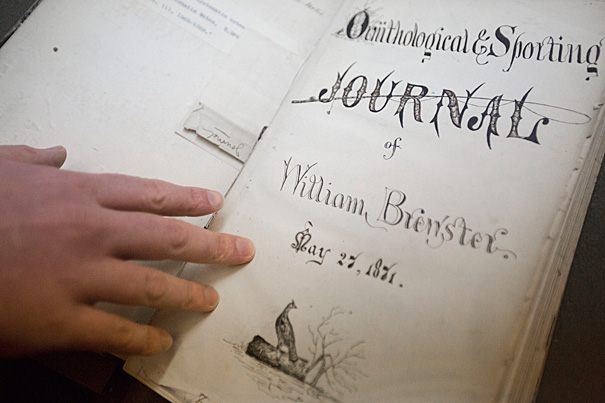

Thousands of pages of diaries and journals by ornithologist William Brewster are being turned into a digital copy that is both searchable and accurate, with the help of Constance Rinaldo (photo 2), a librarian at the Museum of Comparative Zoology’s Ernst Mayr Library, where Brewster’s writings are held.

Kris Snibbe/Harvard Staff Photographer

Crowdsourcing old journals

Project uses Web participation, video games to digitize documents

From the time he was 10 a century and a half ago, William Brewster searched the woods and fields of New England for birds, eventually becoming a noted ornithologist and spending half his life curating the Harvard Museum of Comparative Zoology’s bird collection.

In addition to his passion for fieldwork, Brewster was a diligent note-taker. When he died in 1919, he left behind a collection of 40,000 birds, nests, and eggs, but also thousands of pages of diaries and journals that provide valuable insights on both the birdlife of his era and, through his writing on other subjects, the times themselves.

At least, they would if people could read them.

“In order to look at them, you actually have to come here,” said Constance Rinaldo, a librarian at the Museum of Comparative Zoology’s Ernst Mayr Library, where Brewster’s writings are held. “That makes them, for many people, inaccessible.”

That’s where the video games come in.

The library has embarked on an 18-month collaboration with the Missouri Botanical Garden, Cornell University, the New York Botanical Garden, and the Biodiversity Heritage Library on a project to use crowdsourcing to transcribe Brewster’s journals into a searchable digital format, and to create video games for the more-exacting task of checking those transcriptions for accuracy.

The pilot project, funded by the Institute of Museum and Library Services, aims to help museums and libraries digitize collections of printed materials. Handwritten journals like those kept by Brewster, whose cursive is difficult for optical character-recognition software to translate, is one example; another involves historical documents in hard-to-recognize formats, such as the seed catalogs held by the Missouri Botanical Garden, rich with images, tables, and text in multiple sizes.

The key goal in the initiative is to make a digital copy that is both searchable and accurate, according to Patrick Randall, who is working on the project for the Ernst Mayr Library.

A searchable digital copy can be created by crowdsourcing the transcription to a small army of volunteers, a strategy already employed by several institutions. For this project, Brewster’s journals are being transcribed at two sites, DigiVol and FromThePage. As a step in quality control, each site is creating a copy that can be checked against the other.

The second part, ensuring accuracy, has the potential to be a bit trickier, Randall said. Since poring over a document for errors isn’t everyone’s idea of exciting work, it typically doesn’t attract volunteers; instead, the institute must painstakingly go over the pages.

“The quality control is always the big issue, because ultimately a museum still has to have the final say about what gets the go-ahead, what goes online,” Randall said.

That verification process is critical, Rinaldo said, because not every volunteer is familiar with the subject matter. A lack of familiarity combined with hard-to-read handwriting can lead to errors, such as species names being misspelled, which could cause a search engine to miss entries as researchers gather data.

It may not be critical “if you miss a ‘than’ or an ‘a,’ but if you’re looking for patterns in bird lists and you spell the scientific name wrong, it might not get picked up,” Rinaldo said. “This is primary research. The point is to get primary research out there so people can incorporate it into what they’re doing.”

But what if checking for errors could be made interesting enough for volunteers to do it? Or, better yet, to draw even more volunteers to the task?

Enter TiltFactor, a gaming-focused design studio and research lab led by Dartmouth College Professor of the Digital Humanities Mary Flanagan. The company, which develops games that address educational and societal challenges, has been brought on to develop two video games that will engage volunteers in checking transcribed documents for errors.

“The gaming piece would allow us to ensure the transcripts are close to 100 percent correct,” Rinaldo said.

Flanagan said that although games haven’t been developed for this specific purpose before, the approach itself isn’t unusual, since some kinds of games have been used for social and educational purposes for millennia, a practice she tracked back to the first Olympic Games’ promotion of health and fitness.

First versions of the video games should be ready by early next year, Flanagan said. One is aimed at the more altruistic volunteer, who will want a minimum of gameplay features. The second will have more of those features, such as the ability to track progress, gain points for correct transcriptions, and lose them for incorrect ones.

The challenge, according to Flanagan and TiltFactor game designer Max Seidman, is to create gameplay that is interesting enough to stand by itself and even attract players who might not be interested in natural history, birds, or the broader societal benefit of their high scores.

Video games “are not the first thing you think about when you think of biodiversity heritage,” Flanagan said. “I think this may just be the beginning of ways we use participatory systems in other areas.”