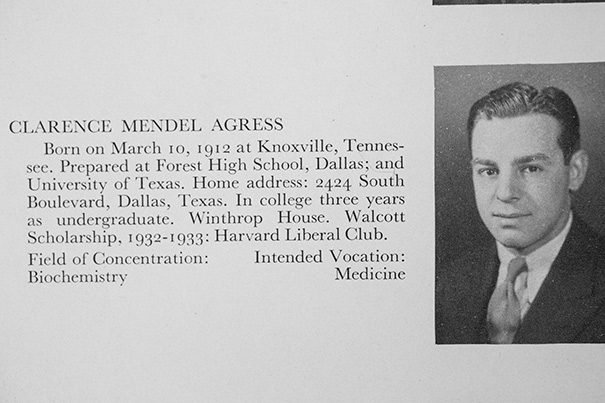

From the yearbook of Clarence Agress, Class of 1933, and his entry in the Harvard Gazette upon graduation. Agress returned to campus for Harvard’s 362nd Commencement and was greeted by his nephew, Allan Miller (right), Class of 1954.

Kris Snibbe/Harvard Staff Photographer

At 101, another look around

Agress ’33 recalls early steps — and pranks — in a life of adventure and accomplishment

Harvard’s first commencing scholars — all nine of them — got their diplomas in 1642. Since then, University-wide, there have been nearly 450,000 graduates. But how many of them were ever attacked by pirates?

At least one: Clarence Mendel Agress ’33, a California cardiologist, researcher, and late-in-life novelist who is now 101. In the early 1950s, off the west coast of Mexico, he and a friend — both amateur yachtsmen — were making a daring, long-distance run to La Paz in a 32-foot Grand Banks powerboat. Bandits waylaid the pair in an area aptly called Pirate’s Cove. “We had to fire a shotgun at them to keep them away,” he said.

Agress’ latest adventure was a visit to Harvard in late May. There were no pirates, unless you include the ones in costume in Harvard Square. But the retired doctor had a big crew with him: about 15 members of his family, representing four generations. Agress was in Cambridge for his first Commencement since late in the Eisenhower administration.

On the day of event itself, May 30, he had a moment of surprise. “I was the only one of the class at the 1933 table.” He had done some research, and figured that something like 11 College graduates from his year were still alive.

Being a 1933 graduate of Harvard College makes Agress one of the last living members of the class that inaugurated Harvard’s House system. Lowell and Dunster opened in 1930 and five others in 1931.

Agress transferred to Harvard after a freshman year at the University of Texas, lived in a boarding house his second year, and by his junior year was one of the first residents of Winthrop House.

Coming back to Harvard wasn’t like motoring across the ocean to La Paz, but Agress still had to get his sea legs. “It looked strange,” he said of his first glimpse of the Yard in more than 50 years. “Maybe it was because of all the furniture and the paved walks. I was really disoriented until I saw the John Harvard Statue.”

He and his family hired a driver and took in the sights of Boston. Of course the tour included points of interest in Harvard’s older corners. Agress looked up Winthrop House, recalling that there had once been an entrance off the street. He remembered the first time his tutor wheeled up to that door on a bicycle. As for nearby Lowell House, Agress said, it “still seemed to be in the right place.”

Lowell House — named after A. Lawrence Lowell, the Harvard president who inspired the House system — reminded Agress of a story more than 80 years old, one that “nobody ever found out about,” he said.

“I played pranks,” he began. In those days, that was helped along by his complete access to the Harvard tunnel system. (He was studying a subterranean insect.) On the night of a formal dance at Lowell House, Agress bought a pig in Boston, greased it up in Cambridge, and set it loose in Lowell. “What a commotion that caused,” he said. Afterward, Agress returned to Winthrop, put on a suit, and went to the dance.

He was never fingered for the greased-pig caper, but nevertheless acquired a covert reputation for mischief-making. Later, when a cow got pushed into the Lowell bell tower, all eyes were on the future doctor. (Let history note: Clarence Agress was not responsible for that one.)

The years Agress spent at Harvard were eventful principally because of the new House system. But there were smaller, near-forgotten moments of history. The first “smoker” — official party — for the class, in early 1930, involved “music, speeches, cheese-throwing,” according to a Class Album account. During his sophomore year, the Faculty Club was being built, along with the Wigglesworth dormitories. Widener introduced its first turnstiles (for security), regular riots broke out in the subway after hockey games, and a debate flared up over the propriety of adding the names of Harvard’s German World War I dead in Memorial Chapel. (They got a plaque.)

In the spring of Agress’ junior year, a student riot in Harvard Square had to be quelled with tear gas and billy clubs. By the Class’ senior year, house sports were thriving (Agress played golf for Winthrop), and the Harvard Lampoon announced the election of James Bryant Conant as president before the Corporation even knew about it.

Agress went on to be a man of astonishing accomplishments. He served in the China-Burma-India theater for five years in World War II; learned Chinese during his service (he still keeps up); hit the high seas (later co-building a yacht with his friend Walter Matthau); took up the Hammond organ; learned to paint in oils; dabbled in astronomy; wrote “Energetics,” a book on fitness and longevity; and penned a line of novels (he is working on his ninth).

Early in his medical career, Agress decided to both practice and research. Just after the war he helped pioneer the use of radioactive iodine to treat thyroid disease. He later founded the first cardiology unit on the West Coast, invented the first heart catheter, treated Hollywood stars (he won’t say who or how many), devised the world’s first blood test to predict heart attacks, and — to stop far short of saying everything — invented the first injectable enzyme to break up the blood clots that form after a heart attack. (Up to that point, pathologists insisted that all such clots were postmortem.)

Agress is a modest man, but he did say, with pride, “I’ve probably saved more lives than anybody at Harvard.”

One other invention of his was out of this world. During the 1960s, Agress headed a team that devised a heart monitoring system for astronauts. “When [Neil] Armstrong stepped on the moon,” he said of the first landing in 1969, “he was wearing my gadget.”

In the 1980s, Agress was regularly playing golf and tennis and running up and down the hills of Bel Air with his schnauzer, Shana. Today, he still stays fit, and looks it. At Commencement, Agress was on foot in the alumni procession. Ahead of him, from the classes of 1929 and 1930, were two men in wheelchairs.

You never know where memory will go. For Agress, of all the sights at Harvard, only the Charles River seemed the same as 80 years ago. He remembered a winter day when the river had frozen over. “We all went ice skating on this utterly smooth surface,” said Agress. “I never will forget that.”