Photographic treasures

Rare photos never seen in the West shared in digital format

A single photograph may capture a moment. A collection can open a window to the past.

Earlier this year, photograph conservators from the State Hermitage Museum in St. Petersburg, Russia, visited Harvard and shared some treasures held by the Hermitage, many never before seen in the West. Recently, they shared several of these images in digital format. These include rediscovered personal photographs of Russia’s doomed royal family and nobility, hidden following the Revolution or “lost” to storage and transfers over the decades.

The Hermitage has embarked on an intense effort to preserve and catalog the more than 500,000 items. “We know that the importance of photographic collections will only improve with time,” said Natalia Avetyan, a curator of photographs from the Hermitage, who was among the group visiting Harvard’s Weissman Preservation Center in April.

Called “The Imperial Collection,” the photos and other materials provide invaluable information about Russian life in the 19th and 20th centuries.

Past preserved in photographs

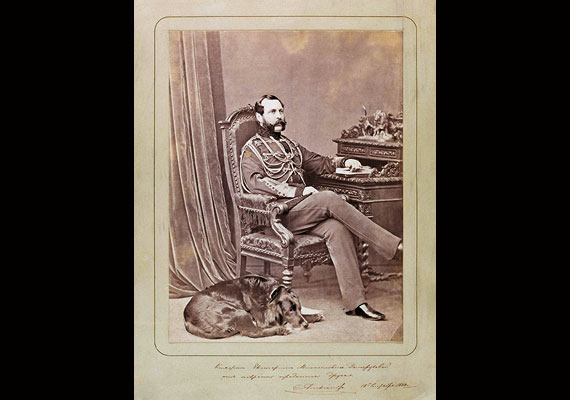

The earliest photograph in the Hermitage’s Imperial Collection is dated 1839; it was a gift to Emperor Nicholas I, who was reportedly fascinated by the new medium. In this 1865 image, his son Alexander II is pictured with his favorite dog in a portrait by pioneering photographer Levitsky Lvovich Sergey. Photos courtesy of the State Hermitage Museum

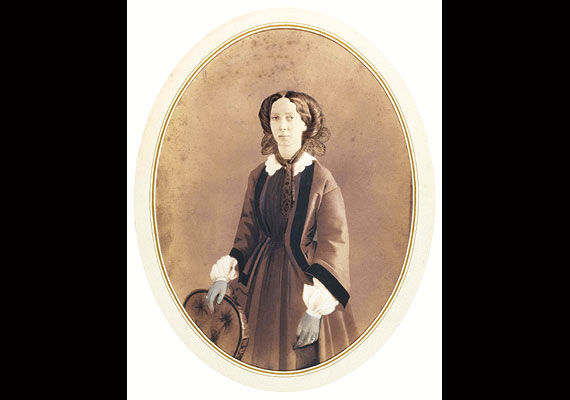

In this 1850s portrait of Empress Maria Alexandrovna, an artist defined the folds of her dress and detail on the chair in a black tint.

Empress Maria Alexandrovna, the wife of Alexander II, was an early photograph enthusiast. This picture of her, taken in the late 1860s, rests in a gilded egg frame.

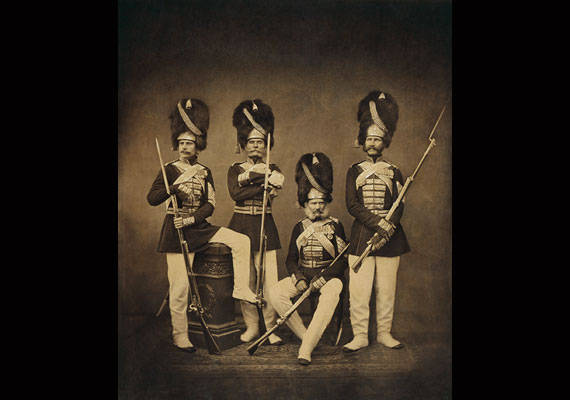

An 1860s portrait of Imperial Palace grenadiers captures the details of their uniforms, and their mustaches.

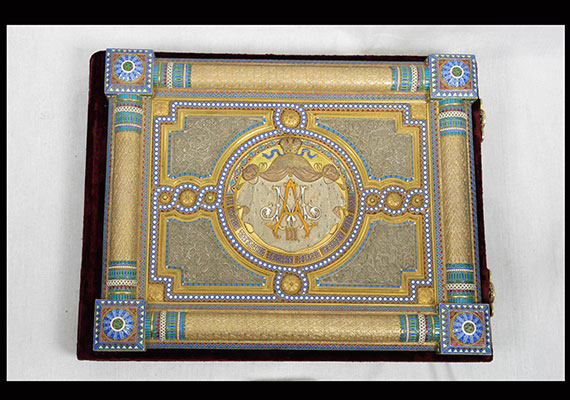

While early albums were quite plain, later covers became objects of art just as beautiful as the photographs they enclosed. This jewelrylike album cover from Alexander III’s collection is gilded and enameled.