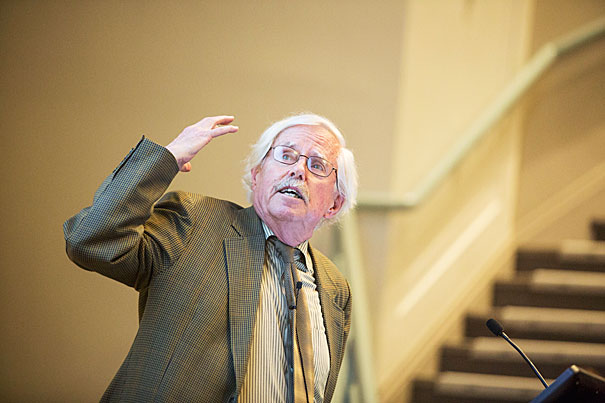

Frances Glessner Lee Professor of Medical Ethics Dan Brock’s Wednesday talk, “The Future of Bioethics,” began with a look at some of today’s central issues — ethical dilemmas arising in clinical and research contexts, matters of confidentiality, stem cells, and neuroethics.

Kris Snibbe/Harvard Staff Photographer

Large-scale ethics

Hard look at ‘who’s responsible?’ in HMS lecture

Dan W. Brock of Harvard Medical School (HMS) on Wednesday delivered the 63rd George W. Gay Lecture in Medical Ethics at the School, focusing on population bioethics.

His talk, “The Future of Bioethics,” began with a look at some of today’s central issues — ethical dilemmas arising in clinical and research contexts, matters of confidentiality, stem cells, and neuroethics. Much of what awaits “will and should include a lot of what went before it,” but a stronger focus on population bioethics is called for, he said.

“Think of ‘bird’s-eye view,’” Brock said — a shift in attention from clinical, individual interactions to whole populations, a “focus on health, not just health care.”

After all, “Health care is responsible for only a minority of longevity gains of the last century,” he said. “It doesn’t have as big of an impact.”

Population bioethics takes into account social factors such as working conditions, class, and exclusion. The “central moral value is social justice,” Brock said. The field has a global focus, drawing on demography, gerontology, genetics, and economic development.

To illustrate this idea, Brock used the example of the Washington, D.C., Metro system. On a ride from the Anacostia neighborhood to the National Institutes of Health in Bethesda, Md., the life expectancy of the population living around the station rises a year for each stop.

“Social determinants largely affect incidence of disease,” he said. “Medical care is imperfect in curing it.”

“What to do?” he asked. “Attack social determinants of health.” Racial discrimination, poverty, violence, and education are all factors.

Brock went deep into the issue of responsibility, the individual’s and society’s. Health problems can be caused by poor diets, lack of exercise, tobacco, and substance abuse, and failure to comply with medical advice. But are “paternalistic bans” such as Mayor Michael Bloomberg’s soda-ban proposal in New York, a solution?

“Many unhealthy behaviors are disproportionately concentrated in the poor,” he said. “Is this a result of personal failing or social injustice?

Brock also delved into the economics of health care. “Cost effectiveness,” he said, “ignores issues of equity.

“Preventive services are systematically devalued,” he continued.

Brock also touched on the “10/90 gap”: Only 10 percent of health investment and research is directed at 90 percent of global disease. That, he explained, is a “huge mismatch between research and the burden of disease in the world.”

“What patterns of health inequality are most morally objectionable? To move forward, we have to know this.

“The poor, not the rich, live near toxic waste dumps,” he said. “The rich can pay to avoid that.”

The distribution of resources tends to favor the elderly due to their greater political power. “Are there ethical principles for just distributions between young and old?”

These broader, population-based issues are “just as important as traditional clinical issues,” Brock said. “The impact is just as great.”

George Washington Gay established the lecture in 1917 with a $1,000 gift to HMS. It is one of the oldest of its kind in the country.