Here is a group of officers who have undergone amputations for gunshot injuries, as published in “Photographs of surgical cases and specimens / prepared by direction of the Surgeon General by George A. Otis.”

Courtesy of the Countway Library

Battle cries of freedom

Exhibit shows the horrible human toll that was central to the Civil War

On the fifth floor of Countway Library at Harvard Medical School (HMS) is a wall-high glass case that contains a human femur cracked open by a Minié ball. The Civil War rifle projectile is the size of a bird’s egg. Considered a miracle of ballistics in its day, this conical bullet illustrates the gravity of injuries in a conflict that killed 750,000 Americans, with twice as many dying from disease as from battle.

The exhibit that includes the Minié ball also features letters, photographs, and pamphlets of the era, and is designed to encourage reflection on the injuries from war. Soldiers then, as now, came home with stumps, shell-shattered faces, and lifelong intestinal diseases.

The harsh realities are amply illustrated in “Battle-scarred: Caring for the Sick and Wounded of the Civil War,” open through at least next June. The exhibit officially launched on Thursday with a pair of afternoon lectures at HMS’ Tosteson Medical Education Center. Curating the exhibit was Jack Eckert, with help on some anatomical exhibits from Dominic W. Hall. Both are with Countway’s Center for the History of Medicine.

Harvard President Drew Faust, Lincoln Professor of History in the Faculty of Arts and Sciences, delivered “Civil War and the End of Life,” a look at how the war violated longstanding ideals of death, burial, and grieving. Jeffrey Reznick, chief of the History of Medicine Division at the National Library of Medicine in Maryland, followed with “Disability and the Cultural History of Modern War.” The collection of today’s National Museum of Health and Medicine began in 1862 as the Army Medical Museum. That vast collection exists today, Reznick explained, as “a national monument in its own right.”

Such was the scale of the Civil War, said Faust, that the conflict was “more destructive than all our wars combined.” In first 12 hours of the first battle of the war, at Bull Run, she said, the death toll climbed to half that seen in the entire Mexican-American War a decade before.

The bloody confluence of modern weapons and ancient battle tactics overwhelmed not only the centuries-old culture of grieving, but the standards of medical care, identification, and burial that were weakly mustered to cope with it. Faust said there were no identification tags, no system for notifying next of kin, no infrastructure for graves registration, no ambulance corps, and no war hospitals. (Eventually, in the North, there would be 400.)

At the heart of the exhibit are photographs of the injured, putting faces on the humanity and suffering. One picture shows eight uniformed Union officers, with an array of the blunt nubs left by amputation.

Such explicit photos were not prurient, said Reznick, but were taken for documentary value. Similarly, the specimens collected during the war — gruesome bone fragments included — were “not for curiosities, but data.” He said proof of that came with printing of “The Medical and Surgical History of the War of the Rebellion (1870-1888),” a six-volume, 3,000-page natural history of the war’s toll of injury and disease.

The short-lived Confederacy produced no parallel volumes. But the exhibit does sample the 14 surviving issues of the “Confederate States Medical and Surgical Journal,” published in 1864 and 1865.

Amputations were the war’s signature wounds. The same glass case with the bullet-pierced artifacts includes a shiny bone saw that looks as capable as it was 150 years ago. But soldiers also came home with ailments less visible, disabilities that sound a modern echo. One was called “irritable heart,” a combat-induced anxiety disorder.

The exhibit and its captivating online version open a window onto the culture that grew up around soldiers who returned home without arms or legs, about 70,000 from both sides, by one estimate.

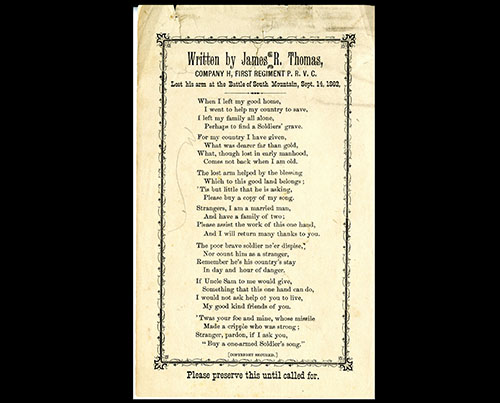

There are examples of the mendicant literature that enabled hobbling and hampered veterans to make a living on the streets by selling pamphlets and broadside poems. “Please buy a copy of my song,” reads one, the work of Pvt. James R. Thomas, who lost an arm at the Battle of South Mountain. “Please assist the work of this one hand, and I will return many thanks to you.”

There are advertisements of the day for artificial limbs. (Between 1861 and 1873, American inventors filed more than 80 patents for such prosthetics, made of wood, cork, rubber, iron, and leather.) The Salem (Mass.) Leg Company produced ads using endorsements from injured soldiers, including one who expected to resume dancing “once winter is over.”

Competition for the prosthetics market was hot. An ad for Douglass Patent Artificial Limbs of Springfield bragged that their “limbs have never been dependent on the Government for their support.” After the war, federal authorities promised prosthetics to every veteran who needed them, prompting the phrase “government legs.” These free limbs were one feature of U.S. government benefaction after the war; another was the country’s first elaborate pension system.

During her lecture, Faust noted that the Civil War not only challenged old paradigms of what made a good death, it also started up the vast machinery of the pension system that transformed the government into an active player in the welfare of its citizens.

One recipient of that support was Philon C. Whidden, M.D. 1866 (1839-1900), one of the faces of war shown in the exhibit. He interrupted his Harvard medical studies to join the Union Army as a private. Wounded at Antietam, Whidden used what he called his “slight medical knowledge” to convince surgeons not to cut off his massively avulsed left leg. But by 1891, after years of increased suffering, he submitted to an amputation below the knee, and the next year applied for an increase to his pension of $24 a month.

Also damaged in the war were the families of soldiers who fretted over their loved ones, often with cause. Even mourning could be difficult, since half of those killed in battle were never identified, Faust said.

The death of Mary Louisa Bodge Glover in 1864 was ascribed to grief, coming a year after her husband, Lt. Alfred R. Glover of Cambridgeport, died in battle. Their pictures appear in the exhibit, along with a leather folder containing Lt. Glover’s portable kit of homeopathic medicines. It looks ready to use.

There also are deft sketches by Massachusetts battle surgeon Lucius M. Sargent, an 1857 graduate of HMS. One drawing of a camp scene in Virginia illustrates a letter to his son, George. Sargent wrote, in what could be a summary of every war, “I have not got anything to love here.”