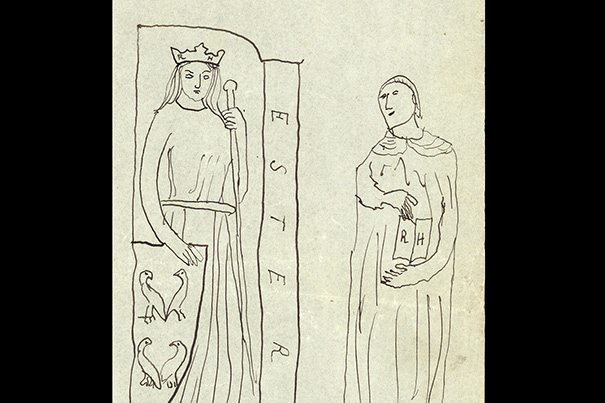

In this drawing, “Esther pour Reynaldo Hahn,” Marcel Proust inscribed Hahn’s initials (RH) on the female figure’s crown and on the pages of the open book. He replaced the caption “Concordia” with the biblical “Esther,” the subject of a 1905 opera by Hahn, and he set her next to her adoptive father “Mordecai,” drawn from a statue of Saint Jerome. Below, Proust wrote that Esther is shown “with little birds,” while Mordecai is “botsched.”

Courtesy of Houghton Library, Harvard University

A remembrance of things Proust

Harvard will devote a semester celebrating Marcel Proust

Marcel Proust, how does Harvard love thee? Let me count the ways: an exhibit of rare letters, now on display at Houghton Library, and, coming later this semester, an online art show, a photography exhibit, a music concert, a film series, and a late-April international conference of literary scholars.

All this affection and attention — a sort of Proust spring at Harvard — is inspired by the 100th anniversary of “Swann’s Way,” the first volume of the novel that grew to be the longest ever written. “In Search of Lost Time” — first known as “Remembrance of Things Past” — eventually filled seven volumes, ranged over 4,000 pages (in the Modern Library edition), and brought to literary life something like 2,000 characters. Its eventual size is partly a memento of World War I, which stalled the French publishing industry, giving the dreamy, discursive Proust more time to write.

For all its length, the plot is simple, said François Proulx, a lecturer in Harvard’s Department of Comparative Literature. “It’s a novel of one man’s apprenticeship as an artist.” “Swann’s Way” is also an artifact of the memories, reflections, and artistic influences that shaped Proust — “the worlds he learns from, and goes beyond,” said the young scholar.

Proulx is co-organizer of “Proust and the Arts,” the April conference, and of the events promised in a related website, which in sum give a sense of all of Proust’s worlds. Proulx is teaching French 165 this semester with co-organizer Christie McDonald, Smith Professor of French Language and Literature and professor of comparative literature. Their class of 22 graduate students and undergraduates will read excerpts amounting to half of “In Search of Lost Time,” which Proulx described as “the Mount Everest of French literature.”

But his long novel does not mean Proust was, as some of his critics said, merely gabby, or a man of leisure whose lazy prose just wandered, as a rich man might from party to party. “That’s unfair,” said Proulx of this common misrepresentation. “He is long-winded, but not rambling.”

To prove it, the young scholar pointed to the centerpiece artifact of “Private Proust” in the Houghton’s Amy Lowell Room: a framed galley proof from the second volume of Proust’s masterpiece, “In the Shadow of Young Girls in Flower” (1919). All around the spliced yellowing pages, painstaking revisions in his tiny hand swarm like bees. Proust wrote and rewrote, said Proulx, with savage attention.

Cambridge is a long way from Paris, where the asthmatic writer composed his magnum opus — largely in pajamas, in bed, and late at night. But Proulx and others have uncovered an unusual share of Proust riches at Harvard, which together illuminate the artist’s life and times and his path to greatness.

For one, there is the rare collection of more than 125 letters given to the Houghton Library in 1994. They are part of the decades-long correspondence Proust had with composer Reynaldo Hahn. When the two met, and became lovers, Proust was 22 and Hahn was 19. That was 1894, and “Swann’s Way” was nearly two decades in the future. The selection of their letters in the Houghton exhibit (up through April 28) are from 1894 to 1912, a period in which Proust made the transition from social butterfly to serious writer.

The Harvard Art Museums also add to our understanding of Proust, whose passion for painting, sculpture, and architecture informed the imaginary worlds he created. This spring, viewers can visit “A Proustian Gallery,” an online exhibit of Harvard-owned examples from 70 of the more than 100 visual artists mentioned in Proust’s works.

All of Proust’s writing, beginning with “Pleasures and Days” (1896), is energetically referential, complete with musical scores, poems, and drawings — a kind of multimedia aesthetic that prevailed in the French literary magazines of his time. In addition, artists and musicians — veiled composites of people he knew — populated his books. “Proust believed in the capital importance of art,” said Proulx, “not just in his own life, but in everyone’s life.”

The science of Proust’s era does not merit the same attention, he added, but the artist had a fascination with new technology, including the motorcar (which he used to tour French cathedrals in 1907), the airplane, and the telephone — devices he tended to describe in mythological terms. At one time the reclusive Proust used a Paris subscription service to listen to live opera over a phone line.

Adding to the contextual riches: Harvard has photographs of Paris at the time Proust was at work, access to films that were derived from his writing, and student musicians who this semester will bring to life the scores either favored by the author or simply part of his pre-war Parisian milieu.

But for now, the Houghton exhibit is the best way to enter Proust’s vanished world. The letters on display show his light, spidery, and well-spaced hand. They reveal his formative relationship with Hahn, to whom Proust read the first 200 pages of “Swann’s Way,” and to whom he often confessed his artistic travail. The letters also reveal the private language the two men used, a sort of sibilant Pig Latin based on adding extra letters to words.

Most surprising, the Houghton exhibit letters reveal little-known drawings that Proust used only in correspondence with Hahn, whom he called “my other self.” One shows a crucifixion scene, in which — Proust’s caption reads — “Christ symbolizes poor sickch Marcel.” In another, Hahn is the Holy Spirit, bearing to the suffering artist gifts of grace and love.

Famously, Proust suffered from asthma and other ailments — and just as famously would often exaggerate his delicacy, wrapping himself in scarves and greatcoats while at table in tony restaurants. Proust kept his living spaces sealed and later in life often felt well enough to write only in the middle of the night, when the air seemed more pure. But his renowned seclusion had an artistic origin, too — the sheer compulsion to write. Around 1909, his desire to complete the book he called cela — “this” — heated to boiling. That same year, he wrote a friend, finishing the work became “a duty.”

It was never a complete seclusion, said Proulx, who is eager to dispel the myth that Proust lived out his final years boxed up in cork-lined rooms. Proust still went out, sometimes scouring the late-night Hotel Ritz for friends. In addition, a voluminous correspondence kept him informed and connected. “They’re his lifeline to the outside world,” said Proulx of the letters. “But they’re also the way to keep the world at bay.”

Proust died in 1922, a quarter century before his beloved Hahn passed away in 1947. The sum of their correspondence is still only partly collected in English editions and not wholly translated into English — a fact that Harvard’s Proust Spring may help change. A small volume of their pivotal correspondence, mused Proulx, “might make an interesting project.”

Meanwhile, the Houghton letters underline Proust’s sense of the serious woven in with the whimsical. One, addressed to Hahn’s dog Zadig, is a meditation on the limits of intellect in artistic creation. Proust avers that rationality was only capable of “weak facsimiles” of the real truth of the human condition. “It is only when I have reverted to the state of dog, to a poor Zadig like you,” Proust wrote, “that I start to write.”

It was something akin to that “state of dog” that Proust touches on in the opening pages of “Swann’s Way,” in a meditation on sleep and dreaming. In deep sleep, “I had only the most rudimentary sense of existence,” he wrote, “such as may lurk and flicker in the depths of an animal’s consciousness.” But then came memory, the primary gift of these near-animal states. Memory, Proust wrote, “would come like a rope let down from heaven to draw me up out of the abyss of not-being.”

Everyone knows that “In Search of Lost Time” is long. But there is one other thing memorialized on that small shelf allotted to Proust in the popular mind: that sudden epiphanies trigger memory, mostly by way of sensory portals such as sound, taste, and touch. The memory of Proust’s childhood village was prompted by the taste of a madeleine dipped in hot tea. The experience triggered, he wrote, “this all-powerful joy.”

The conference on April 19-20 — surely it will be joyful — signifies another Harvard treasure, just as the collections of letters and paintings do: the University’s convening power, needed to muster in one place so many Proust experts, in a year that will be busy with worldwide celebrations of a literary centenary.

During the event, presenters will be confined to a non-Proustian 20 minutes each. Proulx smiled at the idea of this temporal challenge. “We’ll find out,” he said, “if that is feasible.”