A crop of new classroom and learning spaces across the University is helping to transform teaching and learning, while serving as important models of collaboration. One such collaboration resulted in Zeega, a software platform and social network devoted to digital storytelling. James Burns (from left), Kara Oehler, and Jesse Shapins are co-founders of the software platform.

Stephanie Mitchell/Harvard Staff Photographer

One Harvard

These days, the watchword at Harvard is collaboration

Harvard College and the University’s graduate Schools, centers, and institutes have long stood tall in their respective fields. Increasingly, though, they also are coming together to share students, programs, and facilities, tapping each other’s singular strengths to thrive in a rapidly interweaving world. As such, they’re becoming a whole that is greater than the sum of its thriving parts.

Examples of the rise of One Harvard abound. At the Harvard Innovation Lab (i-lab) and beyond, the University is fostering a culture of cooperative innovation. The University’s experiments in teaching and learning are beginning to have impact on campus and around the world. Plans are under way to develop and rebuild parts of the campus in both Cambridge and Boston. And Harvard is expanding its international ties, through its overseas centers, its broad-based research, and its recruitment of faculty and students from abroad.

Following is a multifaceted update on how Harvard is thriving through interaction:

The campus sweep of unbridled innovation

What’s new under the sun? The classic answer is: nothing. The sun rises and the sun sets. End of story. But the One Harvard answer is: plenty, even just in this academic year.

Give chemical biologist Xiaoliang Sunney Xie a single human cell, for instance, and he will give you back an entire human genome of three billion base pairs. Take Olenka Polak ’15 to a foreign movie and she will decode the dialogue with myLINGO, her new phone-based translation app.

Innovation is what these two share. The word doesn’t just mean creating something new (that’s “invention”). It doesn’t just mean doing the same thing better (that’s “improvement”). Innovation means adding value to old problems in new ways.

Some innovations at Harvard this year were solo, some came from courses, and some were nurtured in institutions with likely names — the i-lab, for instance, or the Government Innovators Network at the Harvard Kennedy School’s (HKS) Ash Center. Others come from innovation-driven entrepreneurship centers at Harvard Business School (HBS) and the School of Engineering and Applied Sciences (SEAS).

Count on innovation to surprise. Many small-scale, little-known innovations this year displayed almost boundless creativity. A May 3 design and project fair in the Science Center Plaza offered looks at a basketball hoop that keeps score, a laser harp, a mind-controlled car, a one-wheeled, self-balancing electric vehicle, an automatic fish feeder, and a math system for crowdsourcing stock picks. Students there from the popular ES 50 course wore T-shirts that said, “Trust me: I’m almost an electrical engineer.”

The most dramatic example of border-breaking innovation, a One Harvard concept, is the i-lab, which acts as a 10-School engine of interdisciplinary creativity.

“Student entrepreneurs don’t respect academic silos,” Peter Tufano, then a professor at HBS and now at the University of Oxford, said when i-lab opened late in 2011, “but nevertheless often found it hard to connect across school boundaries.” True to its mission, the i-lab already has hosted 265 student teams in its 100-day Venture Residency Program. Close to half the teams investigate health and the sciences, a third concentrate on technology, and the rest point toward social innovation. Yet even these borders are flexible. The i-lab start-up Vaxess Technologies, for instance, employs science to accomplish a social good. Its silk proteins are used to thermo-stabilize and store vaccines for shipment to developing countries.

This spring, the i-lab also reached out to the arts. The Deans’ Cultural Entrepreneurship Challenge linked art-makers with leaders in finance, organization, and social outreach. There were 10 winning teams, one for each dean represented. Among the winners was Midas Touch, which used 3-D technology to make great paintings accessible to the visually impaired.

Two students in this year’s “Design Survivor” course at SEAS created a tear-shaped travel mug that can’t tip over. (They call it Bob.) Two undergraduates in a course called “Design of Usable Interactive Systems” created an apt app for their age bracket: It tracks drinking behavior.

Other Harvard innovations were more speculative, pointing to applications on a farther horizon. Consider Assistant Professor Sharad Ramanathan’s remote-controlled worms, for instance. His team at the Department of Molecular and Cellular Biology used targeted lasers to manipulate neurons in the brains of tiny, transparent C. elegans. Their novel investigation technique not only guided wiggling worms, but may help to unravel how the human nervous system works.

There have been innovations in pedagogy too. This spring, the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences (GSAS) introduced an innovation to make fledgling scholars better communicators. Its inaugural class of Society of Horizons Scholars underwent six weeks of intensive training in presentation skills, from voice to visuals. On May 6 at Sanders Theatre, each participant gave a five-minute TED-style talk explaining his or her research. As academics increasingly engage with other disciplines and with the outside world, said Shigehisa Kuriyama, “The ability to communicate one’s ideas lucidly and crisply is becoming an even more fundamental skill.” Kuriyama is the Reischauer Institute Professor of Cultural History and chair of the Department of East Asian Languages and Civilizations.

Innovative pedagogy was also on the mind of Peter Der Manuelian. Harvard’s Philip J. King Professor of Egyptology uses visualization in the classroom, a tool that teaches by showing 3-D virtual worlds. He can lead students on tours of the Giza Plateau as it was 4,500 years ago, for instance, skimming over pyramids, then plunging into burial chambers. Der Manuelian is a believer in the digital humanities — the intersection of new technology with the venerable disciplines that explore truth, beauty, and goodness. Harvard’s innovation in this realm comes in part from the metaLAB@Harvard, a place for creating, as its mission statement says, “innovative scenarios for the future of knowledge creation and dissemination in the arts and humanities.”

Last fall, metaLAB affiliates created the “Labrary,” a student-designed pop-up space on Mount Auburn Street. On display were artifacts hinting at what libraries of the future might look like. There was a retreat-like, inflatable Mylar tent, a bench that was part boom box, and a one-legged “unsteady stool” to keep the user alert.

Elsewhere, the Digital Public Library of America launched a beta version of its discovery portal in April, opening a free-access digital archive of 2.4 million works. The project, a virtual network of national and local libraries, started two years ago at Harvard’s Berkman Center for Internet and Society, which is itself an innovation machine.

One startling example this year is H2O, an educational exchange platform that — beginning with law school case studies — may transform the 21st century landscape of college textbooks. The center developed the electronic platform for creating, editing, and sharing course materials in collaboration with the Harvard Law School Library. “Our hope,” said Jonathan Zittrain, law professor and center co-founder, “is not to be law-specific.” Offered in sharable electronic form, what he called “an intellectual playlist” could create a flexible universe of online materials that are widely used by universities, and in every discipline.

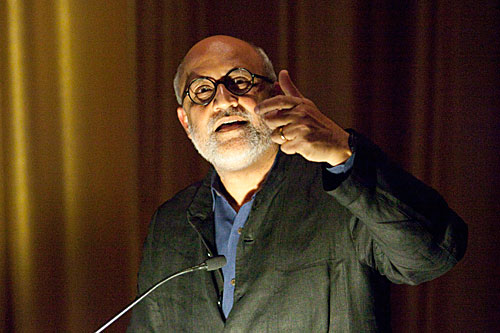

Another Harvard innovation this year was Zeega, a software platform and social network devoted to digital storytelling. Its founders — two recent Harvard Ph.D.s and a 2012-2013 Film Study Center fellow — noticed several years ago that artists, journalists, and Web geeks alike were having trouble harnessing the riches of the Internet. So Zeega, with a click and drag, helps to tame billions of bytes of video, audio, stills, and text.

The result, its creators hope, will be a Facebook-style community of users interested in immersive storytelling, an audience that takes in academics but the world outside too. Co-founder Jesse Shapins Ph.D. ’13, likes to remind listeners that “innovation crosses borders.”

— Corydon Ireland

Making advances in teaching and learning

Perhaps the proverb should be updated for the 21st century: It takes a village to teach a student.

The rapid rise of new technologies, and the race among top universities to harness their potential for transforming higher education, is spawning collaboration across Harvard. Professors, students, information technology specialists, and entrepreneurs are coming together to explore innovative ways to conduct research, to teach, and to learn, virtually and in classrooms.

Programs such as the Harvard Initiative for Learning and Teaching (HILT) — which this year endowed its initial cohort of 47 Hauser Fund grants to professors, students, and staff interested in teaching and learning innovation — and the longstanding Derek Bok Center for Teaching and Learning, which provides a multitude of resources to Harvard’s educators, have given funding and formal recognition to these efforts.

A HILT conference earlier this month drew educators from a variety of disciplines to study the pivotal issue of how to educate from several angles in panels called “The Science of Learning,” “The Art of Teaching,” and “Innovation, Adaptation, Preservation.”

Behind the scenes, the advent of online education has reinvigorated long-running conversations about the fundamentals of teaching and learning, while empowering faculty to teach the way they want, as they go forward.

One recent afternoon, in an unassuming office off Brattle Street, students and fellows were shooting video lectures for HarvardX, the University’s portion of edX, the ambitious experiment to expand access to educational materials online and to help re-imagine the on-campus learning experience. There, Elisa New expounded on the process of creating her first online offering, a module on American poetry that will launch next year on the edX platform.

“I love being part of an experimental start-up project where we figure it out as we go along,” said New, Powell M. Cabot Professor of American Literature, who was spending the day editing her own video lectures about Puritan poetry, shot on location at relevant sites throughout New England. “Had there been a lot of hoops to go through and proposals to write, I’m not sure I would’ve done it. … I think you have to be faster in this world.”

Last May, when Harvard and the Massachusetts Institute of Technology announced their plan to launch edX, both universities’ leaders said they hoped that by exploring how students learn and how professors teach best using virtual tools, edX might also provide important pedagogical insights that could influence the brick-and-mortar college experience to the good.

“We will not only make knowledge more available, we will learn more about learning,” Harvard President Drew Faust said at the time.

A year later, the platform has nearly a million users and offers roughly 50 courses. Earlier this month, edX announced that 15 new university partners — some just down the road (Boston University, Berklee College of Music), others halfway around the globe (Tsinghua University in China, the University of Queensland in Australia) — will join the program.

Beyond the quantitative insights, professors experimenting with new platforms say the process has made them fundamentally rethink their approach to teaching, including in the traditional classroom.

“When faculty teach courses they themselves create, they tend to teach better,” said William Kirby, T.M. Chang Professor of China Studies and Spangler Family Professor of Business Administration at HBS, who is co-teaching a course on China’s past, present, and future. “The very act of engaging in this process is energizing.”

— Katie Koch

Physical changes knit campus community together

Upcoming changes to Harvard’s campus will play a key role in promoting broader collaboration and interaction across the University community. These include further development of Harvard’s land on North Harvard Street and Western Avenue in Allston, a long-term House renewal process, and additional common spaces.

The plan for Harvard’s physical footprint in the coming decades envisions a blended, vibrant campus with the Charles River at its core.

Building and renovation projects near HBS and the athletic fields will bring fresh vitality to the area, including athletic events and other activities at a new basketball arena and a refurbished Harvard Stadium.

The i-lab will continue to drive interdisciplinary discussions and innovation. The Harvard Allston Educational Portal, a program that engages undergraduates and faculty with local residents through a robust series of interactive programs, will foster further learning and connections. And at the crossroads of the campus and community, the Barry’s Corner project will bring 325 new apartments, and retail businesses to the heart of the neighborhood.

“Harvard’s campus, on both sides of the Charles River, supports the academic mission of the University and enables us to develop new spaces for teaching and learning; to create convening and common spaces; to find new and creative ways for our community members to connect with one another; and to enhance our ability to create a welcoming place for students, faculty, staff, alumni, and the community,” said Harvard Executive Vice President Katie Lapp.

A key component of campus development will be the creation of a new science center, the future home for much of SEAS. The center is at the heart of the campus expansion project and will help to transform the area into an innovative hub and a catalyst for learning and teaching.

“Our vision is to create an entire ecosystem that supports new activities and new approaches to learning, research, and collaboration,” said Provost Alan Garber. “We want to develop an area that encourages chance and planned interactions between faculty, students, and entrepreneurs-in-residence, executives, experienced scientists, and alumni. We are also creating an enterprise research zone that will attract businesses that will collaborate with both the Harvard community and the research community in Boston.”

Members of the SEAS faculty are discussing plans for the center and hope to create labs, flexible classrooms, student gathering places, and office spaces modeled after the i-lab, that can be used to develop start-ups, including social ventures, or for “activities where students and faculty can work to take an idea from the lab to the real world,” Garber said.

Garber added that SEAS, with its numerous collaborations with other Harvard Schools and departments, is perfectly poised to unite people from across the University in that endeavor. “We expect there to be a great deal of activity on Western Avenue that combines SEAS with researchers and students from those other fields.”

A crop of new classroom and learning spaces across the University is helping to transform teaching and learning, while serving as important models of collaboration. Pierce Hall was an underused library that was recently converted into a classroom with rolling tables, chairs, and whiteboards. The moveable setup lets students break into groups for project work, and then reconvene for larger classroom discussions.

“It’s their space. They make it their own,” said Eric Mazur, the Balkanski Professor of Physics and Applied Physics. “It’s about taking ownership of their learning.” Mazur helped to develop the classroom, as well a similar learning space taking shape in Quincy House. A resemblant lab/classroom, supported by HILT’s 2012-13 Hauser Grants program, is now in use on the third floor of the Science Center.

“There is a real desire to build more spaces like this and move toward classrooms where there is no longer a central spot for the instructor,” said Mazur. “It should be about the students, and not about the instructor.”

Other classrooms have been outfitted with new technology to help students connect with each other and the world.

The i-lab was designed to foster team-based cooperation and deepen interactions among Harvard students, faculty, entrepreneurs, and the Allston and Greater Boston communities. Two floors atop the i-lab are dedicated to “hives,” flexible, circular classrooms that promote collaboration for the HBS field immersion first-year program.

Near the Radcliffe Quadrangle, Arts@29 Garden is a mix of classrooms and performance spaces. The collaborative arts space supports creativity, collaboration, experimentation, and art-making.

Still, the urge to innovate is hardly new. In 1928, as part of an effort to reduce social and class divisions, Harvard President Abbott Lawrence Lowell created the residential House system. At the time, one report said, students were “on the whole, hostile” to the idea. Today the Houses are cherished and represent the heart of College life.

The 12 buildings contain close-knit, multigenerational communities, with student peers, faculty members and their families, graduate students, and mentors living in buildings designed to encourage and enhance interaction and learning.

The College has begun a long-term effort to renew the undergraduate Houses while preserving their historic character and mission. The renovations will enable students to engage more easily with each other and with the faculty and graduate students living there, as well as to explore their personal and academic passions.

The ambitious initiative began with two test projects, the older, neo-Georgian portion of Quincy House, which broke ground last spring and is scheduled for completion this fall, and McKinlock Hall in Leverett House, on which work begins in June. The changes to Old Quincy include adding elevators, connecting vertical entryways horizontally to allow students to interact across former silo spaces, and a host of environmental upgrades.

Old Quincy will have new seminar rooms, music practice spaces, and a large community room leading to an open terrace that is designed to encourage academic and social events. There also will be strategically located tutor communities to encourage interaction among undergraduates, faculty, and graduate students.

Dunster House will be the first House to be fully renewed, over 15 months beginning in June 2014.

“Twenty years from now, Harvard College’s historic Houses will be at the heart of an expanded University campus. Supported by renewed spaces and nurtured by superlative programs, the House communities will be optimized for a new generation of students, connected more deeply than ever before into the life of this research University,” said Dean Michael D. Smith of the Faculty of Arts and Sciences (FAS), who with Harvard College Dean Evelynn M. Hammonds oversees the project. “Renewing the Houses is critical to providing a student experience both deeply tied to cherished tradition and reaching for the future in a way that is unique to Harvard.”

President Faust has long made common spaces on campus a high priority. In 2008, she convened a steering committee of faculty, staff, and students to develop recommendations on creating places that could foster engagement and community.

“We wanted to create places where people from across the University could come together,” said Dean Lizabeth Cohen of the Radcliffe Institute for Advanced Study, who co-chaired the committee with Mohsen Mostafavi, dean of the Harvard Graduate School of Design (GSD).

First came outdoor furniture that revolutionized the way people interacted in the Old Yard. Brightly colored chairs were scattered about the verdant lawn. Passersby quickly took note, and seats. Each spring, the chairs are returned to the Yard, as well as to the plaza outside Memorial Hall. Cohen said the committee identified the plaza next to the Science Center as a vital Harvard crossroads and has helped to transform it into “an extremely flexible gathering space that can be used for a wide range of activities.”

In the warmer months, farmers markets and food trucks dot the plaza. In the winter, a small ice rink is erected. The plaza is also a popular arts venue and regularly hosts concerts and other performances. A recent extensive overhaul of the space brought new trees, fresh paving, and more seating.

“The Porch” at the steps of Memorial Church was dedicated last month as the latest common space. The area now contains tables and chairs where people can meet for lunch, and where the church staff hosts a regular morning coffee for the community.

Officials plan to develop more common spaces to further connect people affiliated with Harvard to each other and to others in the surrounding communities.

— Colleen Walsh

Harvard’s growing global presence in an interwoven world

Harvard has long been a global institution. It has many faculty members and students from other nations, conducts teaching and research in far-flung locations, and offers abundant coursework on foreign languages, cultures, politics, and business, all to help nurture a new generation of international leaders.

While the work of individual faculty members and the programming decisions of departments and Schools remain crucial to Harvard’s global engagement, the University as a whole is increasingly supporting such efforts and fostering new ways of engagement that cross disciplinary boundaries and knit the University’s offshoots together to reach into the world.

In recent years, the University has strengthened both the administrative and physical support it offers to Harvard community members working overseas. In 2006, Harvard established the Office of the Vice Provost for International Affairs, adding a University-wide academic and administrative leader to spearhead international engagement.

Headed by Jorge Dominguez, vice provost for international affairs, the office created the Harvard Worldwide website, which gathers and presents information on the University’s international research activities. The office also led the effort to enable Harvard to have a central location to access visa and passport assistance, an international travel registry, and a registration point for International SOS, an emergency resource for travelers.

The University is also growing physically internationally. Among the 17 overseas offices run by Schools, programs, and centers are five opened since 2002, run by Harvard entities but charged with supporting activities across the campus. The newest is the Mexico and Central America office of the David Rockefeller Center for Latin American Studies, which opened this year in Mexico City. Other University-wide offices are in China, Brazil, Chile, and Greece. Discussions are ongoing for new offices in a handful of other countries, Dominguez said.

In addition, Harvard’s leadership has provided the University with a global voice. Dominguez has traveled to each of Harvard’s offices and has met with officials in dozens of countries. Those trips are in addition to the travel schedule of President Faust, who in March added South Korea and Hong Kong to a list that includes China, Ireland, Chile, Brazil, Japan, South Africa, and India. Faust has consistently expressed a vision of the University as a global institution, graduating students ready to innovate, participate, and lead internationally.

In recent years, the importance of international experience has been emphasized in undergraduate education, and thousands of students have studied, worked, and conducted research overseas.

The President’s Innovation Fund for International Experience provides grants of between $5,000 and $60,000 to support faculty members who are creating courses and international experiences for Harvard undergraduates. The grants, Dominguez said, are also intended to encourage the faculty at graduate and professional Schools to contribute their global perspectives on education.

The results have included a global health “boot camp,” summer internships with the nonprofit Partners In Health (co-founded by Paul Farmer, professor of medicine and Kolokotrones University Professor) to prepare undergraduates for public health projects overseas. Others are a summer human rights internship organized by Jacqueline Bhabha, Jeremiah Smith Jr. Lecturer in Law and professor of the practice of health and human rights, as well as a Cambridge-based international development boot camp designed by HKS Professor Amitabh Chandra.

Today’s complex global challenges often defy solution by a single discipline, so Harvard faculty members are reaching out to each other, organizing multidisciplinary conferences and workshops, and creating cross-School collaborations to examine such issues in greater depth and breadth.

In January, three dozen faculty members, fellows, and students studying urban design, business, public health, medicine, and religion traveled to Allahabad, India, for a week of intensive study of the Kumbh Mela, a Hindu religious festival that occurs every dozen years.

The large, multidisciplinary project grew from the initial desire of GSD Professor Rahul Mehrotra to attend the festival to examine the urban planning that goes into what is essentially a temporary city that provides services to millions of people over six weeks. As interest grew, Mehrotra transferred the project from the GSD to the South Asia Institute, which he felt would be a better home for a project involving many disciplines.

Mehrotra said Harvard’s regional centers, institutes, and initiatives provide a University-wide resource and neutral ground where such efforts can flourish. Some of those, such as the South Asia Institute, the China Fund, and the Harvard Global Health Institute, were established with interfaculty collaboration as part of their mission, Dominguez said.

Harvard’s recent move into online education has also become a global effort. The six Harvard classes offered so far through edX have drawn hundreds of thousands of students from around the world. The classes represent the efforts of several faculties, including public health, law, engineering, and applied sciences, as well as FAS.

EdX’s Harvard offerings will expand further this fall to at least a dozen courses offered by faculty members from seven Schools, according to Robert Lue, faculty director of HarvardX.

“It is one of the guiding principles of HarvardX to represent all of Harvard University,” Lue said. “One of the critical goals is to expand access to the world.”

— Alvin Powell