy,” he said.

“That’s the Constitution. It’s the president’s nomination. There are states and countries where the judiciary is a kind of career path, a sort of civil service. That has never been our system, not from the first day,” said Fried.

While ideology certainly colors how some judges rule, other factors, like a judge’s legal experience, also play an influential role, said Gertner, who chairs an advisory panel that identifies and recommends candidates for vacancies in the U.S. District Courts in Boston and Springfield to the state’s U.S. senators, Elizabeth Warren and Edward Markey. To help the bench better reflect professional diversity, the panel’s charge from Warren has been to seek out nominees who don’t necessarily come from the usual stable for federal judgeships, like corporate attorneys, federal prosecutors, or lawyers from big downtown firms, said Gertner, a onetime criminal defense attorney.

“When you think about the thousands of decisions that a judge makes — they’re not just decisions about the outcome of a case, but decisions about what matters, how much time to give a case, what’s at the top of the pile, and what’s the bottom — then it makes sense to have people who are going to look at the world differently,” she said.